In the 1960’s the American wine scene was pretty dim. Wine was largely marketed towards housewives, relegating a millennia-old beverage to one portion of the populace. The following decade came the wine boom of Napa Valley, largely brought on by an exhibition blind tasting in Paris that put California wines on the global stage. Today, with the help of social media and superb (and odd) branding, wine is an everyday commodity for every adult demographic, regardless of social class or economic standing. Like smoking in the old west, wine and alcohol placement in pop culture, music and film generates billions of dollars in revenue for vintners and distillers. It’s predicted that the amount of advertising dollars for alcohol ads will reach $6 billion by 2023, so it’s a given that our beloved wine and spirits will make it into our favorite films as well. Some movies use product placement to create brand awareness through loveable characters on screen, and others use the beverage to establish cultural nuances without including real brands within the wine world. So which ones are fake?

The Fake Wines

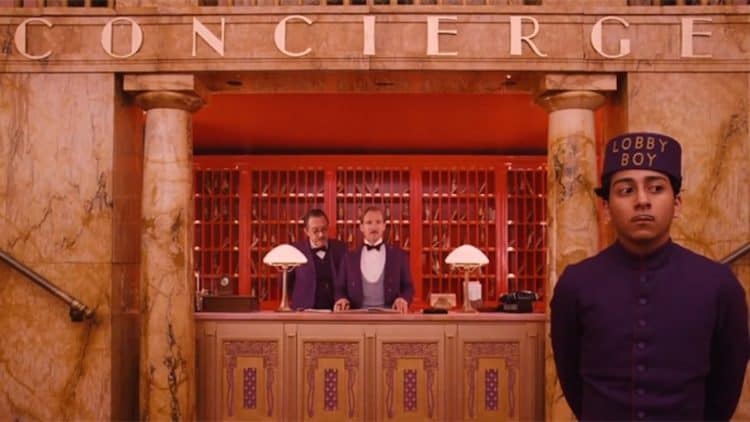

The Grand Budapest Hotel

It wouldn’t be a Wes Anderson film without decadent food and drink, as well as a cast of his perennial favorite actors. The film stars Ralph Fiennes as Gustave H., Tilda Swinton as Madame D., and Tony Revolori as Zero. After the death of Gustave H,’s dear old friend and lover, Madame D., Gustave tells his lobby boy Zero to “Grab a bottle of the Pouilly Jouvet ’26 so we don’t have to drink the cat piss they serve on the dining car.”Pouilly Jouvet is an entirely made-up wine, but is most likely based on a real wine. In the Loire Valley of France, sauvignon blanc is produced to create an aromatic, crisp, wine with hints of stonefruits, the wine is known as Pouilly Fumé. What I believe Gustave H. is referring to when he uses choice language to describe the dining car wine is the sauvignon blanc of the new world— places like New Zealand and the United States, which can often have a slight scent of a boxwood bush, which is a polite way of saying ‘it smells like urine’. What is clever about this artistic choice in naming the wine is that the sophisticated nature of his speaking on the wine is not lost on the viewer because it sounds like a French wine, and not like the 2003 Arrogant Frog, which is an actual bottle of red wine.

A Good Year

This aptly named movie, about as clever as it is good, centers around the story of Max Skinner, played by Russell Crowe. Skinner is a rich broker living in London when he inherits his uncle’s estate in the southern winemaking region of Provence, France. After being suspended from his job for making some unethical choices, skinner makes his way down to France to visit his new estate. The estate, Chateau La Siroque, is a fictional estate creating bad fictional wines. Seriously, part of the premise of the movie is that the wines being produced are awful. This is true until Skinner comes across a bottle of “Le Coin Perdu”, or “The Lost Corner” in the cellar that changes his mind about his inheritance.

As stated, the vineyard and the bad wine in this movie are fictional, however the vineyard where the movie was shot, La Canorgue, is an operating vineyard. The special bottle of that Skinner dug up out of the cellar, “Le Coin Perdu”, was a wine originally developed by the current winemaker’s grandfather, which is still in production today. The wine is a red blend of primarily Syrah from century old vines. This detail, which I hope was planned but I have my reservations, is important in terms of understanding why certain wines are special. Century-old vines generally means that the complexity of the wine is characterized by the life of the vines— that is to say, the wine tastes different because it has survived 100 years, which shows up in the glass. As vines age, they struggle to produce the same amount of fruit that they have in past years—this means lower crop yields. Lower yields translate to more concentrated fruit, which then produces wine that can be aged longer to develop all the nuances and complexities given by its parentage. We aren’t entirely sure why Ridley Scott, who directed the film, made the choice to change the name of the vineyard, but keep the name of the actual vineyards’ keepsake wine, but it makes sense given all the other confusing facets of the film.

The Real Wines

Bottle Shock

As briefly touched on earlier, the 1976 Judgement of Paris tasting endowed California with the clout to compete in the international wine markets of the old world, where they were previously scoffed at. The story of Bottle Shock revolves around one of the American wine producers that was invited to the Paris tasting, Chateau Montelena. Chateau Montelena estate was founded in 1882 by Alfred Tubbs, a beneficiary of the California gold rush. He planted vines, creating a booming wine business for decades until prohibition. The film picks up in the early 1970’s when Steven Spurrier, played by Alan Rickman, visits Napa Valley in search of vintners worth sending to the competition in Paris. Chateau Montelena brings their chardonnay, the wine is barely touched by oak and has the crisp lemon rind nose of that of a French Pouilly Fuissé. The wine, then and now, is a fond expression of some of the finest terroir in the world to grow chardonnay grapes.

There were other American producers that performed well at 1976 Judgement of Paris tasting that were not mentioned in the film, namely Stag’s Leap (not to be confused with Stags’ Leap, a different winery entirely), Ridge Vineyards, and Heitz Wine Cellars, amongst others. These vineyards, which are all still in production today, were not featured in the film because it would have muddied the plot, but also because they are best known for their red wines, and the film is focused on the very finicky chardonnay grape. Bottle Shock, even with its free artistic license to stretch and sell a backstory , represented the events of the Judgement of Paris well. Spurrier (the real-life man) up until his death last March was one of the most influential voices in the wine world, in great thanks to his famous efforts at the ’76 Paris tasting. This film is worth the time it takes to finish a bottle of chardonnay with a friend or date.

Goldfinger

Dom Pérignon Champagne is a name thrown around all over pop culture dating back decades, from rap videos to the James Bond series in the movie Goldfinger. In the film, Bond, played by the dashing Sean Connery and Tilly Masterson, played by Tania Mallet, indulge in a bottle of 1953 Dom Pérignon. Again, the pomp and circumstance that plagues the wine world comes into play in the scene as Bond arrogantly declares that “there are some things that just aren’t done, such as drinking Dom Pérignon ’53 above the temperature of 38 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s as bad as listening to the Beatles without earmuffs!” Aside from the Beatles attack, I hate to agree with the snobby requirements of Bond. Like many other high-end Champagnes like Krug and Perrier Jouët, if the wine is not served ice cold, the wine takes on a yeasty, bready flavor that will leave you wondering why you’ve spent $300+ on a bottle of fermented grape juice.

Another point the film smartly does right is the vintage. Generally speaking, Champagne vintages do not matter as much as flat wine vintages. This is because outside of the crop yield being affected by freeze in the spring, the wines usually vary little from year to year. What 007 got right is the year, 1953. The film was released in 1964 and Dom Pérignon should be drunk no less than 10 years after its bottling. The sweet spot is 10-15 years after bottling for most vintages, and the astute production team showed that they cared for the finer things of the film by including this small detail.Tilda SwintonRidley Scott

Follow Us

Follow Us