For decades now, DC has had an immense advantage over their chief rival, Marvel. Namely, DC – and their movie-making parent company, Warner Bros — had access to the full breadth of DC’s expansive repertoire of heroes whenever they wanted to make a movie based on one of their superheroes.

It’s a fact that most movie-goers accept, but very few of them seem to know exactly why that is. Since 2000, we’ve been trained to understand that the X-Men movies have no bearing on the Spider-Man movies, which have no bearing on the Fantastic Four movies, which have no bearing on the MCU. And although a lot of time has gone into even laymen learning the ins and outs of Marvel’s complicated movie rights, the root cause of it all continues to elude most people.

Turn the clocks back a couple of decades, and the Comic Book industry was going through a tremendous surge of profitability. People who had grown up as childhood fans of superheroes had finally grown into closeted adult fans: fans which comic publishers were fast to discover and eager to exploit as a previously untapped vein of revenue.

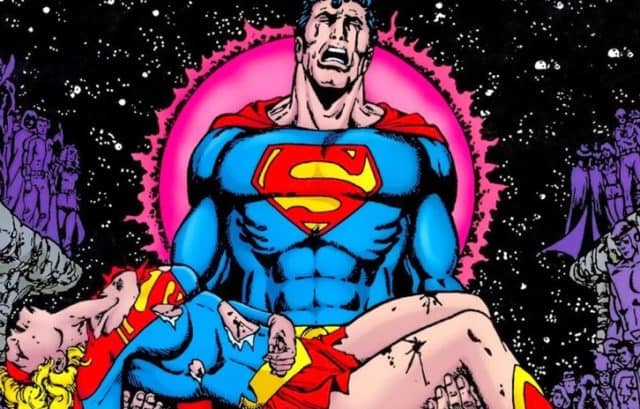

Comics migrated from newsstands and grocery store checkout aisles to increasingly expensive, specialized stores. Because these newly outed adult fans had jobs which afforded them cash to burn on comics, comic publishers began pandering to exactly what these fans wanted to see: big-name characters’ deaths, shocking twists, annualized crossovers, limited-run variant art covers and, my personal favorite, holographic covers. Already popular properties began taking up multiple book lines and notable supporting characters got spun off into their own series.

Eventually, this unsustainable market shifted, collapsing much of the industry. The biggest, most spectacular failure was the bankruptcy of Marvel Comics in 1996. They eventually clawed their way back up to the top of the industry, but at a significant cost.

You see, in order to restock their devastated coffers, they sold off the film rights to many of their most popular characters. But they were a comic publisher, not a film studio, so what were they going to do with those rights anyway, at least at the time? Fox got X-Men and Fantastic Four. Sony got Spider-Man. A few others also made their way out to film studios — like The Incredible Hulk and Daredevil — but these were, for all intents and purposes, the key players.

A funny thing happened in 2008, though: Marvel decided that it wanted to get into the movie game itself. By this point, of course, all of their heavy-hitting, highly marketable headliners had been portioned out to competing studios, enough of which were making good enough returns to keep them there for the time being.

That’s why everything started with Iron Man. I’m sure they would have loved to draw people in with something like X-Men or Spider-Man, but they only had the B-listers to work with. And, by hook or by crook, they started reclaiming all of their outstanding properties. Hulk returned in time for the MCU’s second outing, then Daredevil and even Spider-Man came back after a series of tough (and also incredibly confusing) negotiations: leaving only Fox in the way of Marvel being in DC’s incredibly enviable position of of housing all of their heroes under one roof.

But that’s not really accurate to say about DC now, is it? At least, it’s not any more. Despite owning all the film rights to all of the filmable characters — despite having to worry about nothing more than making good movies from classic comics — they’ve willingly bought into the same problem that Marvel’s been desperately trying to claw their way out from for a solid decade now.

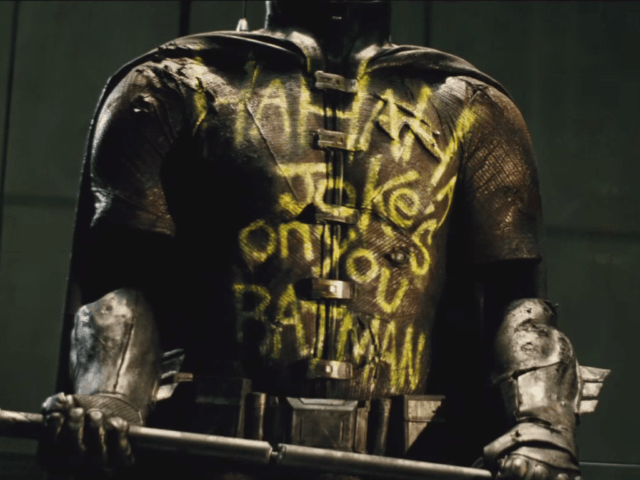

In light of recent hardships — the critical and (arguably) commercial failure of the DCEU, the threat of losing key creative talent, Justice League pretty much being remade from the ground up in a series of last-minute reshoots — Warner brothers has correctly concluded that their current method isn’t working. And while most would have tried correcting their inhospitably dark tone, studio heads breathing over their directors’ shoulders, fast-tracking sequels before filmmakers even understand why the first movie succeeded (or, as is more often the case here, failed) and putting the cart before the horse in terms of designing their shared, cinematic universe, Warner Bros has concluded it’s because the DCEU had too many toys to play with.

Admittedly, it’s easier to manage a few interwoven franchises than it is to juggle all of them simultaneously, and Warner Bros has laid a poor foundation for their franchise plans over the last four years. In fact, there are already rumors of the entire franchise getting rebooted by the newly announced Flashpoint movie. But the root cause of their troubles has always been rushing into production with a bad script, inevitably producing a bad movie to sell to the public: not that their fledgling franchise was locked into too much continuity.

At least with Marvel, you knew by what franchise you were buying into whether it was an MCU movie or not. If you were buying a ticket to see Iron Man or Captain America, it belonged. If you were tuning in to see The Defenders, you were good. If, instead, you wanted Wolverine or Deadpool, it wasn’t. For all of the issues surrounding their film rights, it was relatively simple to know what belonged and what didn’t.

With DC, however, that is not the case. Is The Batman going to be in the DCEU? Matt Reeves doesn’t really seem to sure on that front. Will Gotham City Sirens, the anticipated Harley Quinn-centric movie, feature the same Harley and same Joker as the Harley Quinn / Joker team-up movie? Will either of those be the same versions of the characters from Suicide Squad? What if they recast Ben Affleck’s Batman: is that the same character as before, or a completely new version of Bruce Wayne?

What should be simple questions to answer for any franchise have now become hopelessly confusing for even the most astutely attentive student of the modern-day film industry. But this is what happens when you’re so hopelessly unsure of your own product that you will throw literally anything at the wall, regardless of whether or not it makes any sense, in the hopes that something, somewhere, might finally stick.

Follow Us

Follow Us