Few shows have defined the pop culture zeitgeist quite like David Chase’s modern-day, mafia epic The Sopranos (1999-2007), and part of the show’s appeal is that it provided something for every viewing taste. The show was a superb fictionalized exploration of Cosa Nostra during the generational split of the late-1990s, and early to mid-2000s. But any fan of the show will be quick to tell you that the essence of the series was much, much more than a mafia story. Within the series’ 86 episodes, a plethora of themes played out; psychological warfare (a mob boss who suffers panic attacks); the myth of macho masculinity; dysfunctional families, and even symbolic and allegorical displays of existential philosophy. Not to mention, some of the darkest and overt humor that you can ever hope to find in a prestige TV drama. Although the series does offer an easy-to-follow, linear narrative in serialized, story arc fashion, new viewers to the series may find the sometimes slow pacing jarring and off-script. This is normal since we have become accustomed to the age of streaming, where binge-watching a show has taught us to hang onto every cliffhanger spoon fed to us. So with that, just what is The Sopranos really all about?

Organized Crime in the Late 20th and Early 21st Centuries

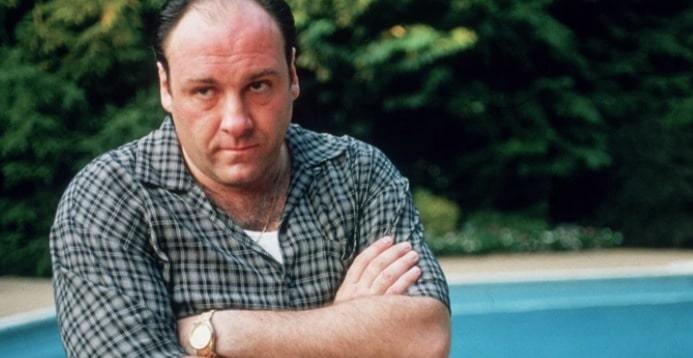

The Sopranos is a series that can best be understood as a “day in the life” structured form of narrative storytelling. Unlike Breaking Bad, for example, the series doesn’t start as a countdown to a protagonists’ inevitable downfall; Tony Soprano’s (the late great James Gandolfini) story is best understood as a wider examination of an American empire in decline. Instead of giving us a corrupt CEO or politician to follow for 6 seasons, Chase chose to create his classic anti-hero as a New Jersey mafia boss. Throughout the series, there aren’t any major plot twists with the main character’s occupation, but rather, the stress Tony experiences as the head of a crime syndicate–with the inevitable prison sentence or execution nearly guaranteed for a boss–defines this part of the series’ plot. Within this story, we are also shown many classic supporting characters that make up Tony’s mafia organization and family. A war between the NYC and New Jersey families breaks out in the final season, but apart from this, most of the mafia component of the series revolves around Tony’s interpersonal relationships with his colleagues.

Psychology

Tony Soprano is the central focus of the series, and throughout six seasons, Chase and his writers unpack a large amount of psychological insight through both the protagonist and the supporting characters. The series begins with Tony visiting a psychiatrist, Dr. Jennifer Melfi (Lorraine Bracco), where he explains his depression and seeks help for his debilitating panic attacks. After being prescribed Prozac, Tony will spend the remainder of the series in therapy, and the scenes we get of these sessions are some of the most insightful and complex across six seasons. Tony speaks of his overbearing mother (Nancy Marchand), who is revealed to be suffering from borderline personality disorder, and frequently imposes a morbid, dark, and claustrophobic mixture of nihilism and despair over her children–and well into Tony’s adulthood. She even conspires to kill her son with his uncle late in the first season, but the hit backfires. Tony’s sociopathic tendencies are also explored throughout the show, including his inability to feel compassion or grief for people, only animals and pets (the ducks, Pie-O-My the horse). Chase and the writers may not have set out to create one of the most insightful TV series ever in terms of abnormal psychology, but they certainly did, and the results are incredible.

Masculinity

A recurring quote of Tony’s throughout the series is that he wishes more guys could be like Gary Cooper–“the strong, silent type.” Masculinity and the need to be emotionless and mechanical is another theme explored in the series. Tony is an ultimate alpha-male; towering, imposing, physically strong, and quick to mock those who find it easier to get in touch with their feelings. His entire mob crew is the same, and there are visceral moments in the series where this shallow existence explodes in violence. One of the more unfortunate examples of this is when Tony, his crew, and the NYC family hurl insults and threats of violence towards the doomed Vito (Joseph R. Gannascoli) simply because it is revealed that he is gay in the final season; he is eventually brutally beaten, mutilated, and killed by the head of the NYC family. Tony refuses to show emotion to his mafia family or even his own family, but we sometimes see him break down in emotional distress during his therapy sessions. Toxic masculinity is not overtly handled in the show, rather, it is up to the viewer to catch the subtext the writers are exploring, which may make those who feel similar cheer–but is always later revealed to be hypocritical as most bigotry usually is.

The Bonds and Dysfunction of Family

Apart from his crime family, Tony’s regular family, and the families of other work associates, are shown to be as real as fiction television gets outside of documentary. Tony’s dour, depressing, and manipulative mother; his flawed hero worship of his deceased father (another hypocritical tough guy and sociopath), his spoiled to the core millennial kids, A.J and Meadow, and his well-meaning, mercurial, yet status and wealth-obsessed wife Carmela (the great Edie Falco) are all just as real and unforgettable as Tony.

Philosophy

Finally, The Sopranos is deeply philosophical, especially the elongated final season. The series can easily be said to be about the finality of death; the precious singularity of life that we take for granted; and even the shallowness and death of organized crime as an institution becoming overloaded with FBI informants and hotheaded drug addicts. When Tony says he “gets it” in the third before last episode, “Kennedy and Heidi,” he could very well mean he gets that life is what it is and nothing ultimately matters–may as well take the midnight train to anywhere.Chase and his writers

Follow Us

Follow Us