Hayao Miyazaki was born in Tokyo on January 5, 1941, amidst the turmoil of World War II. If you’ve seen a whisk of his magic in animated films, you know that this man has no ordinary brain. The inspiration behind his ideas and storytelling is way too complex and beautiful —- and in multiple ways. The veteran animated filmmaker has created wide-acclaimed masterpieces over his five-decade-long career. But the question is, how? Why would anybody create a weird-looking ghost who wants to take a bath in a mysterious hotel? Is it even possible to explain his films to somebody who hasn’t seen his work?

Miyazaki currently has eleven beautiful, complex, and critically acclaimed animated features to his name, and he’s still tirelessly dedicated to what he does best. He also co-founded Studio Ghibli, a name that has now become synonymous with high-profile animated films. This dive we are taking into his work today? It’s about getting to the heart of why he does what he does. Let’s get started.

Hayao Miyazaki’s Films are Inspired By Japanese Folklore and Shinto

The Shinto belief in kami, spirits that inhabit all things, permeates his films. Spirits and gods often interact with humans in his stories, such as in Spirited Away. Miyazaki not only brings kami to life but combines them with a human’s journey. The protagonist, Chihiro, stumbles upon a world where these spirits converge, a place of both awe and intricacy. Not many know this but all of it mirrors traditional Japanese beliefs where the boundary between the human and the divine is fluid and permeable. The bathhouse in Spirited Away serves as a space where gods and spirits come to rejuvenate — reflecting the Shinto practice of purification and reverence for the non-human.

His Animation and Storytelling Touches Themes of Nature, Environmentalism, and Pacifism

Some of Miyazaki’s films, such as Princess Mononoke and My Neighbor Totoro, reflect his deep reverence for nature and his environmental concerns. In Princess Mononoke, he has presented the struggle between the gods of a forest and the humans who deplete its resources — a direct take on the environmental degradation caused by human progress and industrialization. His work also often features idyllic, pastoral settings that are threatened by industrialization or human folly. Miyazaki’s experience of World War II as a child and his general dislike for militarism have influenced his storytelling in Howl’s Moving Castle, which includes anti-war themes.

There Are Flight and Aviation Inspired Characters in His Stories

Miyazaki’s fascination with flight is evident in many of his films, including Kiki’s Delivery Service and Porco Rosso. This interest stems from his family’s business, which manufactured parts for Japanese warplanes during World War II. In Kiki’s Delivery Service, the young witch Kiki takes to the skies on her broomstick, which basically symbolizes her journey to independence and adulthood. Porco Rosso centers around a World War I fighter pilot transformed into a pig — again an incomprehensible brainchild of Miyazaki. Even in Spirited Away — Chihiro flies on the back of Haku — a dragon who soars through the sky. It’s in these meticulous, little details in storytelling and animation that one can truly begin to grasp the depth of Miyazaki’s inspiration.

Literature and His Personal Imagination Play a Huge Role

Miyazaki has created worlds and stories that reflect his philosophies, dreams, and ideas that have been in his brain since childhood. Imagine a random book of hundreds of doodles, give a name and identity to each doodle in the book, and now connect all those doodles with a story that transcends everything you currently know. That’s how his films feel.

But while Miyazaki’s storytelling is clearly deeply personal, his stories often touch on themes from existing books. The Little Prince, for instance, is a Western classic, and it’s his muse for storytelling. The Boy and the Heron, on the other hand, is based on the 1937 book How Do You Live? by Genzaburo Yoshino. The same goes true for most of his other works.

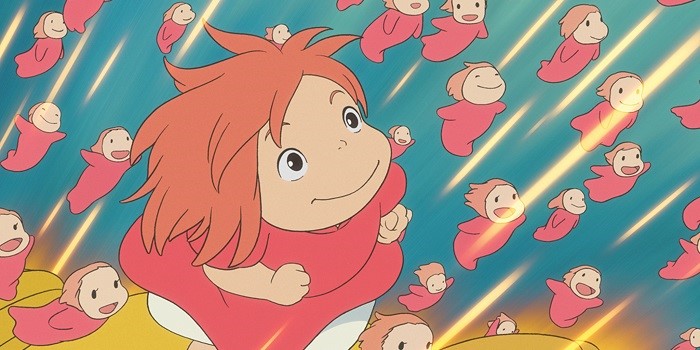

His Stories Are Usually for Children and Have Coming-of-Age Themes

A recurring theme in Miyazaki’s work is coming-of-age stories. Young protagonists usually find their place in the world through adventure and self-discovery in his films. Features like Spirited Away, My Neighbor Totoro, and even the upcoming The Boy and the Heron are good examples of this. Miyazaki holds the conviction that children ought to be encouraged to think with freedom and positivity. After the release of his film Ponyo on the Cliff, Miyazaki actually went on record and said, “We need to liberate our children from nationalism.”

To sum it all up — there is complex and strong reasoning behind Miyazaki’s films. While they may have coming-of-age and comforting themes to impact children for a beautiful and better future, the films are loved by adults equally. They’re out there to be universally cherished. An advice? Don’t try too hard to figure out his exact inspiration as you likely won’t be able to and just enjoy his films.

Follow Us

Follow Us