Over the course of the next few months, many of us at TVOvermind will be participating in our summer rewatch project and reviewing some of our favorite series of all-time that have left a major stamp on television and pop culture in general. One of the shows Hunter Bishop will be taking a look back at is “Mad Men,” which began its run in 2007 and just recently ended last month on AMC.

Welcome to the TVOvermind Mad Men summer rewatch! This will be the first in a series of reviews chronicling maybe my favorite show of all time from the very beginning, and possibly all the way to the very end. Expect these reviews to be a little on the longish side, as I’ll have a lot more time to work on them. I would love to hear from everyone about the show, so please find me on Twitter @Hunter_Bishop or through @TVOvermind. Hopefully, you get as much out of this as I will. Here we go!

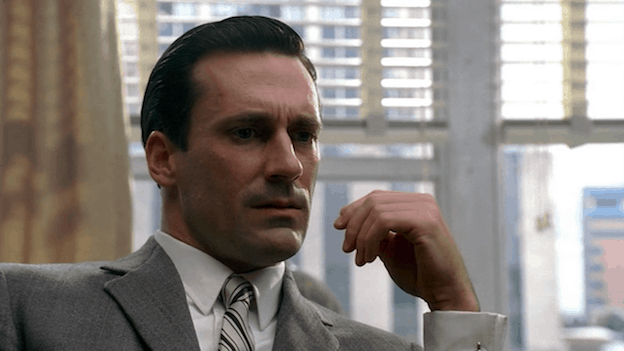

The thing that always strikes me the most about the first episode of Mad Men is how thin Don looks. His face is so much more angular, and he’s so much less broad than I remember him becoming in later seasons. When we see him in 1960, he’s only 33 years old; he’s in his prime as a man, as athletic and healthy as he’ll ever be. Don is already one of the most respected ad men around, working as the Creative Director for a well-respected and well-established company; everyone in the office is more or less in awe of the genius he is. Even his screw-ups lead to things like “It’s Toasted”; even his missteps lead to Rachel Menken.

A thought hit me about halfway through: this first episode is the best it’s ever going to be for Don. He’s on the cusp of ultimate success, and he has everything, and nobody knows who he is. They characterize him as mysterious, but he’s unknown. He has no friends in that office; not even Roger, who is much more of a close colleague/supportive boss than the near-codependent drinking buddy he becomes later on. This is also as good as things are ever going to be with Betty and the kids; they fit perfectly into the life he has constructed, and require nothing more from him than to come home.

* * * * *

Pete Campbell is Pete Campbell from the moment he steps on screen. That inauthentic, slimy ambition drips from him, matching the greasiness of his already-thinning slick-backed hair. His phoniness isn’t really phoniness; he really is who he is on the surface. Pete is always naked about his desires, and that’s what gets him in trouble. He’s like Dustin Hoffman in Rain Man in that way; he can’t help but to just shout out what he’s feeling or act on those feelings. Pete’s triste with Peggy at the end of the episode is an authentic, vulnerable moment, and only he is truly honest about what he’s feeling. To compare him with his forever rival/stepping stone Don: Pete gave up the ghost so that he could have what he wanted, whereas Don was faced with the same sort of opportunity with Rachel Menken and retreated into his shell of masculinity.

But not all of the characters are the same. Ken Cosgrove, in contrast, is the one character in this pilot that is absolutely untenable. His change from lecherous prick to genuine, loving human being is one of the most drastic of the entire series. You forget how much of a jerk he was, and how much he tried to make Peggy feel like an object rather than a real person. The thing that is so frightening about Ken in this pilot is that there is no indication of performance, no moments of naked honesty or frailty or recognition of what he as done. No, Ken is not performing masculinity as much as he is masculinity; he’s not a cog, doing a job, to keep a system running that benefits him. He actually enjoys his behavior, and enjoys seeing Peggy stand stock-still, trying to hide in plain sight as if she were the prey and he the predator. I do not know at what point he changes, or starts to change, but I am desperate to find out.

Joan Holloway is another Ken Cosgrove; she has internalized the misogyny and become one of the boys. She is the first person to tell Peggy to show more skin, and she takes glee in the prostitutional job a secretary must sometimes do. In my first few viewings, it was hard to tell if Joan actually bought into this, or at least what angle she took; after a time, I realized that the joy she got explaining to Peggy the way things work was that she was the one administering the awful truth, and not the one being whipped by it. But Joan is also one of the women of the company, as well. She makes sure that Peggy knows to respect the switchboard, and tells Peggy these things to save her from possibly losing her job and/or getting hurt in a myriad of different ways. Joan isn’t acting, like Pete. Joan believes what she is saying, and that is the most painful thing of all.

* * * * *

There is a way to watch Mad Men that involves engaging with none of the subtext and still coming away fascinated and entertained; this is possibly Matt Weiner’s greatest work. But the richness of the subtext is what elevates the show from enjoyment to a deeper connection. Almost all of this (if not all) subtext has a unifying theme of identity; it’s the line that runs through the scatter plot of things the show discusses. In a practical sense, this is par for the course for a pilot episode; after all, the series ha to build a world that will anchor it for the foreseeable future. But it’s more than that. It’s one thing to discuss identity and another in how you execute that discussion.

Perhaps the most revealing scene to me in the entire episode is the strip club in which Pete, Harry, Ken, and Salvatore go to for Pete’s bachelor party. This scene is essentially a handbook for whom these people are: Ken orders drinks, tells the waitress to come around every fifteen minutes no matter what; Harry one-ups him, saying every five; Pete hits on a woman who sits at the table, tries to feel her up; Salvatore is over the top with his desire to sleep with one of the women, but pseudo-outs himself when his guard isn’t up. Everything you need to know about these people is laid bare in front of you. It’s an amazing snapshot of where they started, especially for Ken and Harry; in terms of who they are to become, they are in separate elevators, going in different directions.

The three characters that are most naked in their desires and feelings are Pete, Don, and Salvatore, and that is utterly fascinating. Rachel Menken is a client, and an important one, and yet Don berates her ideas because she is a woman, stripping her of any agency so that he may, in his mind, retain his. Pete, as hard as tries, cannot be one of the boys. He always returns to the ones in his life he loves, even if he treats them terribly. Salvatore, being a closeted gay man, cannot be who he is, but it’s leaking out all around the edges of his actions. They are all performing masculinity, performing identity that they are not. Those who perform masculinity are those who are the barometers of masculinity; paradoxically, they are the most important figures in removing a patriarchal structure, because only they are being honest. Roger would’ve let Menken say her piece and then given her what she wanted, because he’s more interested in living his life outside of work than he is in fighting with her. Don, on the other hand, must make it known that Don Draper isn’t going to do what he doesn’t want to do, and no woman will tell him otherwise. Don’s honesty leads to a real relationship with Rachel and eventual change, because someone is able to strip (at least partially, at least for a moment) away the shell of manliness in which Dick Whitman became Don Draper.

Why would you not want to engage with Mad Men on that sort of subtextual level, if this is what lies underneath? There is so much more to find and enjoy because of the subtext; if you are watching it for the surface stuff, fine, but you are essentially just getting an interesting workplace drama, and missing out on maybe the most vast and comprehensive character work ever done on television.

* * * * *

The Mad Men pilot is very different from the episodes that follow it, which is a product of the script being written in 1999 and filmed in the mid-2000s. Weiner didn’t totally have a grip on the show yet, but he would very soon. I am incredibly excited to go back and go through these episodes with a critical eye. There is so much to see, and to feel; to watch these characters change will be quite a treat.

This will be very fun.

[Photo via AMC]

Follow Us

Follow Us