A groundbreaking 3D modeling analysis has produced new evidence that the Shroud of Turin, long believed by some to be the burial cloth of Jesus Christ, could not have been draped over a human body at all.

Instead, the study concludes that the famous image was likely formed using a low-relief sculpture, adding ammunition to the theory that the shroud is a medieval artistic creation, not a biblical relic.

The discovery ignited fierce debate online, with one side calling it proof of a forgery and the other rejecting it.

“Christians don’t need proof of anything to believe that Jesus is the messiah. Faith is a gift; not everyone believes, and that’s alright,” a user wrote.

“Every sane person knew it couldn’t be real,” another replied.

3D artist uncovers new evidence that aims to prove the Shroud of Turin was never used to bury Jesus Christ

Image credits: Wikimedia Commons

The findings come from Cícero Moraes, a Brazilian digital designer and graphics expert known for his work in historical facial reconstructions.

Using a combination of historical evidence and facial forensics, the artist has not only been able to “revive” figures such as Ivan the Terrible, but also that of Egyptian Pharaoh Amenhotep III and the “Gilded Lady,” a remarkably well-preserved mummy who lived 1,500 years ago.

Image credits: Wikimedia Commons

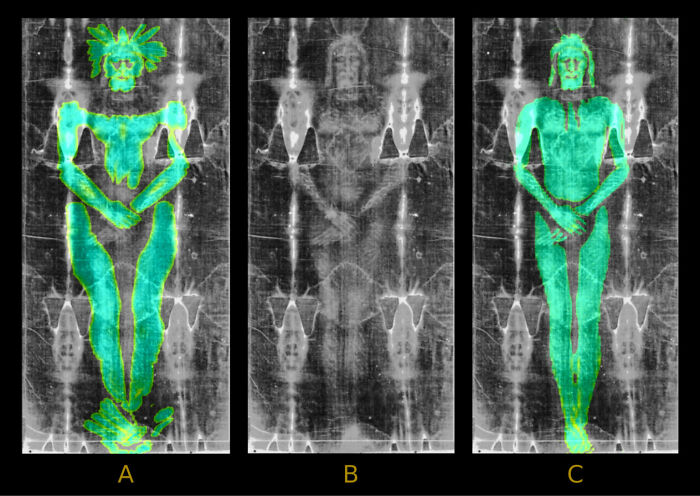

This time around, Moraes virtually draped digital fabric over two separate 3D models: one of a human body, and another of a low-relief sculpture: a type of carving in which the design is only slightly raised from the background.

The results were striking.

Image credits: Moraes, Archaeometry, 2025

“The image on the Shroud of Turin is more consistent with a low-relief matrix,” Moraes concluded.

“Such a matrix could have been made of wood, stone or metal and pigmented (or even heated) only in the areas of contact, producing the observed pattern.”

Moraes claims the shroud to be a medieval artistic creation made centuries after the passing of Jesus Christ

Image credits: Moraes, Archaeometry, 2025

The designer then compared the results of his simulations with high-resolution photos of the shroud taken in 1931.

Moraes found that the draping over the sculpture closely matched the actual cloth’s contours, while the simulation using a human body introduced distortions inconsistent with the famous image.

Image credits: Moraes, Archaeometry, 2025

The discovery reignited a centuries-long debate surrounding the Shroud of Turin.

The cloth first appeared in historical records in 1354 and has captivated scholars, believers, and skeptics alike ever since. It bears the faint image of a man with apparent crucifixion wounds, something that believers consider key to its authenticity.

“I suppose the statue was bleeding as well, that’s how all the blood stains got on it, especially the one right in the area where Jesus was speared in his lower right ribs by the Roman soldier,” a user wrote, sarcastically.

Image credits: Moraes, Archaeometry, 2025

The shroud’s legitimacy has long been questioned, with Moraes’ analysis joining a growing body of research that seeks to strip the relic of its allegedly sacred qualities.

The shroud’s legitimacy took a major blow in 1989, when radiocarbon dating conducted by three separate laboratories found that the cloth most likely dates between 1260 and 1390. That timeline is centuries too late to have been present at the crucifixion.

The process measures the age of organic materials by measuring the decay of carbon-14, a chemical element that slowly diminishes over time in non-living tissue.

Christianity experts were quick to dismiss Moraes’ claims, arguing that he didn’t discover anything new

Image credits: Wikimedia Commons

Still, not everyone is convinced. Some researchers have argued that contamination from centuries of handling and storage could have skewed the carbon dating. A 2022 study even proposed that the shroud could plausibly be 2,000 years old.

Andrea Nicolotti, a professor of the history of Christianity at the University of Turin, was quick to dismiss Moraes’ findings as irrelevant.

“Moraes has certainly created some beautiful images with the help of software,” Nicolotti wrote in Skeptic Magazine. “But he certainly did not uncover anything that we did not already know.”

Image credits: Wikimedia Commons

Her reaction mimics the back-and-forth between believers, Christianity experts, scientists, and skeptics that the shroud has motivated for decades.

Research from the 1970s suggested the bloodstains on the cloth were consistent with crucifixion, but a 2018 analysis challenged that, finding the patterns didn’t align with how blood would realistically flow on a crucified body, and arguing that they were placed for effect.

Whether authentic or not one thing is certain, the Shroud of Turin remains an object of profound fascination centuries after its discovery.

“Overwhelming.” With each side confident in their beliefs, it seems Moraes’ findings did little to sway the faithful

Follow Us

Follow Us