Bringing long-lost animals back to life is no longer just a fantasy. Scientists are inching closer to turning the dream of revival into one of the most bizarre realities of the 21st century.

Massive funding and growing buzz surround cutting-edge de-extinction labs, the CRISPR gene-editing tool, and selective back-breeding methods.

According to Ben Lamm, CEO and co-founder of Colossal Biosciences, these approaches are now “so powerful” in today’s scientific landscape (per Business Insider).

The once-impossible “de-extinction” mission is grabbing headlines worldwide with bold promises to revive the woolly mammoth, the massive Steller’s sea cow, the flightless dodo, and the peculiar heath hen.

While skeptics question whether de-extinction is even possible, scientists are actively pursuing this ethically complex and ecologically bold endeavor. In fact, a few long-lost species have already been brought back to life.

Woolly Mammoth

“Bring back the woolly mammoth!” urges Silicon Valley investor Tim Draper, founder of DFJ and Draper Associates (per Colossal).

Texas-based Colossal Biosciences aims to do just that. With over $400 million in funding, the company spearheads a high-profile mission to combine conservation with the resurrection of the extinct Mammuthus primigenius.

Surprisingly, reviving a mammoth in today’s age isn’t far-fetched, at least in theory.

Instead of using frog DNA like in Jurassic Park, Colossal plans to work with the Asian elephant, the mammoth’s closest living relative.

Using cutting-edge AI tools, scientists at Colossal analyze ancient mammoth DNA from Siberia and Alaska, dating back 3,500 to 700,000 years. This helps them pinpoint the genetic traits that define the species.

“It’s like reverse Jurassic Park,” said Colossal CEO Ben Lamm. Rather than patching gaps in old DNA with unrelated species, the goal is to add mammoth genes to a living relative.

The result: a “mammophant,” a hybrid creature designed to resemble and behave like a woolly mammoth (via NPR).

Draper applauded the company’s trailblazing approach: “Colossal will be the first to use CRISPR to de-extinct species, starting with the mammoth. Their software and breakthroughs could revolutionize genomics, disease treatment, and biotech.”

Still, not everyone is optimistic. Research led by Professor Mary Edwards at the University of Southampton found that Ice Age mammal extinctions were driven mainly by climate-related vegetation changes (per Phys.org).

In other words, reviving mammoths may not significantly impact climate change as some supporters hope.

Dodo

The hashtag #BringBackTheDodo started trending after scientists announced a major breakthrough in lab-grown germ cells in January 2025 (per The Washington Post).

Beth Shapiro, Colossal’s chief science officer and expert in extinct animal genetics, now claims that reviving the dodo is scientifically possible.

The bird, native to Mauritius, vanished more than 300 years ago (via Mauritius Attractions).

“As the world changes and technology changes, as a scientist, you should adapt,” Shapiro said, casually slipping on a white lab coat over her arm tattoo of a dodo.

“And your opinion of what is possible should adapt to that.”

Shapiro’s team has determined that the dodo is essentially an oversized pigeon.

This key finding led them to extract primordial germ cells from an ordinary pigeon egg. After extensive genetic modification, those cells could yield a near replica of the extinct dodo.

The science appears solid. The dodo, a one-meter-tall bird with stubby wings, was a distant relative of the Asian pigeon.

Too heavy and slow to fly, it was ultimately doomed by the human-driven destruction of its habitat in Mauritius.

Tasmanian Tiger (Thylacine)

Scientists have made a major breakthrough in efforts to bring back the Tasmanian tiger, also known as the thylacine.

Professor Andrew Pask, who leads the Thylacine Integrated Genetic Restoration Research (TIGRR) lab at the University of Melbourne, described the progress as a “major leap forward” (per ABC News).

Excitement is building around the revival plan, thanks partly to a $10 million grant from Colossal Biosciences to Pask’s team (per The Sydney Morning Herald).

“We will bring something back, 100 percent,” Pask affirmed. “There is nothing in the science that is insurmountable.”

The last known thylacine died in captivity in 1936 at Hobart Zoo, having frozen overnight after being locked out of its shelter (via The Sydney Morning Herald).

A pivotal moment in the project came with the discovery of a well-preserved thylacine head containing intact RNA molecules (per The Guardian).

“It was literally a head in a bucket of ethanol in the back of a cupboard that had just been dumped there with all the skin removed, and been sitting there for about 110 years,” Pask recalled.

“This was the miracle that happened with this specimen. It blew my mind.”

Passenger Pigeon

“The last known passenger pigeon, a bird named Martha, died at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914. Its death helped spark conservation laws aimed at protecting endangered species in the US,” the Wall Street Journal reported.

Today, scientists are nearing the possibility of reviving this extinct species by sequencing the genome of its closest living relative, the band-tailed pigeon.

“These are the first pigeons in history with reproductive systems that carry the Cas9 gene, a core component of the CRISPR gene-editing tool. Their squabs will inherit this gene in every cell, enabling scientists to insert DNA from the extinct passenger pigeon,” the journal explained.

If successful, passenger pigeons would become the first living animals modified to include traits from an extinct species.

But there’s a catch: these birds may vanish again even if revived.

“The habitat the passenger pigeons need to survive is also extinct,” warned Beth Shapiro, a professor at UC Santa Cruz and author of How to Clone a Mammoth (per Wall Street Journal).

Pyrenean Ibex (Bucardo)

In an astonishing scientific feat, Spanish and French researchers brought the extinct Pyrenean ibex, or bucardo, back to life, only to witness it go extinct again (via National Geographic).

After numerous failed attempts, scientists injected nuclei from preserved bucardo cells into goat eggs that had been stripped of their DNA. Out of 57 implantations, just one surrogate successfully carried the embryo to term.

The cloned ibex, a 4.5-pound female, was delivered via cesarean section. Tragically, she died just ten minutes after birth, gasping for breath with her tongue hanging out, a heartbreaking moment for the research team.

The scientists concluded, “At present, it can be assumed that cloning is not a very effective way to preserve endangered species. […] However, in species as bucardo, cloning is the only possibility to avoid its complete disappearance” (per Forbes).

Their findings emphasize the importance of storing tissue and cell samples from endangered species to improve the success of future cloning efforts.

Gastric-Brooding Frog

UNSW Professor Mike Archer and his team successfully developed early-stage cloned embryos with the DNA of the extinct gastric-brooding frog (per UNSW).

The Rheobatrachus silus, an Australian amphibian, went extinct in 1983. Thanks to somatic cell nuclear transfer, there’s renewed optimism about bringing the ground-dwelling frog back.

“We are not giving up. We are still hopeful that we will succeed and be able to bring this wonderful frog back to life within a few years,” said Archer.

“In fact, we have an ethical responsibility to keep going and to try to undo the harm that we have done in contributing to its extinction.”

This frog species was unique for its reproductive method: it swallowed fertilized eggs and brooded the offspring in its stomach, eventually giving birth through its mouth.

Even if the frog isn’t revived, its bizarre biology presents exciting potential for biomedical research.

Great Auk

Genetic research and DNA sequencing advances have sparked new optimism about reviving the Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis). This flightless, penguin-like bird vanished in the 19th century (per The Times of India).

If successful, the Great Auk would return to the planet for the first time since it was hunted to extinction in the mid-1800s (per Arctic Portal).

Human demand for meat, feathers, and eggs, combined with habitat loss, led to the species’ collapse.

Explorer George Cartwright foresaw this fate in 1785: “A boat came in from Funk Island laden with birds, chiefly penguins [Great Auks]. But it has been customary of late years, for several crews of men to live all summer on that island, for the sole purpose of killing birds for the sake of their feathers. The destruction which they have made is incredible. If a stop is not soon put to that practice, the whole breed will be diminished to almost nothing” (per Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History).

Reviving the Great Auk could be vital in restoring coastal ecosystems and strengthening marine food webs.

As seabirds face mounting threats, global conservationists are intensifying efforts to preserve critical feeding grounds (via Hakai Magazine).

Steller’s Sea Cow

Steller’s sea cow, a massive marine mammal from the Sirenia order, once seemed more mythical than real (per Arctic Sirenia).

First documented by 18th-century explorer Georg Steller during Vitus Bering’s expedition, the species was declared extinct by 1768.

Efforts to bring the animal back are gaining traction, largely due to a novel approach involving an “artificial womb” to initiate embryonic development at the cellular level.

If revived, the 5-ton giant could play a critical role in maintaining kelp forest ecosystems, which help absorb carbon and protect coastal areas from storms (per European Wilderness Society).

Scientists believe the dugong, the sea cow’s closest living relative, may be key to its comeback.

However, the significant size difference between the two species presents a major challenge to the plan.

Quagga

A determined South African project launched in 1987 aims to bring back the quagga, a unique subspecies of the plains zebra.

A significant milestone came with the birth of the rare “Rau” quagga in Somerset West, a foal with the species’ signature stripes only on its head, neck, and front torso (per The Witness).

Researchers behind the decades-long initiative have shown that back-breeding is a viable strategy, since the quagga is genetically classified as a subspecies of the plains zebra (via Medical University of Lublin).

The Quagga Project is a prime example of how selective breeding can mimic extinct species.

However, outcomes may vary depending on environmental conditions, according to Colossal.

In contrast, genome editing reshapes DNA directly by deleting, inserting, or replacing sequences.

Heath Hen

“The Heath Hen could come back” is a bold claim from Revive & Restore, grounded in a three-step plan: genome research, revival, and restoration.

The species went extinct in 1932, dwindling down to a single population on Martha’s Vineyard, where officials had established a preserve in a last-ditch effort to save it.

Thanks to major advances in genetic science, Heath Hen DNA can now be restored.

Its closest living relative, the North American prairie chicken, provides a useful genetic match. This makes gene comparison, transfer, and surrogate parenting more feasible (per Revive & Restore).

It’s been decades since the last Heath Hen, nicknamed Booming Ben, vanished.

Many in New England are cheering on the de-extinction effort in hopes of reviving their lost wild bird.

Aurochs

Once called “the most important animal in the history of mankind,” the Aurochs helped shape European ecosystems until its extinction in 1627, largely due to overhunting (per Rewilding Europe).

Now, centuries later, efforts led by Rewilding Portugal and the Taurus Foundation are working to revive the Aurochs through selective breeding programs (per CNN).

“We wanted to develop a substitute for what Aurochs used to be,” said Ronald Goderie, director of the Taurus Foundation, who launched the program in 2008.

Remarkably, domestic cattle still retain many of the original Aurochs’ genes.

Biologist Prata, who grew up near Portugal’s Côa River, emphasized that it’s not just about rewilding for nature’s sake.

“Some ecosystem elements are missing — habitats, processes, or species that matter,” he explained.

That’s where large herbivores come in. “Large grazers are engineers. They influence plant distribution, recycle nutrients, and create opportunities for other species,” Prata said.

Northern White Rhino

BioRescue scientists are racing against time to save the planet’s rarest rhino species (per Phys.org). Following the death of Sudan, the last male Northern white rhino, in 2018 at age 45, hopes now rest on science (per Scientific American).

Only two Northern white rhinos remain, Najin and her daughter Fatu. “We will save them,” vowed Jan Stejskal, BioRescue’s project coordinator.

Neither rhino can carry a pregnancy, but Fatu can still produce viable eggs, making her a candidate for in vitro fertilization.

“We hope to achieve the first successful pregnancy with the northern rhino embryo this year,” said Stejskal.

In a promising step, BioRescue transferred a rhino embryo into a surrogate (per Leibniz-IZW).

In 2023, a Southern white rhino embryo created via IVF was implanted into a Southern white rhino at Kenya’s Ol Pejeta Conservancy. The team later confirmed a healthy 70-day pregnancy with a 6.4 cm male embryo.

This breakthrough raised cautious optimism that the Northern white rhino might be pulled back from the edge of extinction.

Moa

The extinct moa of New Zealand may make a surprising comeback in the 21st century, thanks to a breakthrough genome sequencing effort.

In May 2024, scientists announced they had reconstructed 85% of the bird’s genome (per Science).

Researchers sequenced the DNA of the flightless little bush moa using ancient material extracted from a fossil bone found in New Zealand’s South Island.

Moa birds disappeared around 600 years ago due to a combination of overhunting and habitat loss (per National Museum of Ireland).

These giant birds hold deep cultural significance in Māori mythology, where they symbolize power and endurance.

Since their extinction, they’ve become a haunting symbol of the fragility of biodiversity and indigenous heritage.

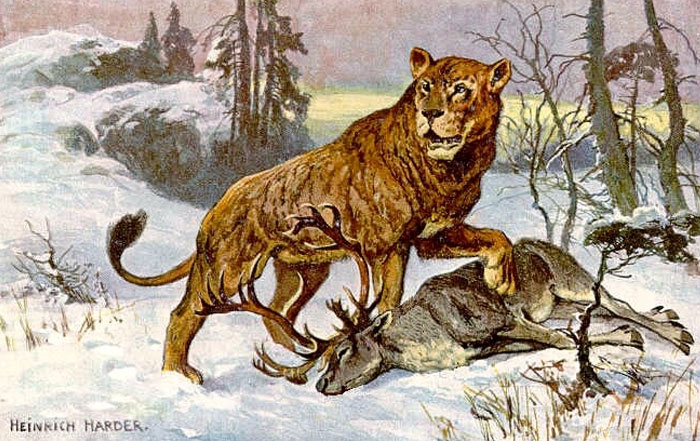

Cave Lion

A frozen cave lion cub was discovered in the Siberian Arctic in remarkably preserved condition.

Its fur, whiskers, teeth, organs, and soft tissues remained intact after 28,000 years (per CNN).

Nicknamed Sparta, the cub sparked renewed interest in reviving the Ice Age predator.

“Sparta is probably the best preserved Ice Age animal ever found,” said Love Dalen, a professor of evolutionary genetics at the Centre for Palaeogenetics in Stockholm.

“She even had the whiskers preserved.”

Revival efforts are connected to Pleistocene Park, a project aimed at restoring grazing ecosystems in the Arctic, modeled after the ancient mammoth steppe (per Pleistocene Park).

This once-vast biome, dominant 25,000 years ago, vanished due to climate change (per Eos).

Today, Pleistocene Park houses a range of herbivores, including bison, moose, musk oxen, and camels, hoping to rebuild a thriving ecosystem.

Follow Us

Follow Us