And then, Bosch all of a sudden got political. There have been shades of the larger political and legal systems at play in the world of Bosch, but never have they been front and center as they are in “High Low,” throwing Irving into a world of vague motivations and heavy exposition, creating an odd contrast between the upcoming election and Bosch’s various stories, with only a slight sense that the two are connected in any meaningful way. It’s an odd shift, moving from seven episodes where Bosch is featured in nearly every single scene, to “High Low,” which essentially splits Irving’s story with Bosch’s, even though the latter is really the only one we’ve spent time with this season.

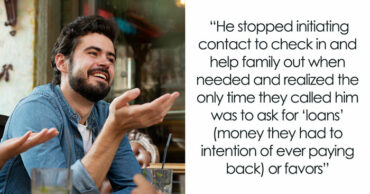

It makes those political stories lack the necessary context to have impact; while it’s fun to watch Irving bristle at having to work with the arrogant priest and all his political demands, there’s no dramatic weight to this at all. Bosch suddenly goes from revolving around its titular character to revolving around the socio-political culture of Los Angeles (and America, dropping a random, out of place Ferguson reference), and it doesn’t quite work, particularly since Irving’s been such a cipher as a character to this point. His material just doesn’t fit in with the rest of the season, a sudden shift in direction that seems to exist either to kill time, or set up future stories that will broaden the show’s scope in a potential second season – either way, it’s pretty ineffective, relying on a lot of talk about what people (unseen, unheard people, mostly) would say and do in potential political situations, a lot of foreshadowing and rhetoric that again, doesn’t mean a whole lot without a foundation to stand on.

The other half of “High Low,” the Bosch-focused material, can never really find its rhythm amongst all this, bouncing back from a mourning Raynard, to an angry Julia, to an increasingly arrogant and hypocritical Bosch, with no real anchor as it proceeds through its bread crumb chase of the week (centered around Albert’s skateboard, sold to Nicholas Trent by a foster family up the street). The show’s juggling act renders a lot of what happens weightless: Bosch and Raynard’s verbal jawing is becoming more frequent and leading, with Bosch talking about them “drawing closer”, and Raynard lamenting what happens in death to the only person he loved on the planet.

This leads to Raynard recreating the events of Marjorie Lowe’s (Bosch’s mother) murder in an alley dumpster, causing an emotional reaction from Bosch and reminding the audience that there’s something significant and cosmic about Raynard taunting Bosch – except that it’s just empty dramatics, a murder Bosch attributes to Raynard trying to “get to him.” The more ‘personal’ the crimes of this first season get, the less rewarding they’ve become, victims of the superficial mystique the show initially built up about Raynard’s connection to Bosch. They were both abused orphans who have problems with women and authority – in this episode, Bosch insults his wife and Brasher, both in hypocritical fashion; by the same token, Raynard wants empathy for murdering his mother – and most of all, they’re fixated with each other, one of those “personal” vendettas that is threatening to cheapen the dramatic arcs of the Delacroix murder and the chase to find Waits, however the two are connected.

Despite all this, I still find myself interested in where Bosch might be headed; with two episodes left, there’s no more time for Bosch to continue twiddling its thumbs, which means the fat should be trimmed in these final two hours, finally bringing to light the key connective tissue between story threads. Signs in “High Low” are not exactly promising, with the increasingly cyclical convolution of the Delacroix murder, and the prolonged manhunt for Waits that only half-heartedly attempts to build up empathy for a serial killer. If anything, “High Low” is a warning bell for Bosch to finally get to the point – let’s hope there’s something to be uncovered in these final two episodes.

[Photo via Amazon]

Follow Us

Follow Us