It’s only natural that with George A. Romero’s passing that people would look over his expansive legacy with eager eyes. I popped Night of the Living Dead in practically as soon as I heard the news and have put the series on a loop ever since.

And as I sat there with my girlfriend, curled up in the dark on the couch like I was ten years old again, I realized just how much was unique about the movie. I’m not just talking about how the movie is unique even within the horrific niche it carved out for itself back in the late sixties. The film, and its slipshod production, is one of the most genuinely fascinating studies in happenstance in the entire entertainment industry.

5) Night of the Living Dead was Romero’s directorial debut. Few directors have ever boasted as auspicious a beginning as George A. Romero. After graduating from film school in 1960, he started a modest career shooting commercials and TV segments. He even directed a sequence of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood where Rogers had a tonsillectomy.

Bored of commercials, Romero — along with a couple like-minded professionals — started work on what would eventually become Night of the Living Dead. Originally conceived as a quick-and-dirty $6,000 flick, with them and seven friends putting up $600 each, they eventually raised $114,000 to cover its costs. Although an impressive sum for some recent graduates with no real work in the industry, it was still a paltry sum even by the standards of the time.

And although the movie is among the all-time best of its kind, the greenness of its production crew is obvious for anybody to see. Romero fixates on abstract images and distractingly uses sharply angled shots seemingly just because he could. Barbara stands as one of the most abominably-written female characters of any classic movie, and the actress playing her doesn’t do her any favors either. It’s a slapdash production by an ambitious young crew that was more eager than experienced — and it shows — but it’s telling just how solid a foundation they had to work with that the film remains so revered despite these setbacks.

4) Ben, the film’s protagonist, was never meant to be Black. The plan for the original $6,000 was to afford 10 people. While that number naturally increased to reflect its eventual budget, they lacked the funds, infrastructure and connections that a major, or even minor, studio would have had access to. They had to work with what they could afford and only had word of mouth to drum up interested thespians.

Duane Jones, a fresh-faced Black actor who had never appeared in a movie before, got the film’s lead role simply because he was the best actor to audition for the film. Romero never envisioned a minority actor headlining the film, but he didn’t have much of a choice when it came time to start filming.

This casting decision proved to be one of the happiest accidents of all. While Romero may not have foreseen the effect it would have on the resulting film, he embraced the added political subtext wholeheartedly, adding to its depth and lasting appeal.

3) Romero won the soundtrack in a bet. Without much of a budget to work with, Romero had to get creative with filling out the cinematic necessities. Film is expensive. Equipment is expensive. Location rentals are expensive. And then, of course, there are the actors.

An avid chess player for his entire life, Romero won the soundtrack that wound up being used in the film in a bet over a game he played with its composer. As it turned out, the uneasy chords and dramatic stings were perfect for the film. And when the score didn’t stretch out to quite the length of the film, the uneasy, chirping sounds of the night provided an uneasy sense of dread to compliment it.

2) Due to a clerical error, Romero never made a dime off the movie. In one of the great commercial injustices in the industry, Romero never saw any money for making Night of the Living Dead. Nobody did. An absolutely maddening quirk of copyright law saw the film enter the public domain — where anybody could print, distribute and remake it for free — as soon as it was released to theaters.

The film’s original title was actually Night of the Flesh Eaters, which was changed in the eleventh hour before it began its theatrical distribution. But while all of the promotional materials changed the title, the distributor neglected to include any information about its copyright status on the newly-printed documents. And, in accordance with the law as-written, made it fair use for anybody and everybody to use without paying the people who actually made the movie a thing.

Obviously the movie’s insane level of success made Romero’s career, with or without royalties from the film itself. The fact that he was able to make another five in the same series — these ones duly protected by the law — is proof positive that he was heads and shoulders above the competition, who cheaply (and frequently) remade his first film for the simple fact that they could.

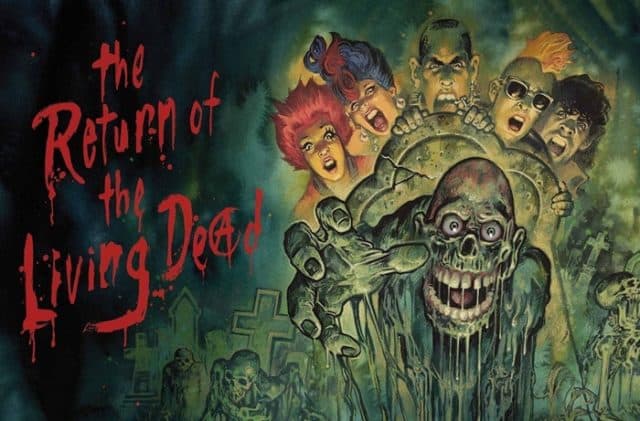

1) Romero and the film’s co-writer parted ways over what direction to take the series. Romero co-wrote Night of the Living Dead with like-minded filmmaker John Russo. But although they saw eye-to-eye on this one collaboration, the two men had drastically different ideas about where to take future installments of the franchise.

Prompted by the reception of the film’s Black star — and the inherent subtext of having him not only have to fight hoards of the starving undead, but the whole of White America along with it — Romero wanted to take future sequels in a bleaker, more socially-conscience direction. Russo, however, was more interested in the series as black comedy, playing up the absurdity of the premise and the protagonists’ bumbling attempts at working together against a multitudinous, but ultimately powerless, enemy.

It took some compromise and legal wrangling, but the two eventually worked out their differences. Romero could take the series — using the “Dead” monicker — in the direction he chose while Russo — using the “Living Dead” one — could do so as well. Russo wrote a novel, entitled Return of the Living Dead, which was an absurdist, tongue-and-cheek comedy about newly reanimated corpses taking over small town America, which was eventually adapted into an expansive film series of the same name.

Follow Us

Follow Us