The only thing that’s changed more than movies since 1995 are computers, and the cultures surrounding them. Hackers, like all computer movies, was destined to have a short shelf-life as meaningful commentary, but it arrived with just the right amount of color and bluster, and just at the leading edge of the cyberspace wave through the culture, that it has maintained at least a little currency as a snapshot of cultural attitudes about what was then our newly digital world.

This film has been mostly forgotten except as a somewhat regrettable entry in Angelina Jolie’s deep back-catalog, but I believe that the past’s conception of its own near-future can sometimes illustrate perceptual gaps that occur in our current thinking about our present.

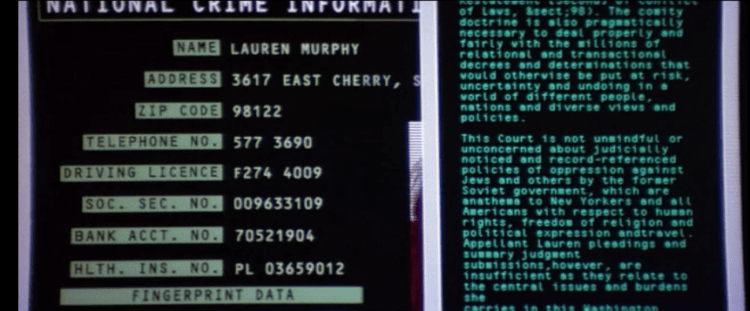

The above screen grab is from the second act of Hackers, where our villain “The Plague” is showing off how he has obtained access to the FBI profile of the mother of our hero, “Crash Override”. The shot lasts only a moment, enough to demonstrate through colorful graphics and disparate fonts and poor formatting the wide cross-section of data and software at The Plague’s fingertips. It is not meant to be perused, merely observed for its impact. But if you pause it just right, you can see enough of the filler text to see that what’s on the screen has nothing to do with the plot. By Googling certain distinctive phrases one can determine that the text on the right side comes from a 1994 New York City civil court case “Gotlib v. Ratsutsky”, which concerns the complicated divorce proceedings of two Russian nationals living in the U.S. The production designer was probably using the easiest to obtain legalistic public-record text he or she could quickly acquire. That is, easiest to obtain in 1995.

The simple fact that I was able to find which specific court case corresponded to a few hundred words of random text I copied off of a screen, from my sofa, using free software and ubiquitous hardware, means that we are living in the future that Crash Override and Acid Burn would have dreamt about. How their eyes would have glowed at the power of Google.

It is important for us to see our present as the realization of an entire past culture’s fantasy, and which was brought to life through their tireless efforts. To us who watched this digital “now” gradually envelop us like frogs in boiling water, we are painfully aware of the realities of the long slow grinding gradient of technological progress (and retrogress). But transport Lord Nikon to the New York City of today and it would not seem to him to be a work-in-progress; to him our world is the end-point, the fulfillment of one particular dream of the future.

One of the facets of Hackers that has caused it to age poorly is its insistence, like its predecessors such as Tron, to use surreal animations as visual metaphors for work being done in computers and across the Internet. The problem, of course, is that “real” computer hacking is, no matter how dramatic it might be, eminently uncinematic.

The problem that the movies of this era were trying to solve (which movies have largely given up on) is, if you can’t show how it looks to “hack”, how might you show how it feels?

There are moments in a programmer’s life, brief and very rare, when the system she is working with, this dumb wall of instructions and silicon, suddenly becomes transparent and holds no more secrets. The pattern of the software is revealed (or at least part of it) and the smallest details become easily predicted and derived through extrapolation. In these moments, a mental model of the system seems to hang in the air above her head, to be twisted and turned in whatever way she wants to get her answers.

It was never the intention of Hackers to teach you anything about computers (though you will learn if you pay attention; the screenwriting is fairly rigorous). Rather it was merely trying to give some little taste of this feeling. The task this film set out to accomplish was to use the language of cinema to communicate to the digital laity that working with computers at a deep level is a very different thing from working with adding machines or spreadsheets. There is an emotional component to the relationship which is ultimately part of the modern human experience and thus deserves to be part of our modern storytelling tradition.

But this responsibility was too much for a film of this budget to bear, and its attempt to facimile these internal experiences is not entirely successful. In the end, the film’s mid-90s earnestness causes it to collapse in on itself by the third act, and we are left with an artifact of a time when we were still convinced that movies that glorified very specific specialist careers like Backdraft and Daylight would be able to magically create their own dramatic attraction.

Having said all that, Hackers remains a valuable member of my Blu-Ray shelf not because of its cinematic value, but because of its place as a fun, risk-taking cultural snapshot of a very important time in the evolution of the personal computer, which, like all important historical eras, occurred when I was a teenager.

Follow Us

Follow Us