If you know anything about basketball (or sports at all), you know who LeBron James is. By my estimation, LeBron James is the best basketball player since Michael Jordan in his prime, and has been the best player in basketball since at least 2008. But he wasn’t really recognized as such (the best player in basketball) until 2009; he spent at least a full year as the best before he was ever recognized as such.

But this year has been different. He’s been a little different, a little less effective, a little less dominant. He has not been the best basketball player in the world this season. But, if you listen to the telecasts and the blogs, you’d never know the difference. LeBron is regarded as the best player even when he isn’t; that is, his reputation precedes him.

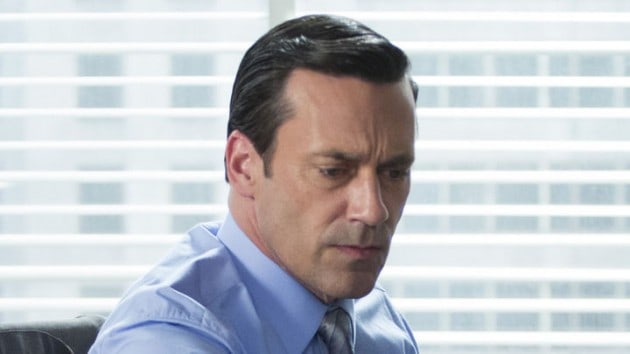

This episode of Mad Men was about Don Draper not being the genius/savant that he’s always been, but it also serves as an interesting meta-commentary on the show itself. Mad Men gets a lot of credit as the best show on air, if not the best show of all time. And, of course, there is a lot of truth to that. But I don’t think that I’m crazy to think that Mad Men hasn’t been the best for a good while. Other shows have usurped it, or have the potential to; we can say with confidence that for the past two seasons it has shown flashes of its brilliance but has been more steady than dominant and more good than great.

Tonight was a flash of that old brilliance; that incredible clarity that comes with a well-structured episode of Mad Men is second-to-none. For the first time this season (and as much as I enjoyed the first two episodes), I actually believed that Mad Men still had some of its old magic left; a few more pitches left in the arm.

We open with Don’s empty apartment; he’s actually moved lawn furniture into the apartment instead of just renting some. He had the carpet cleaned, but not replaced. There is no initiative, as he tries to sell the apartment, to actually make it worth buying. He tells his realtor to use more imagination to help sell the place.

Throughout the episode, we also deal with Peggy and Pete coming to him for advice and the final word on difficult subjects. They both take his word as gospel (he is their boss, of course, but it’s more than that) and trust him to make the right decision. Those interactions lead into the confrontation with Mathis and him calling Don on the carpet for being just “handsome” instead of actually creatively talented.

The apartment storyline ends with the realtor selling Don’s apartment and telling him they just need to “find a place for [him] now.”

All of these interactions and arcs and scenes all point to one idea: Don is pressuring them to sell themselves, or the apartment, or the idea, instead of actually being worth buying, so to speak. He doesn’t care that the apartment looks sad and crappy; he wants to spin a tale about the wonder of the place. He doesn’t actually give good advice to Mathis; just relaying an experience in which Don had success. Don is, as the realtor said, without a place.

The change from actually good to conceptually good is subtle, and most people don’t notice it till it’s too late to do anything about it. Roger, for example: he’s so far past his prime, he couldn’t see if it you gave him a pair of binoculars. He doesn’t actually do any work, but instead pushes it off on his younger and more talented employees. Don, in his own cowardly way, does the same thing. He can’t admit that he has no idea what the future holds but tries to mine his own colleagues for ideas. He doesn’t have anything worth selling, so he must sell the idea of something worth selling.

This is not a problem on the surface; that’s basically what Don has been doing for nearly a decade. But it is when he forgets that’s what he’s doing. The apartment isn’t selling because the realtor isn’t selling hard enough; it’s that the product he gives her is crap, and he doesn’t realize it. Don is no longer an ad man; he’s the ad.

You see it in the conversations with Sally’s friends, too. Don is all flash and good looks and smooth talk; that 17-year-old girl is giving him bedroom eyes, and he knows it. But he’s just spouting platitudes and old wives’ tales and packing them as wisdom. Don is the complete package, twine, and wrapping paper, but there’s nothing inside the box.

Don isn’t the ad man he used to be; he isn’t the guy who could read a room and save the company from certain disaster. He’s barely a mentor. Heck, he’s closer to Lou then he is his old self. At least Lou doesn’t pretend to actually give a crap about his work; he’s out selling his true passion, that stupid comic, and trying to do something about his life. But Don?

No, Don’s content with what he has. He’ll shuffle things around and bring in the patio furniture and wipe down the baseboards. He’ll oversleep and not take a shower and still look fresh as a daisy, but he won’t actually be. At this point in time, Don is selling a product that doesn’t exist. He’s playing musical chairs and trying to keep the chainsaws up in the air as he tries to push through this decline. He’s searching for it within others, instead of trying to find it in himself.

It’s like he told Sally: “You’re a very beautiful girl. It’s up to you to be more than that.”

Stray Thoughts:

– The Joan stuff was really fascinating.

– I’m going to do my best to not be so Don-centric, but all roads lead to Rome, so adjust your expectations.

– Roger and Ted need to work on their drooping mustaches. Though I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Ted looks like a younger Roger; neither of them have any interest in the work, and both push stuff off on to Don.

– Kiernan Shipka is really, really great as Sally.

– Someone on Twitter described Glen as “Neville Longbottom’d” and I’ll be damned if you find a more accurate description for the literally unbelievable transformation he went through.

[Photo via AMC]

Follow Us

Follow Us