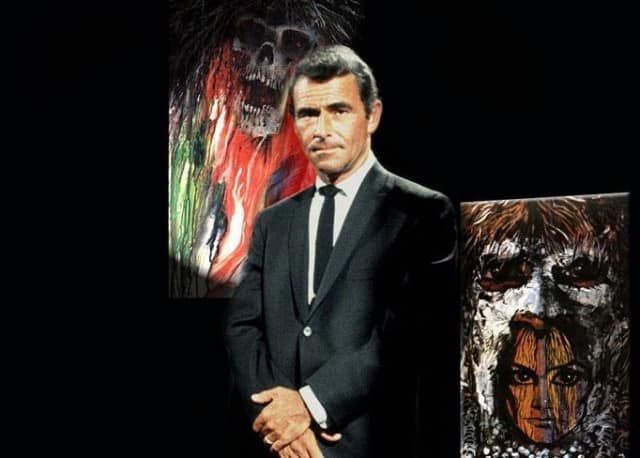

In order to review and tell the story of Rod Serling’s “They’re Tearing Down Tim Riley’s Bar,” I must first eulogize the story of Serling and televison’s first true “Golden Age.”

In his many years in the role of “television’s angry young man,” TV play-write and uber-personality Rod Serling strove for a quality in his own work that was, by and large, severely lacking from his own peers and contemporaries. For every classic produced for this new medium of entertainment and information — “Marty,” “The Long Goodbye,” “The Iceman Cometh” — there were dozens of other lighter, albeit sometimes entertaining, productions that lacked any real social commentary or study of the human condition. Serling believed in his every fiber of being that television had a responsibility to comment on the day to day problems people faced globally: racism, ageism, political corruption, corporate greed and the horror of war. These were but a few of the timeless problems the young writer from Binghamton, New York addressed throughout his career as a writer. He had an edge about him that spoke of an intensity rolled into endless late night writing sessions, cups of late night coffee and a steady stream of deep puffs on filterless cigarettes. The man was an anomaly to the bright glitz of a TV landscape that preached “Father Knows Best,” “Gunsmoke,” and “Leave It to Beaver.” He quickly earned the moniker from people in the world of journalism whose job it was to write about the very craft that Serling practiced, as “television’s angry young man”; the lone voice crying out in a world of homogenization and commercialism.

Of course, the problem with fighting the proverbial good fight is that, sooner or later, you’re going to go down for the count while your opponent stands slightly bruised yet victorious over you. It’s the age old adage of “you can’t fight City Hall”; the game is rigged and you never, ever bet against the mighty and mysterious “House.” But if life is about the inevitability of conformity and the resignation that one person can’t make any real difference, then it must be in the attempt to make change through one’s art that is the deciding factor to a life well lived, futile though it might sometimes appear. Rod Serling never stopped chopping away at the hand of the television industry that fed him, finding ways to make subtle and veiled commentaries in his classic anthology television series, “The Twilight Zone.” But, like his proud, ageing executive on the long ladder down the corporate slope in “Patterns,” the years of fighting and turmoil took a severe toll on Rod Serling, gutting him publically for the edification of the television watching audiences and critics who at one time celebrated him. Like any true writer worth his salt, Serling wrote about this peculiar reversal of fortune subtly at first (“Patterns,” “The Velvet Alley,” “Walking Distance”), and then, finally, much more desperately (“A Stop at Willoughby”). Finally, towards the end of his life, he wrote one final gut-wrenching soliloquy to a world he felt had passed him by: “They’re Tearing Down Tim Riley’s Bar.”

That this unofficial swan song would appear on a television anthology that Rod Serling very publically criticized — “Rod Serling’s Night Gallery” — makes the proceedings doubly poignant. From its very inception, Night Gallery was seen as something of a weak sister to Serling’s demonstrably superior Twilight Zone. Both shows dealt in the realm of the supernatural and science fiction, the difference being that Rod had complete creative control and freedom on Zone. By 1969 however, five years after the Twilight Zone had shuffled off gently into that good night, Serling’s stock was down in the entertainment industry. At the still-young age of forty four, Hollywood viewed him as a dinosaur, a form that had outlived its time and place. Night Gallery belonged to Rod Serling in name only; he was a glorified tenant who the studio felt had just enough currency to sell the show using his name. His scripts were often subjected to brutal editing and the show’s producer, Jack Laird, was the controlling hand of this particular kingdom. The producer and writer frequently clashed and it’s nothing short of a minor miracle that Rod Serling’s commentary on what he felt to be the twilight of his life made it onto the air at all. It was one final grand hurrah for an entire generation of writers such Chayefsky, Schaefer and Frankenheimer and Rod Serling delivered it to a world enmeshed in the Vietnam War, political unrest, campus violence, assassinations and hard drug use on the night of January 20, 1971.

“They’re Tearing Down Tim Riley’s Bar” is about Randolph (“Randy”) Lane, a middle-aged business executive who has reached the end of his tether. He has fought too many fights, lost too many loved ones and seen his own station in the cutthroat world of high-stakes business compromised and trampled upon by vicious up and comers. He drinks too much and he has a deer in the headlights quality as he mourns his late wife and the world they once knew. He’s frantic as he contemplates a world whose rules he cannot comprehend and that has gotten too fast for his own gentlemanly values. He struggles to hold onto the only job he’s known since getting out of the service after the end of World War Two; his eyes reflect those of a drowning man clutching at anything to stay afloat; he seems but one slight facial tic away from bursting into deep, mournful sobs. Then comes the day when he finds out that they’re going to tear down Tim Riley’s bar.

Tim Riley’s bar has long been vacant, but for Randy Lane, it is a sacred place of ghosts and memories; the bar where he would take his late wife for a drink, where his long dead father one time proudly belted out a tin-eared rendition of “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow” for his returning war hero son, where a fellow could feed a dime into the bar nickelodeon and hear three Glen Miller records: It represents a simpler place and time for Randy. So when a sign is put out in front of the old bar proclaiming for 1971 America that it will soon be torn down to make room for an office high rise, some indelible and fragile sliver of a string splinters within Randy Lane and there’s no escaping the reality of a world without one of the last remaining vestiges of his former life. It is, as Randy summarizes it, a “goodbye to Andy Hardy, to rumble seats, saddle shoes and long pre-Pearl Harbor summer nights.”

The ghosts of Tim Riley’s bar and of all of the characters from his past, long gone, begin to insert themselves more profoundly into Lane’s modern day existence. He receives telephone calls from some ethereal 1945; he wanders from a moment in the present into the 1940s hall of the hospital where his wife has died. Time itself seems to bend and fracture under the weight of Randy Lane’s grief and sheer sadness for being in a world he thinks he has no place in. And always, with great relief, he finds himself standing outside — and finally in — Tim Riley’s bar, an oasis for a man who is himself something of a ghost in his antiquated business suit that looks as if it came right off the rack from the 1950s, and his neat haircut, an anomaly if ever there was one as he walks amongst all of the wide lapels, copious fringe, unruly sideburns and ever-widening bellbottoms. He is a man retreating from life and racing back towards a time that was more substantial and more fulfilling, 1945 housing shortages and overt racism be damned.

Essaying the part of Randy Lane is the magnificent actor William Windom, who delivers here a performance of such depth and intensity that it’s almost painful to watch. In one of the most poignant moments of film ever captured and translated to television or movies, Windom delivers a passionate plea that breaks your heart:

“I rate something better than I got! Where does it say that every morning of a man’s life he’s got to Indian-wrestle with every young contender off the sidewalk, who’s got an itch to climb up a rung? Hey, Flaherty…Flaherty…I’ve put in my time. Understand? I’ve paid my dues. I shouldn’t have to get hustled to death in the daytime and die of loneliness every night. That’s not the dream! That’s not what it’s all about!”

Randy Lane is not without current day allies. Diane Baker plays a secretary who quietly loves this broken man. The more he pulls away from her, from the world, from life, the more passionately she loves and defends him. “Where you go, that’s where I go” she promises the just-fired Lane. Randy looks at her both longingly and sadly, telling her that where he is about to go she can’t follow.

But there is hope. Whether Serling believed in his own ending or not — Randy Lane, leaving behind the impending destruction of the bar and thus his own past, wanders into a nearby restaurant where his boss and the enamored Baker surprise him with their own rendition of “For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow” and a promise that he is wanted and needed — there is a promise that maybe, just maybe, this dance with the past and all of the cries in the night that goes with that melancholic and futile exercise may now be over and the embattled executive can get on about the business of living for the now and for the moment.

But…But. The ending as it aired seems forced and tacked on, perhaps a product of Jack Laird’s and/or Universal’s meddling. Before that moment of seemingly studio dictated happiness and resolution, Randy Lane heads back for one final visit to Tim Riley’s bar and he’s determined, despite the ghosts of his past that brush against him and whisper longingly in his tired ear attempting to push him away — after all, they are long dead, and he is not — to stake a claim to his past, to 1945 and a wife who is still alive in that golden year. Rebuffed, he cries out in anguish, perhaps speaking for Rod Serling himself:

“Wait a minute…Listen to me…I can’t stay here. I don’t have any place here. I’m an antique…a has-been. I don’t have any function here…I don’t have any purpose. You leave me now and I’m marooned! I can’t survive out there! Pop? Tim? They stacked the deck that way. They fix it so you get elbowed off the earth! You just don’t understand what’s going on now! The whole bloody world is coming apart at the seams. And I can’t hack it! I swear to God…I can’t hack it!”

It is a raw and powerful moment, made doubly poignant for the fact that this would be one of the last substantial pieces that Rod Serling wrote before his own death at the age of fifty in 1975. It’s almost as if Serling is already summarizing his own life as he lived it and, by 1971, was anticipating his own membership as one of the ghosts that reside in Tim Riley’s bar.

Follow Us

Follow Us