Human history is much deeper, more complex, and more nuanced than you probably remember from school. Many history books, especially the ones you read in class, focus on major events like battles and treaties. Unfortunately, one consequence of this is that women often get sidelined, as the spotlight rests mainly on men.

However, the ‘Women In World History’ social media project aims to change all of this by shining the spotlight on women over the ages. We’ve collected some of the most powerful stories about women from history, as featured there, to give you a deeper appreciation for the past. You’ll find them below.

More info: Instagram | Threads | Facebook

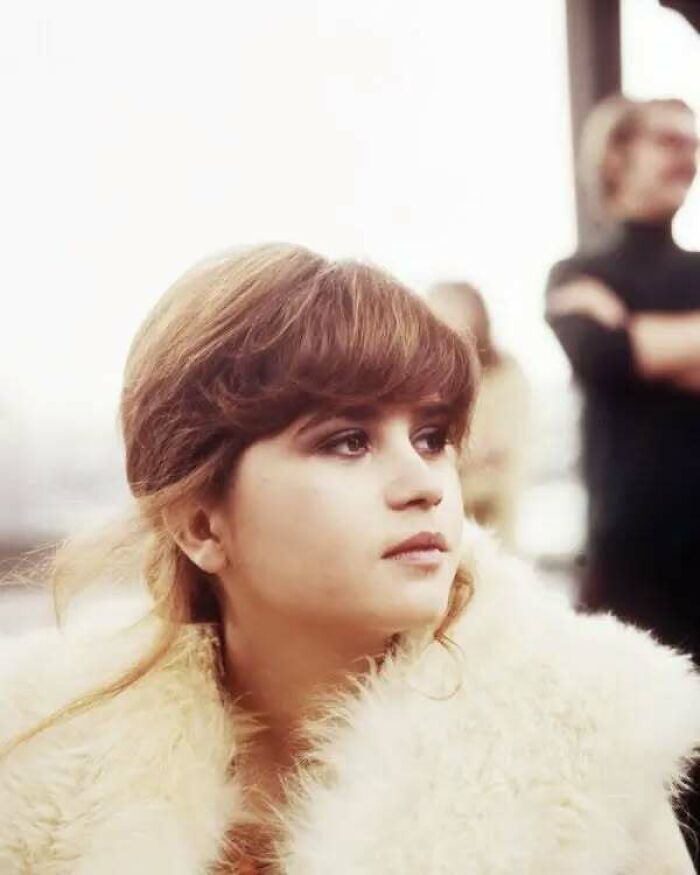

#1

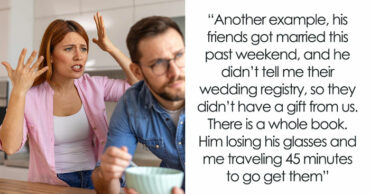

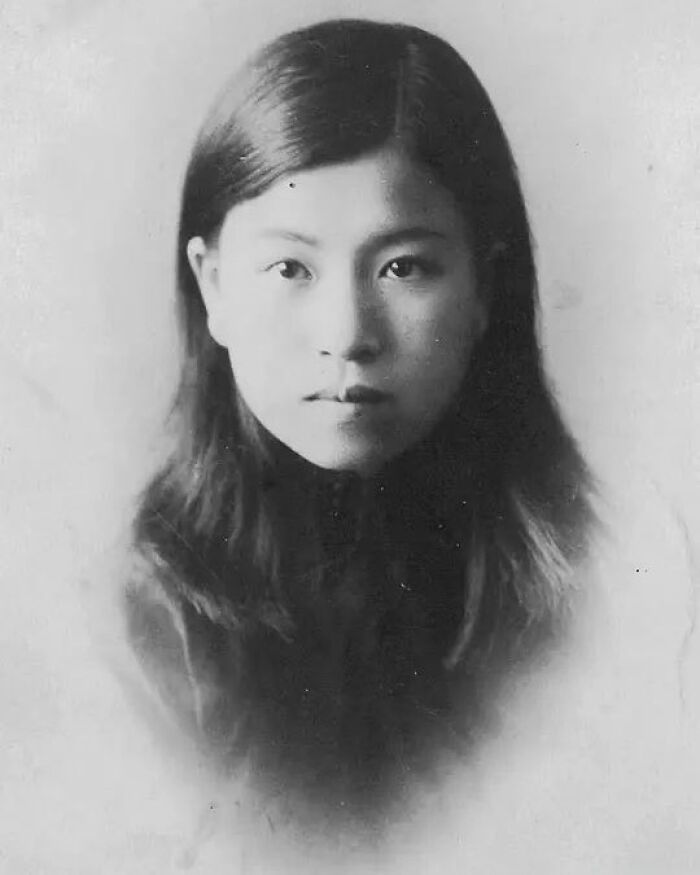

In 1905, a rare photograph captured a geisha just after washing her hair, before it was styled into the elaborate coiffures that defined her appearance.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#2

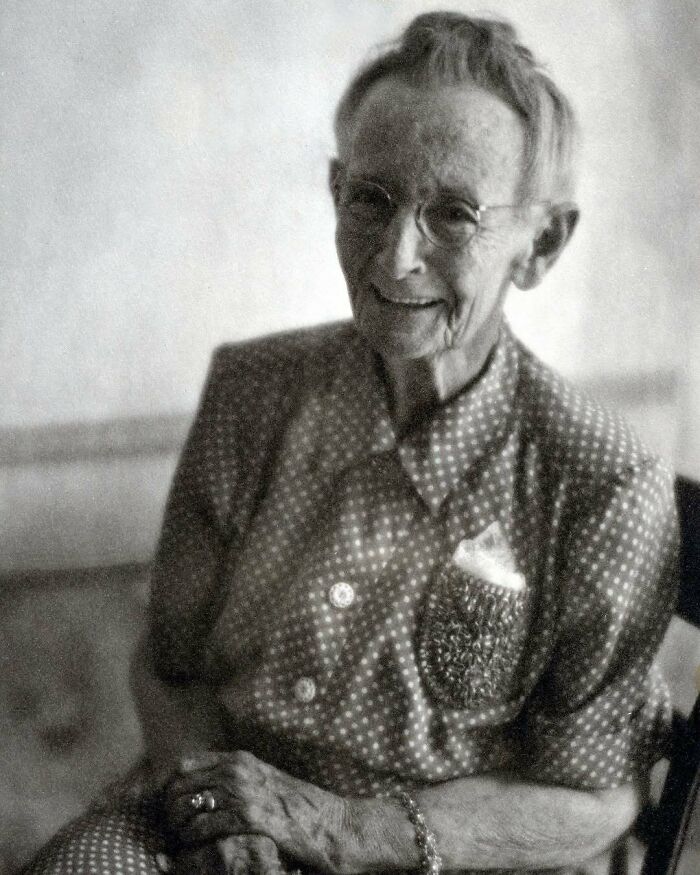

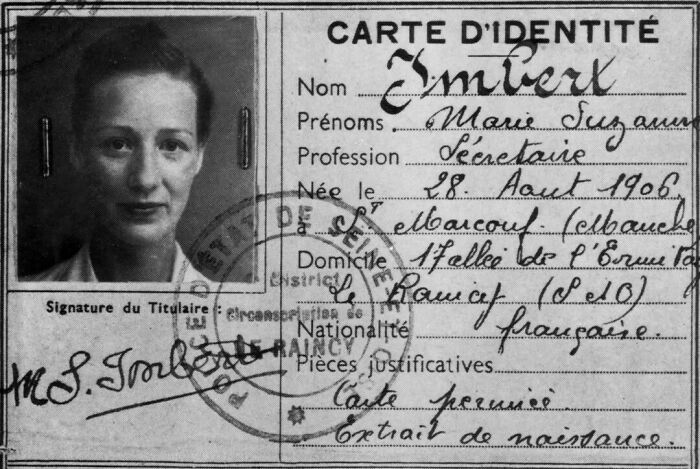

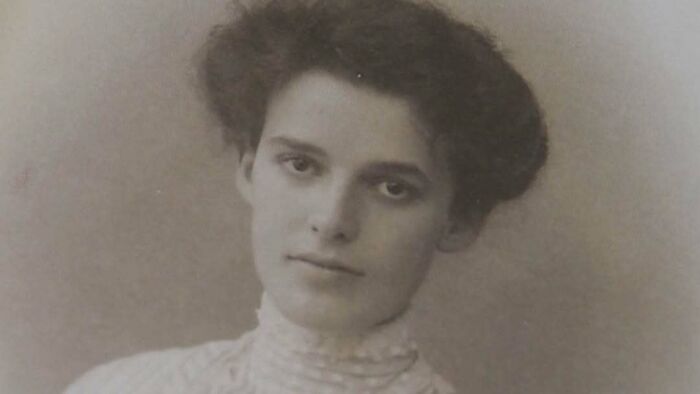

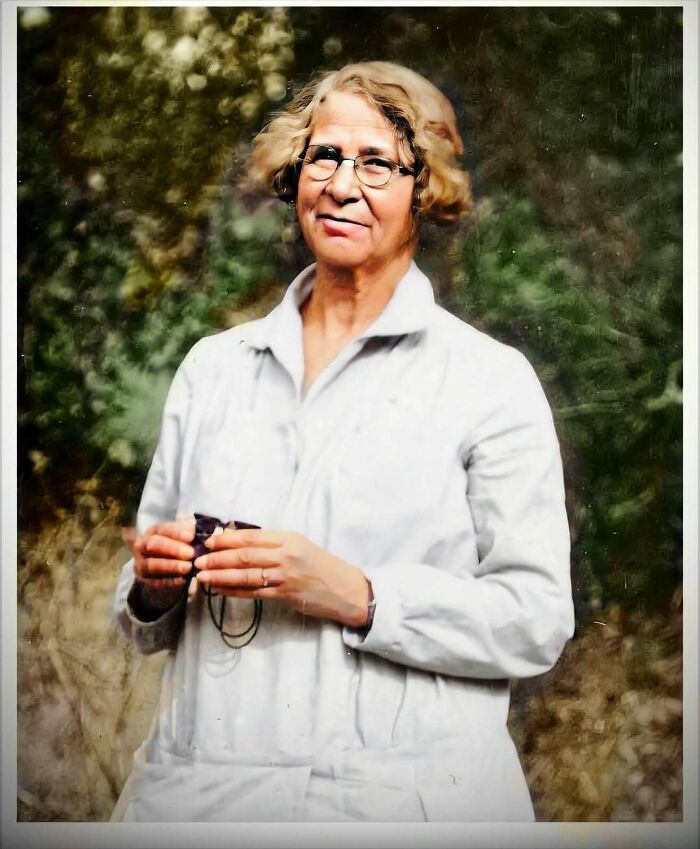

Josette Molland’s life was one of extraordinary courage, forged in the darkest of times. At just twenty years old, she was an art student in Lyon when she made the choice to resist the Nazi occupation. While many at her age were thinking of careers or romance, she risked everything by joining the Resistance. Her skill with drawing and detail became a weapon of survival; she forged rubber stamps used to create false identity papers that saved countless Jewish refugees and Allied soldiers. Every stroke of ink was an act of defiance, a quiet rebellion against tyranny, and a lifeline for those desperate to escape.

Her bravery did not go unnoticed. The Gestapo, led by the ruthless Klaus Barbie—the “Butcher of Lyon”—set out to destroy the underground network she was part of. Josette was captured, brutally tortured, and deported to the Ravensbrück concentration camp. Later, she was sent to a forced labor camp where survival meant enduring unimaginable cruelty, starvation, and exhaustion. Years later, she admitted that words could never truly describe the suffering: each day she believed might be her last. And yet, she endured.

When the war ended and liberation came, Josette could have chosen silence, as so many survivors did to protect themselves from reliving the trauma. Instead, she turned her pain into a tool for education and remembrance. She painted fifteen haunting images in a raw, almost folk-art style, each one telling a story of the camps. She paired them with unflinching descriptions that revealed the inhumanity she had witnessed: prisoners executed for exhaustion, gold teeth wrenched from mouths to feed the Nazi war machine. Through her art, she demanded that the young never forget what fascism looked like up close, so it could never take root again.

Her death at one hundred years old was marked with the same spirit of resistance that defined her youth. At her funeral, “La Marseillaise” and the “Chant des Partisans” were sung—songs that once carried courage through occupied France. She was buried with full military honors, a reminder that even in her frailty and old age, she was still a soldier, still a fighter.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#3

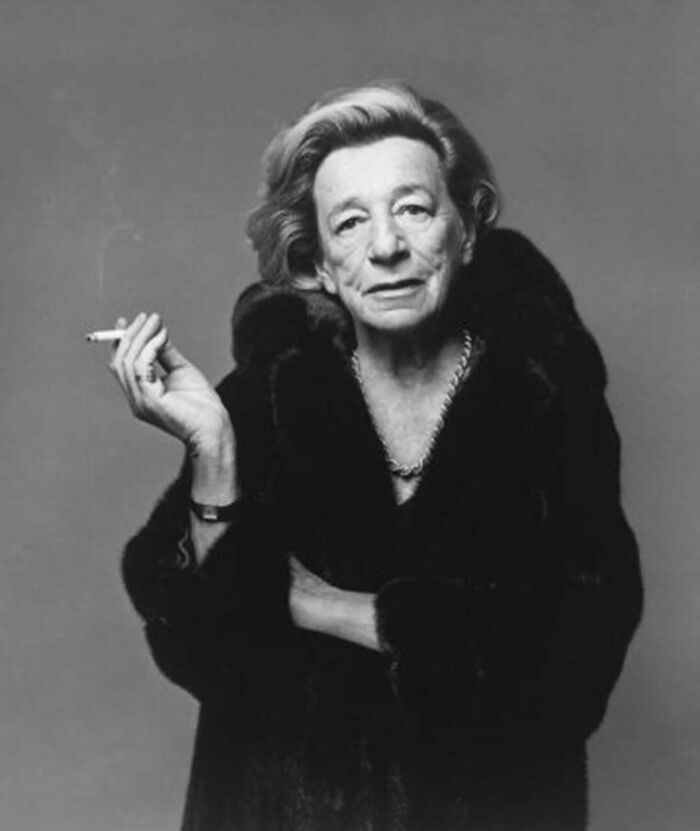

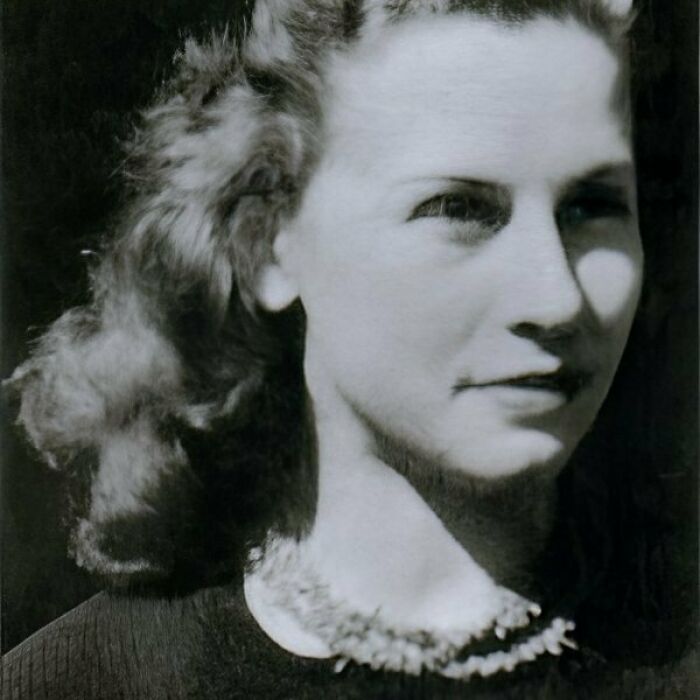

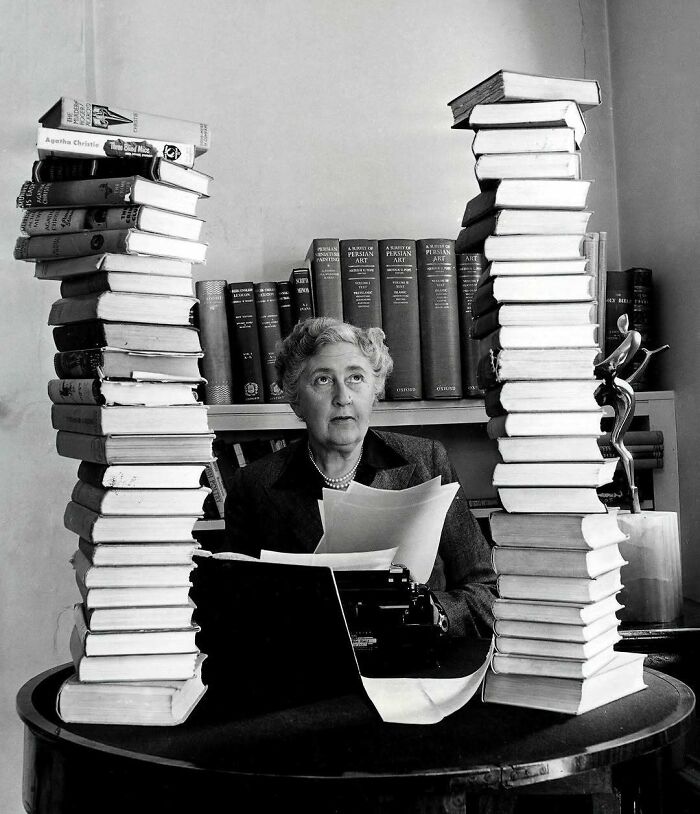

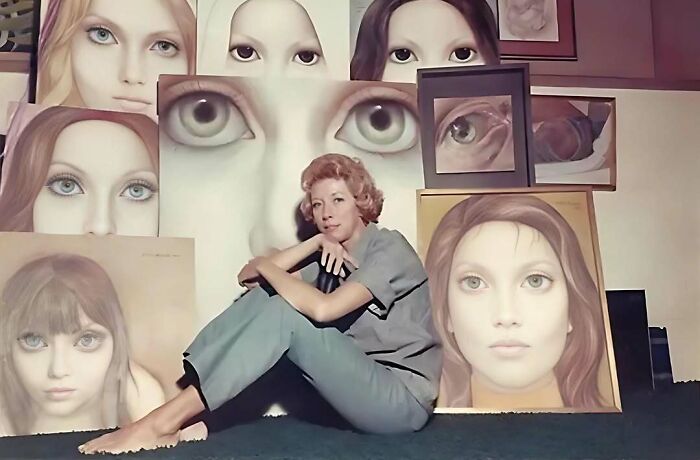

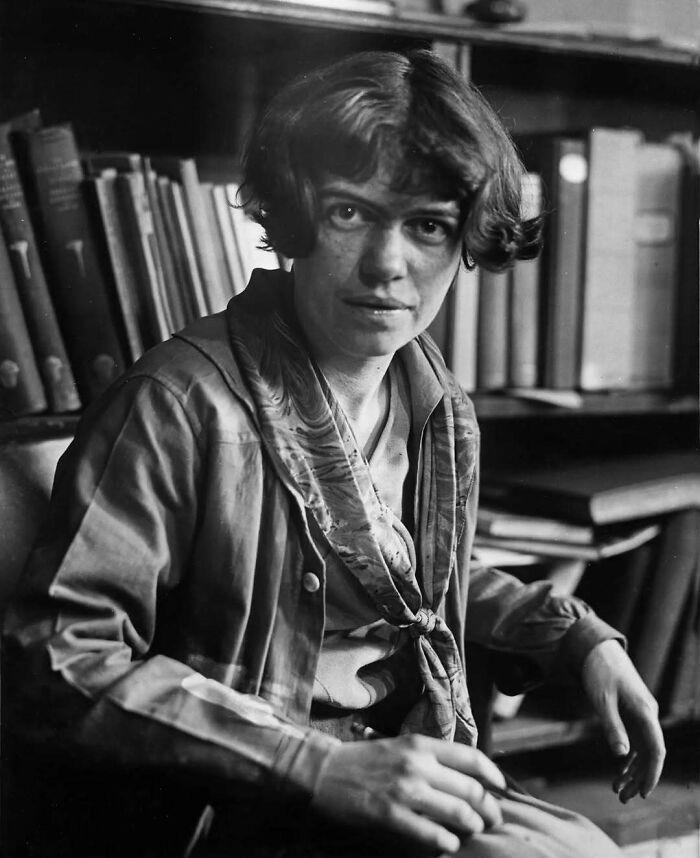

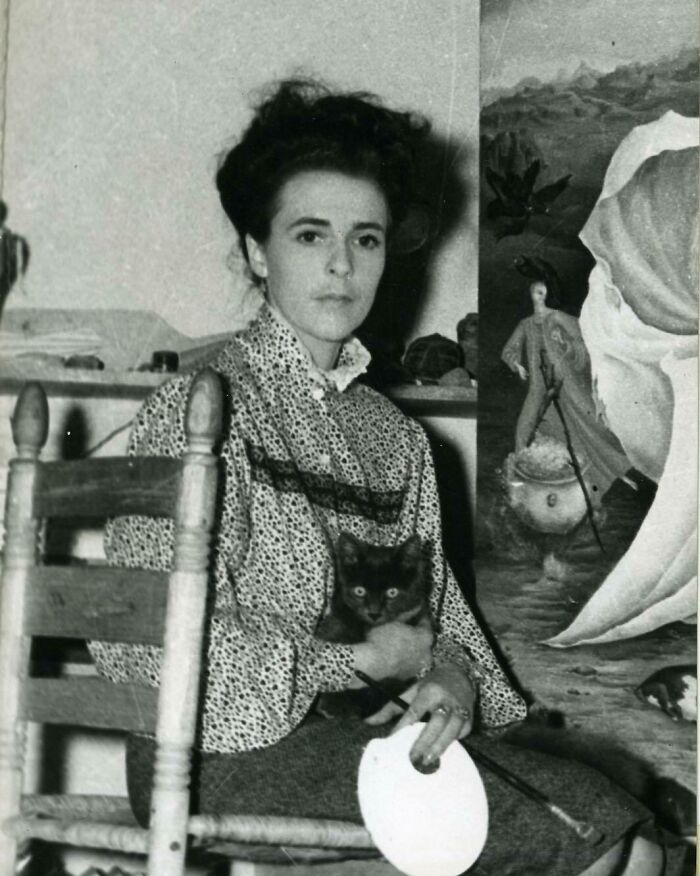

A woman steps out of a cab, juggling bags of groceries, ready to get on with another ordinary day. Before she can put the key in the door, a reporter appears, breathless, telling her she’s just won the Nobel Prize in Literature. Doris Lessing, 87 years old, doesn’t gasp, doesn’t clutch her chest, doesn’t cry. She gives a wry smile, sits down on her doorstep, and says, “Oh, Christ.”

It was classic Lessing—direct, unsentimental, and deeply human. For decades, she had poured her clear-eyed observations of society, politics, and gender into more than 50 books, cutting through the polite pretensions of post-war Britain, colonial Africa, and the feminist movements that tried to claim her. She was never interested in being celebrated. She was interested in truth, and she wrote with a sharpness that could both comfort and unsettle, exploring the intimate and the political with the same fierce honesty.

Born in Iran and raised in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), she saw firsthand the realities of racism and the suffocation of colonial life. Those experiences bled into her work, particularly The Grass Is Singing and her iconic The Golden Notebook, which dissected women’s lives and mental fragmentation with a rawness that resonated with women across generations. She lived boldly, joining the Communist Party when it aligned with her convictions and leaving it just as boldly when it disappointed her ideals, never afraid to revise her beliefs as she revised her sentences.

By the time the Nobel Committee recognized her, Lessing was past the age when the world typically expects women to be relevant, let alone honored on a global stage. But there she was, seated on her front step, groceries at her feet, fielding questions about a lifetime of words that had pierced through the noise of the 20th century. She became the oldest person ever to win the Nobel in Literature, a reminder that a woman’s voice does not expire, that the stories she tells—about war, about motherhood, about aging, about injustice—can continue to shake the world. She died at the age of 94 in 2013.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

Gender discrimination and systemic bias, while being pushed back against, are still prevalent in society. Not just in history, but even in the world of science, where objectivity should be the highest standard.

According to Nature magazine, women are “less likely to be named as authors on articles or as inventors on patents than are their male team mates, despite doing the same amount of work.”

This is, in part, due to the fact that women’s contributions to research are often not known, not appreciated, or ignored.

“There is a well-documented gender-based productivity gap in science. On average, women publish fewer papers than men, secure fewer grants and fill fewer leadership positions. Previous research has suggested that women are less productive because scientific working environments are less welcoming to them, they hold different positions from men or they have greater family responsibilities. But a 2020 study also hinted that women’s research is undervalued,” Nature magazine explains.

Not only did the research find that women were less likely than men to be named as a study author or inventor, but they were also less likely to be cited by other researchers, even when published in the same journals.

#4

In medieval Europe, there were women who quietly stepped outside the roles expected of them, choosing lives that didn’t quite fit into the Church’s rigid boxes. They were called Beguines. Unlike nuns, they didn’t take lifelong vows, and unlike wives, they didn’t bind themselves to marriage. Instead, they built their own communities—places where women lived together, prayed together, and supported themselves through weaving, nursing, or teaching.

These women carved out rare independence in a world that gave them few choices. A #Beguine could own property, keep her earnings, and even decide to leave the community if she wished. Some lived simply, devoted to charity, while others became mystics and writers, producing some of the most profound spiritual works of their time. At a moment in history when women’s voices were so often silenced, theirs rose boldly, full of longing and power.

They weren’t always trusted. The Church sometimes saw their freedom as dangerous, their visions as too radical, their independence as a threat. Many faced suspicion or even persecution. And yet, the Beguines endured for centuries, creating a model of female solidarity and spiritual life that was neither cloistered nor controlled.

Their legacy lingers quietly, reminding us that women have always found ways to step outside the boundaries set for them, to create their own spaces, and to live by their own terms—even in times when it seemed impossible.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#5

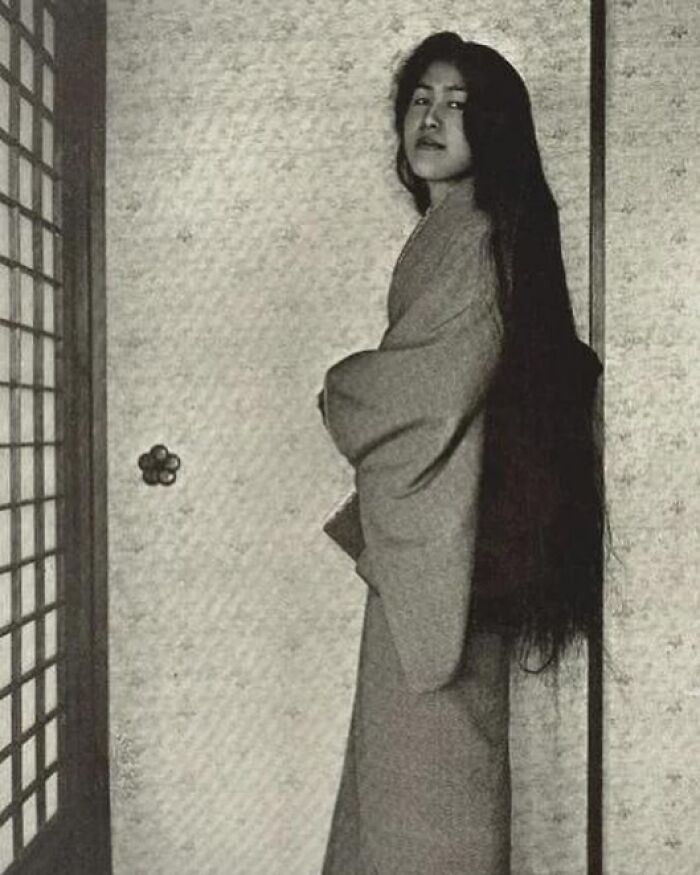

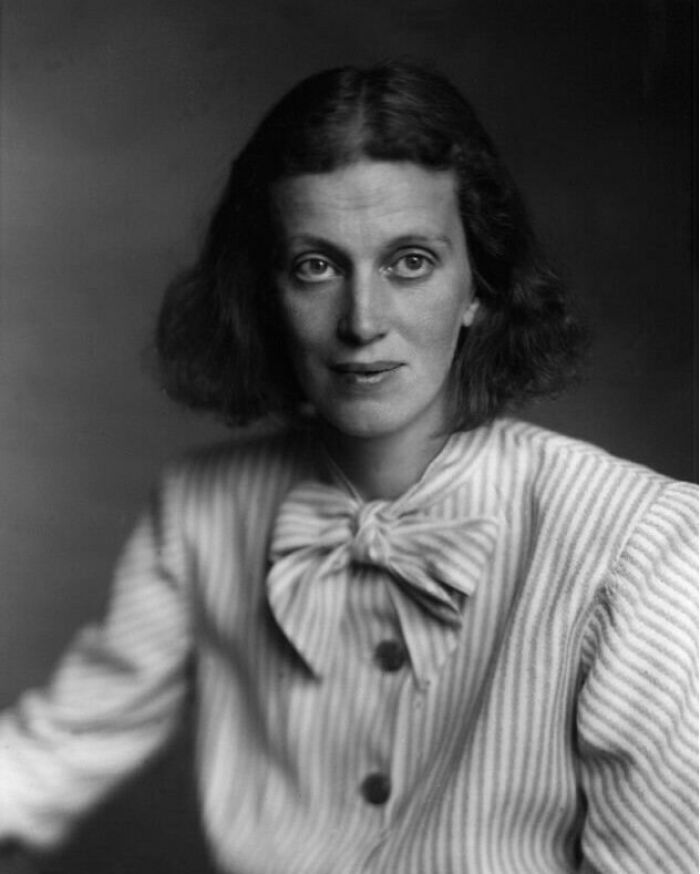

When Frida Kahlo and Georgia O’Keeffe first crossed paths in New York in the early 1930s, the connection between them was immediate. Kahlo was still on the cusp of being recognized as an artist in her own right, while O’Keeffe had already established herself as a force in modern American painting. Despite the differences in their careers, they saw in each other something familiar: bold women navigating art, love, and illness with uncompromising honesty.

Their time together was marked by warmth, humor, and a touch of mischief. Stories survive of them going out drinking with friends, laughing and singing together into the night. Kahlo’s affection for O’Keeffe was more than casual; she admired her strength, her work, and the way she carved out independence in a world that demanded conformity from women. In letters, Kahlo’s tone carried both tenderness and longing, suggesting that her feelings may have run deeper than friendship, though how far it went is left to interpretation.

Both women endured fragile health at different points, and here their bond became even clearer. When O’Keeffe suffered a breakdown and spent time recovering, Kahlo reached out with concern and gestures of kindness. Years later, when Kahlo was bedridden and in pain, O’Keeffe made the journey to Mexico to visit her. These acts of care reflected the rare kind of intimacy they shared—one grounded not only in admiration, but in the recognition of struggle.

Kahlo also left traces of O’Keeffe in her art. Certain flowers that O’Keeffe had painted obsessively appeared in Kahlo’s canvases, but reimagined through her own lens, layered with personal and cultural meaning. It was as though Kahlo was entering into a conversation with O’Keeffe on the canvas, acknowledging her influence while transforming it into something distinctly her own.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#6

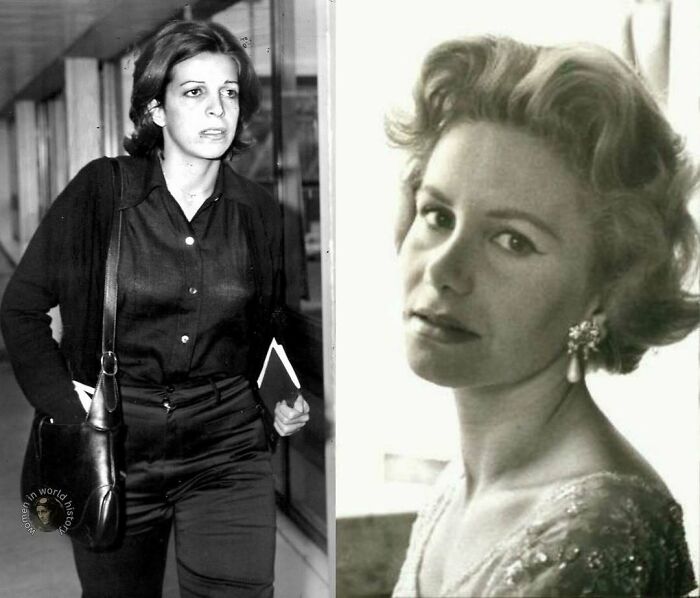

Ashley Judd’s story is one of those moments where private pain and public reckoning collided. When she first spoke out about Harvey Weinstein, it wasn’t easy—this was a man who had built his career on fear and silence. She told the world what happened in that hotel room, how he had pressured her under the guise of a “business meeting,” and how her refusal set off a chain reaction she couldn’t see at the time.

After she said no, Weinstein didn’t just walk away—he used his power to quietly choke her career. Ashley later discovered he had spread lies about her to directors, deliberately blacklisting her from major roles. One of the clearest examples came when Peter Jackson revealed that she was blacklisted from The Lord of the Rings films because Weinstein’s company smeared her reputation. It wasn’t about her talent or ability—it was retaliation, a message to her and every other woman: defy me, and I’ll end you.

For years, she carried that loss without knowing the full extent of it, wondering why opportunities seemed to vanish. But when the scandal finally broke open and other women came forward, Ashley didn’t stay quiet. She became one of the first actresses to go on record, attaching her name to the stories that had long been whispered but never spoken aloud. That act of bravery helped open the floodgates for the MeToo movement, shifting it from rumor to undeniable truth.

The scandal between Ashley and Weinstein wasn’t just about one incident—it exposed the machinery of abuse in Hollywood, where men in power could control women’s livelihoods and futures with a single phone call. By speaking out, Ashley risked what little she had left in that world, but in doing so, she gave strength to a movement that would ripple far beyond film. Her story is proof of what happens when one woman breaks the silence: suddenly, the walls that seemed unshakable begin to crack.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

The ‘Women In World History’ social media project has been running on Instagram and Facebook since November 2016. Over the past 9 years, the curator has amassed a following of 58.1k followers on Instagram, as well as a jaw-dropping 289k followers over on Facebook. What’s more, the project has 2.6k fans on Threads.

According to the curator of ‘Women In World History,’ the project is a celebration of unforgettable women. They state that the past is full of influential individuals who are game-changers and who “made history in every manner possible and these just happened to be women.”

We’ve reached out to the curator to learn more about the project, and we’ll update the article as soon as we hear back from them.

#7

Rebecca Solnit attended a gathering in Aspen in 2008 where a wealthy older man discovered she was a writer and began lecturing her about an important recent book on photographer Eadweard Muybridge. He spoke with absolute certainty, steamrolling past her attempts to interject. Her friend had to practically shout that Solnit was the author before the information registered. And still, he kept talking.

Most people would dismiss this as one annoying encounter. Solnit saw something bigger—a pattern where male voices are automatically granted authority while women must fight to be heard even about their own expertise.

Her essay “Men Explain Things to Me” dissected this dynamic with devastating precision. She wasn’t complaining about rudeness but exposing how dismissal operates as a tool of power, training women to doubt their own knowledge and defer to unfounded male certainty.

The response was explosive. Women worldwide recognized their own experiences—being interrupted in boardrooms, corrected about their own research, lectured about their fields by men with superficial knowledge. Soon “mansplaining” emerged as shorthand, though Solnit never used that term. By naming the phenomenon, she made it visible and challengeable.

What elevated her analysis was connecting this to larger inequality. When women’s testimony isn’t believed, when their expertise is overridden, when their voices are discounted, they lose the ability to advocate for themselves from workplace negotiations to reporting crimes.

Solnit revealed everyday dismissals as symptoms of systematic devaluation spanning from tedious conversations to courtrooms where victims face skepticism. She validated what women had long sensed but been taught to minimize—that their frustration was reasonable response to being denied authority. She gave them permission to trust what they already knew.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#8

Did you know that when Ruth Bader Ginsburg walked into her Harvard Law classroom, she was one of only nine women among nearly five hundred men? Imagine the weight of those stares, the silence that greeted her when she spoke up, the constant need to prove she deserved to sit in that seat. She was brilliant, but brilliance alone wasn’t enough—she had to be relentless, disciplined, and unshakably confident in her worth at a time when women were often told their place was elsewhere. While her male classmates were assumed to belong, she had to justify her presence every single day. And still, she thrived. She studied late into the night, raised a young daughter, cared for her husband as he battled cancer, and managed to excel so greatly that she became the first woman to serve on the Harvard Law Review. Her path reminds us that the doors we walk through today weren’t always open. They were pushed, wedged, and sometimes kicked open by women like her, who refused to let the world decide the limits of their potential.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#9

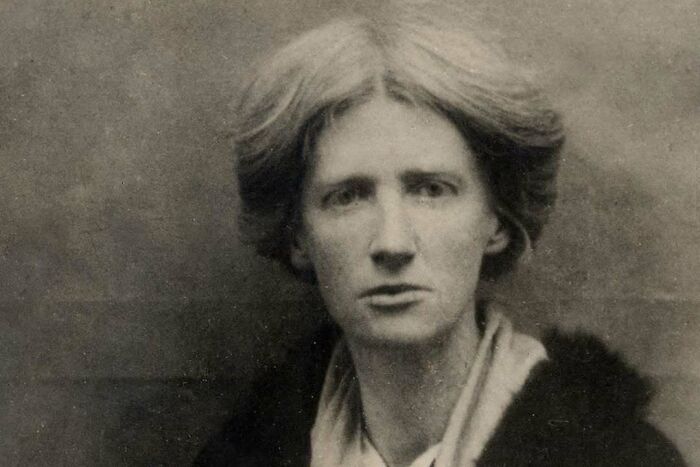

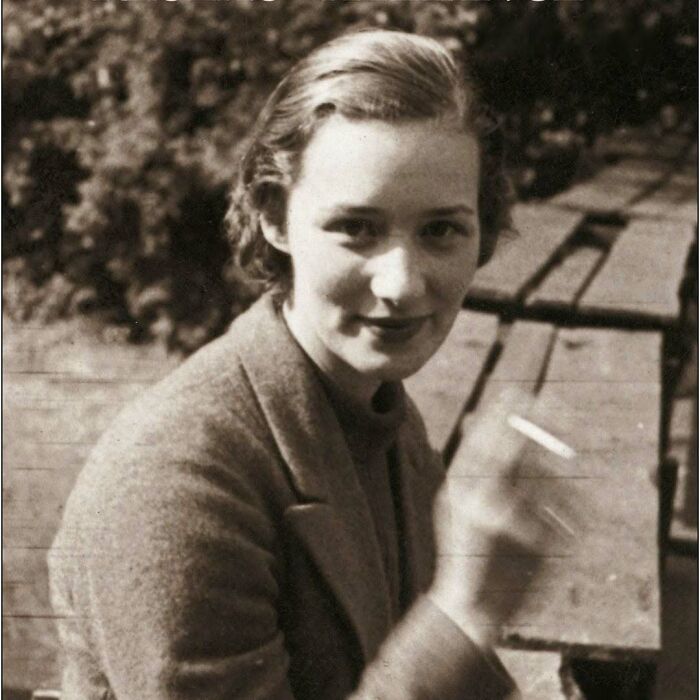

Charlotte Brontë’s life reads like one of her own gothic novels—filled with loneliness, imagination, and heartbreak. Born in 1816 in a bleak Yorkshire parsonage, she was the third of six children in a family that would become both legendary and doomed. Her mother died when she was five, and the sisters were sent to a harsh boarding school where two of them, Maria and Elizabeth, succumbed to tuberculosis. The trauma would later appear in Jane Eyre’s cruel Lowood School.

Back home on the windswept moors, the surviving Brontës—Charlotte, Emily, Anne, and their troubled brother Branwell—created vivid imaginary worlds and began to write. But in Victorian England, a woman’s words carried little weight. When Charlotte tried to publish her poems, she was told “literature cannot be the business of a woman.” So she and her sisters adopted male pseudonyms—Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell—and released their novels into the world.

Jane Eyre was an immediate sensation: bold, passionate, and shocking in its insistence that a woman’s soul was equal to a man’s. Just as success arrived, tragedy struck again. Within eleven months, Charlotte lost Branwell, Emily, and Anne—all to the same illness that had haunted their childhood. She wrote through her grief, clinging to purpose as her world emptied.

Eventually, she found companionship with her father’s curate, Arthur Bell Nicholls, and for the first time seemed to know contentment. But pregnancy brought exhaustion and sickness. In 1855, at just 38, she died before her child was born. Yet her story did not end there. Through Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë gave generations of women something radical: a heroine who thought, felt, and chose for herself. In death, she achieved what she had always longed for—freedom, and an immortal voice.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

The curator of ‘Women In World History’ isn’t the only person who is concerned with shining a light on what the past was really like.

During a previous in-depth interview, Bored Panda spoke with one internet user who inspired everyone to share examples of great women and female heroes who often get overlooked.

“I realized that I don’t know many famous women throughout history. Learning about how so many women who had thoughts or opinions on a subject were deemed crazy put into perspective how little I knew, and I wanted to educate myself more,” the internet user told us previously.

According to the internet user we previously interviewed, they were astonished by the popularity of the topic. It made them happy that so many people were curious, willing to challenge their biases, and willing to further educate themselves about women in history.

From their perspective, discrimination is the reason why women often get overlooked in history books.

#10

At just 19, Maria Schneider was betrayed by director Bernardo Bertolucci and Marlon Brando during filming of Last Tango in Paris. They deliberately kept her uninformed about specific details of a r**e scene, believing her genuine shock would create “authentic” reactions.

What we see on screen isn’t acting—it’s real distress from a teenager who was manipulated and deceived. Her humiliation was engineered by two powerful men who prioritized their artistic vision over her consent and dignity.

Schneider later said she felt “a little raped” by the experience. The trauma haunted her entire life while her pain was commodified and celebrated worldwide. She struggled with the violation of trust and how her suffering became entertainment.

Bertolucci didn’t express real remorse until 2013, two years after Schneider’s death in 2011. She never received the acknowledgment she deserved during her lifetime.

This remains one of cinema’s most disturbing examples of how women’s consent has been violated in the name of art. Maria Schneider’s story reminds us that behind every “controversial” scene is a real person who had to live with the consequences.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#11

In the summer of 1909, a 22-year-old homemaker named Alice Ramsey set out to do something utterly outrageous for her time: drive across the country. Not with her husband. Not with a mechanic. But with three other women—none of whom could drive. Her goal wasn’t to break speed records or prove technical prowess. It was to show that women belonged on the road just as much as men.

Back then, “roads” were more often than not little more than rutted trails, dust-choked tracks, or muddy messes barely passable by wagon. Maps were laughable. Gas stations were scarce. And the idea of a woman driving long distances was seen as a novelty—if not an outright act of rebellion. But that didn’t stop Alice. She loaded up a dark green Maxwell touring car and set off from New York City, determined to reach San Francisco.

The journey took 59 days. Along the way, they changed 11 tires, crossed treacherous terrain, drove through blinding rain and searing heat, and sometimes relied on telegraph poles for navigation. They were chased by men on horseback, stared at by stunned farmers, and even encountered Native American families still living on reservations. There were no hotel reservations. No GPS. No AAA.

Alice did all the driving. She also did most of the repairs. She had taken a car apart and put it back together before the trip, just in case. The other women—her two sisters-in-law and a friend—provided moral support, conversation, and an extra set of hands when needed. They were ladies of their time, wearing long skirts and wide-brimmed hats, but they were also bold enough to laugh in the face of convention.

When they rolled into San Francisco, they were met with astonishment. Newspapers across the country ran headlines about their feat. Men were impressed. Women were inspired. And Alice Ramsey became the first woman to drive coast-to-coast—a pioneer not only of the automobile age but of a new kind of female independence. Not flashy. Not angry. Just determined. Practical. And brave as hell.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#12

Admiral Linda Fagan made history in 2022 as the first woman to lead a U.S. military branch when she became Commandant of the Coast Guard. A supremely qualified cutterman, she broke barriers throughout her decades of service. Her command ended abruptly in January 2025 when she was relieved of duty by the new administration. While her dismissal was a stark reminder of the fragility of progress, her legacy as a pioneering leader remains unshakable. She proved, unequivocally, that a woman belongs at the helm.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

“They [women] weren’t in a position of power to safely promote their ideas on a certain topic or were told that they were crazy. I think the biggest reason would be that we just aren’t taught about their contributions and after so many decades and centuries, their names just get lost,” the internet user said, sharing their perspective about why so many women get sidelined.

However, while things may be improving on a societal level, with more recognition for women, there is also lots of room for improvement. “We’re still not where we need to be. Continuing to educate ourselves, as well as asking questions, will help pave a way for women to be equally recognized by men in the future,” the internet user told Bored Panda previously.

#13

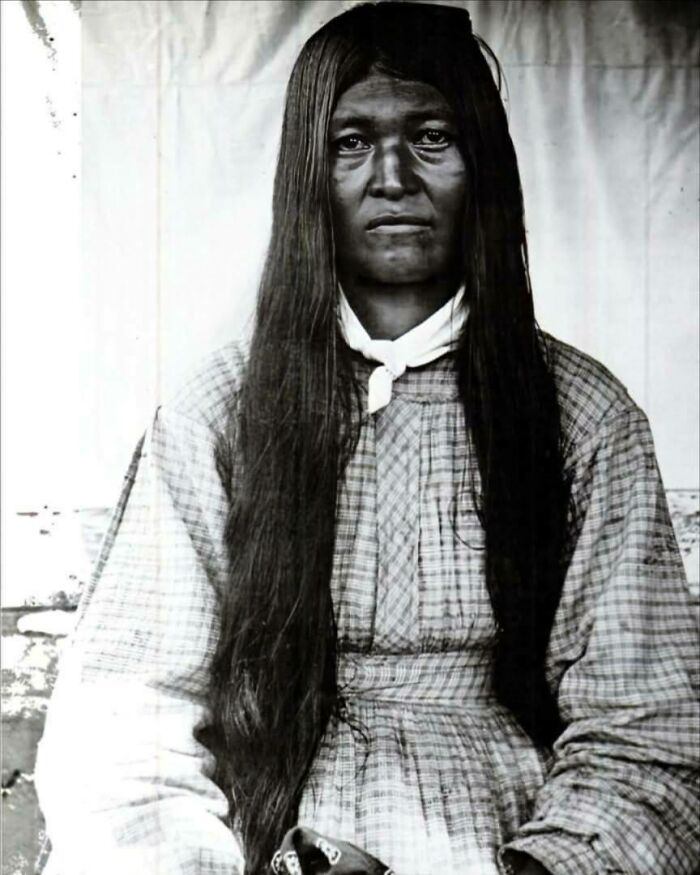

Imagine being given an instrument of your own culture’s suppression and using it to sing your people’s song back to the world. This was the quiet, powerful rebellion of Zitkála-Šá. As a child, she was taken from her Yankton Sioux community to a boarding school where the goal was to erase her identity. There, she was forced to learn European classical music. But instead of silencing her, this education gave her a new, unexpected voice.

She mastered the violin and piano, and with that skill, she composed *The Sun Dance Opera* in 1913. This was a radical act. At a time when the U.S. government had outlawed Native ceremonies, she used the most prestigious of European art forms—opera—to bring a sacred Sioux ritual to the stage. She wove together classical melodies with the rhythms and stories of her people, creating something entirely new yet deeply traditional.

Her music was more than performance; it was preservation and protest. She took the very tools meant to assimilate her and used them to carve out a permanent space for Indigenous culture. Beyond her compositions, she was a formidable writer and activist, fighting for citizenship and rights. Her life reminds us that our power often lies in transmuting our pain into creation. She took what was meant to break her and built a legacy, proving that our stories, once set to music, can never be erased.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#14

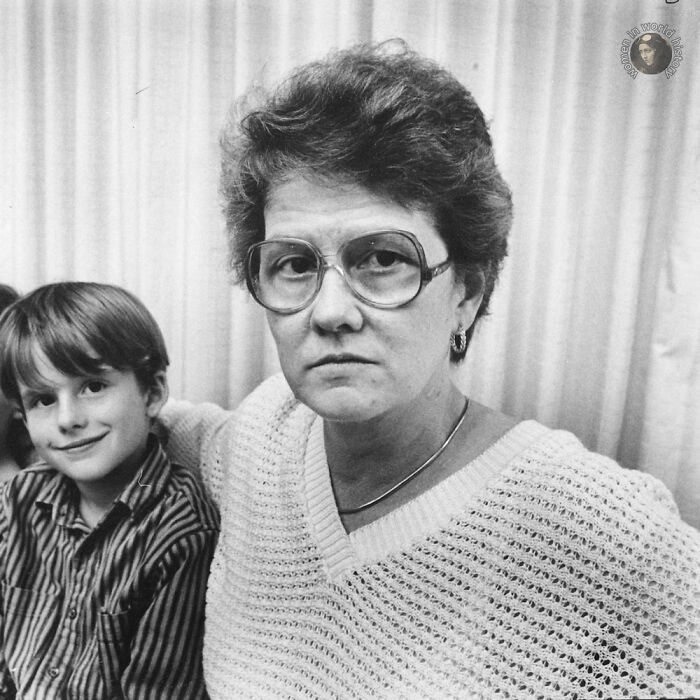

The Magdalene asylums, or Magdalene laundries, operated for centuries—from the 1700s all the way into the late 20th century—locking away generations of women under the guise of “moral redemption.” At their peak in the 19th and early 20th centuries, these institutions spread across Ireland, the UK, the U.S., Canada, and Australia, run primarily by Catholic orders but sometimes Protestant groups as well.

What’s especially chilling is how long they lasted. While many assume such oppressive systems belonged to the distant past, Ireland’s last Magdalene laundry didn’t close until 1996. That means women alive today—mothers, grandmothers, sisters—were imprisoned within living memory, forced to scrub floors, work in stifling laundries, and endure psychological and physical abuse, all while being told they were sinners in need of repentance.

For over 200 years, these institutions thrived because society allowed them to. Families, churches, and even governments colluded in sending “difficult” women away—unmarried mothers, abuse survivors, girls deemed too flirtatious, or even those with intellectual disabilities. Once inside, many were given new names, forbidden from speaking of their pasts, and treated as indentured servants. Some never left.

The legacy of the laundries is a stark reminder: oppression doesn’t always look like chains and dungeons. Sometimes, it wears the mask of charity, morality, and “for their own good.” And though the last laundry doors have closed, the echoes remain—in the unmarked graves of forgotten women, in the survivors still fighting for justice, and in the systems that still police women’s bodies and choices today.

We remember them. Not as fallen, but as forgotten—and demand that history never repeats its cruelty.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

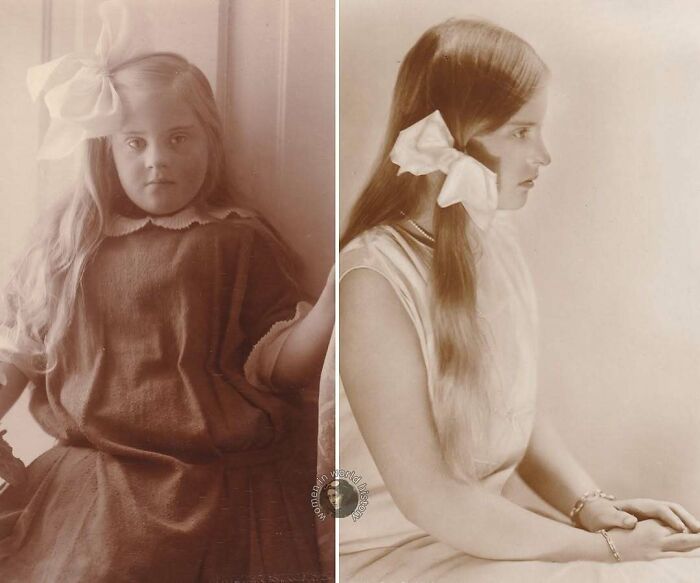

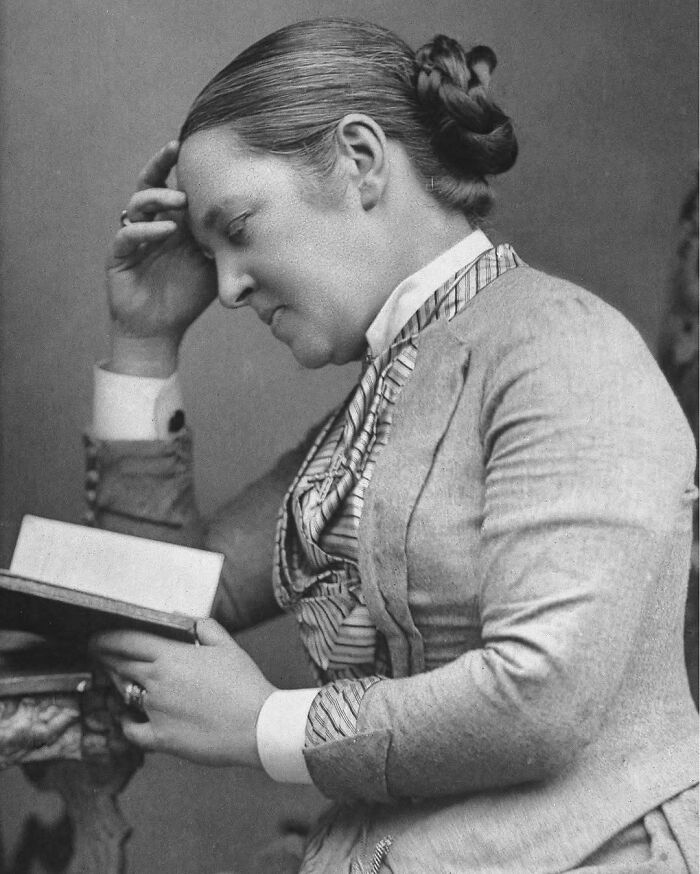

#15

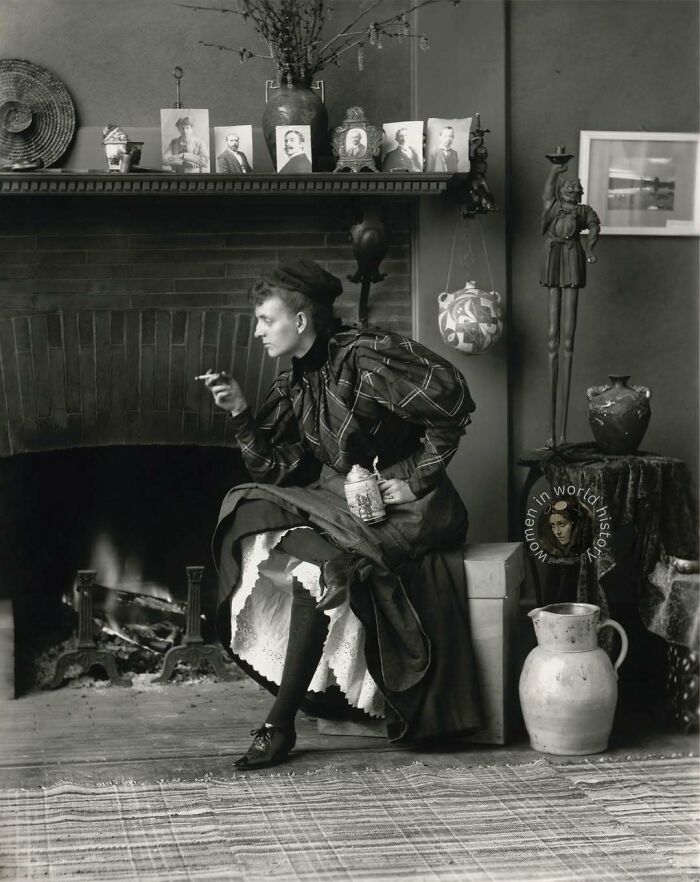

Georgina Ward, Countess of Dudley, lived a life that feels almost cinematic, filled with beauty, duty, resilience, and reinvention. Born in 1846, Georgina married William Ward, the 1st Earl of Dudley, when she was only eighteen. She was strikingly beautiful, quickly becoming one of the most admired women in Victorian society, and her life was steeped in wealth and social expectation. But beneath the gowns and glittering appearances, Georgina’s story is one of quiet strength and transformation.

After just a few years of marriage, her husband was paralyzed by a riding accident, leaving Georgina, still in her twenties, with the responsibility of caring for him and managing their extensive estates. She took on these duties with determination, moving from the role of a society beauty to a capable manager and devoted nurse. For over thirty years, she oversaw the vast Dudley properties and cared for her husband, never remarrying after his death despite being widowed in her prime.

What makes Georgina’s story particularly compelling is how she stepped beyond the narrow expectations of her era. She became deeply involved in charitable work, especially in nursing and hospital care, dedicating her time to improving the conditions of hospitals and supporting the nurses who worked within them. During the Boer War, she was actively engaged in supporting the troops, helping to organize medical care for soldiers, and later took part in organizing nursing services during World War I.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

Once you’re done reading through this list, we’d like to hear your thoughts in the comments, dear Pandas. Which of these stories captivated you the most? Were there any that you knew about from before? What female figures from history inspire you to this day?

What do you do to develop a deeper understanding of human history? What historical periods fascinate you the most? Let us know!

#16

Anna Akhmatova lived through some of the darkest years of Russia’s history, and her poetry carried the weight of that suffering with a kind of quiet, unyielding dignity. Born in 1889, she came of age in a time of revolution and upheaval, and from the beginning her poems had a rare ability to distill private emotion into something universal. She wrote of love and loss with clarity and restraint, and early in her career, her voice was celebrated for its intimacy and honesty. But as the decades unfolded, her role shifted from being a lyric poet to something much heavier—she became a witness.

The years of Stalinist terror touched every part of her life. Friends were arrested or executed, her first husband was shot, and her beloved son Lev was imprisoned more than once. She spent long hours standing in prison lines, waiting for news, surrounded by women like her—mothers, wives, sisters—each of them carrying unbearable fear and grief. From those experiences came Requiem, a cycle of poems that gave voice to their collective anguish. It was never published in her lifetime in Russia; instead, it was whispered from memory, passed from one woman to another like contraband truth.

Akhmatova herself was silenced, censored, and watched, but she refused exile. She stayed in Russia when many others left, believing her place was among her people, to endure with them. She once wrote, “I was with my people then, where my people, unfortunately, were.” That choice came at a cost, but it also defined her legacy.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

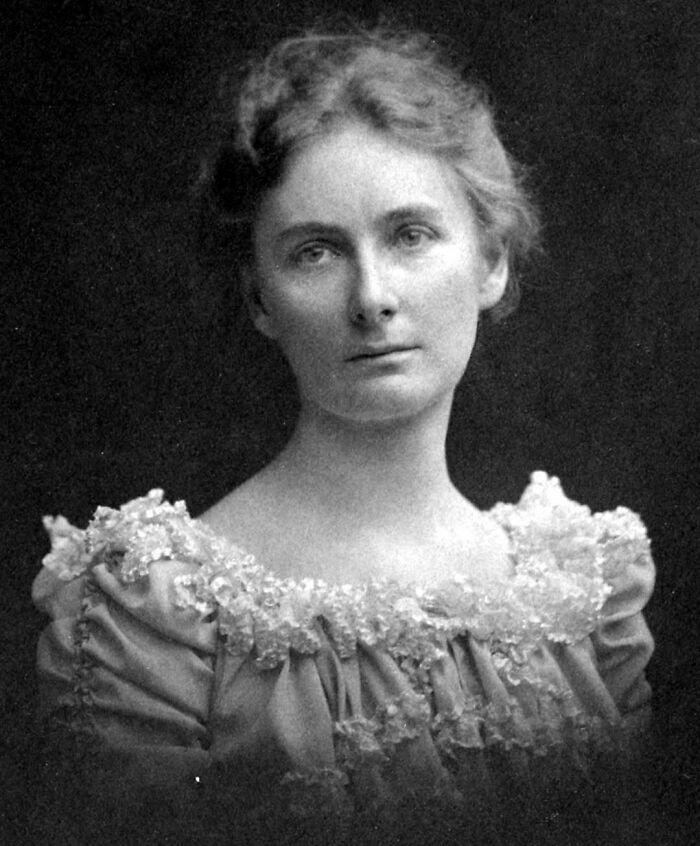

#17

Elizabeth Packard’s story is both heartbreaking and deeply inspiring. In 1860, after years of marriage and raising six children, her husband used the law to have her committed to an insane asylum. His reason wasn’t violence or instability—it was that she dared to think differently. Elizabeth questioned his strict Calvinist views and voiced her own independent beliefs, and at that time in Illinois, a husband could institutionalize his wife without any proof, without trial, and without her consent.

Inside the asylum, Elizabeth quickly realized that many of the women around her weren’t “insane” at all. They were simply inconvenient—wives who resisted, daughters who disobeyed, women who challenged the narrow roles forced upon them. Rather than breaking her spirit, the experience sharpened her resolve. She observed everything, took careful notes, and planned for the day she could share the truth.

After three years, she managed to get her case before a court. Her husband tried to paint her as unstable, but Elizabeth stood her ground. She spoke clearly, defended her right to her own thoughts, and won her freedom. The moment was more than personal vindication—it was a public statement that women were not property and their voices could not be dismissed as madness.

But she didn’t stop there. Elizabeth took her fight further, writing books about her ordeal and lobbying for changes in the law. Her persistence led to reforms that gave women greater protection from wrongful confinement and expanded their rights within marriage.

Her courage came at a time when defying a husband could cost a woman everything—her children, her reputation, even her freedom. Yet she chose truth over silence. Elizabeth Packard turned her personal injustice into a movement that made it harder for others to be silenced the way she was.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#18

Sylvia Earle, the 90 year old American marine biologist, is often called “Her Deepness,” which is just the perfect nickname. It speaks to a lifetime of diving deep, not just into the ocean, but into her purpose. Imagine, in the 1970s, strapping into a bulky suit and diving to the ocean floor in a way no human had before. She wasn’t just visiting; she was making the deep sea her workplace, her laboratory, her sanctuary. At a time when the world was looking up at the stars, Sylvia was urging us to look down, into the planet’s own blue heart.

Her story isn’t just one of scientific firsts—though there are plenty, like being the first woman to serve as the chief scientist at NOAA. It’s a story about a different kind of strength. It’s the strength that comes from curiosity, from a deep and abiding love for the living world. She fell in love with marine algae, for goodness’ sake—the lush, underwater meadows that are the foundation of life in the sea. She saw the magic in what others might overlook, and in doing so, she redefined what it meant to be an explorer.

What’s so inspiring is how she’s channeled that lifelong intimacy with the ocean into a fierce, maternal protectiveness. She didn’t just study the sea; she learned its language, its rhythms, its distress signals. And when she saw it suffering, she didn’t just write papers. She founded Mission Blue, an organization with a vision that feels both audacious and deeply intuitive: to create “Hope Spots” all over the world.

Think of them like national parks, but in the ocean. These are places that are critical to the health of the whole system, and she’s fighting to have them recognized and protected. It’s a vision that comes from a place of hope, not fear. It’s the kind of idea that emerges when you’ve spent your life not as a tourist in nature, but as a part of it.

Sylvia’s work reminds us that the call to explore, to understand, and to protect isn’t reserved for others. It’s a call that can start with that same feeling we get at the water’s edge—that sense of wonder.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#19

This is a very poignant image from WWI – Red Cross nurses played such a crucial role in providing comfort to dying soldiers, often serving as the last human connection these men had. The act of recording final words was both a practical necessity (for families back home) and a deeply compassionate gesture.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#20

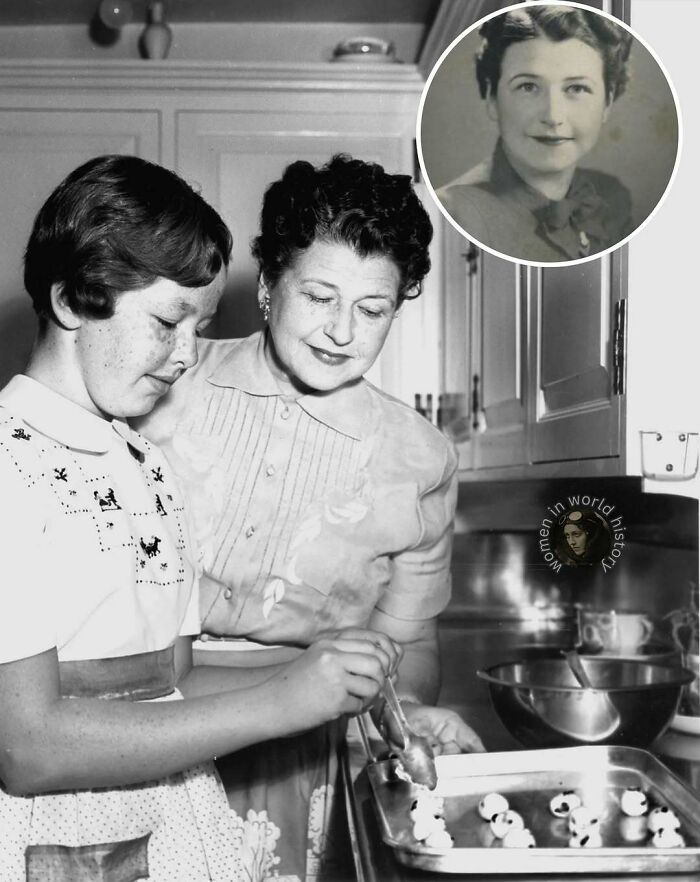

Kirk Douglas’s mother, Bryna Sanglel (later Bryna Demsky), lived an extraordinary life that rarely gets the attention it deserves. Born around 1884 in what is now Belarus, she was a Jewish woman from a poor shtetl who knew only hardship and survival. She married Herschel “Harry” Demsky, a ragman, and together they fled the brutal poverty and antisemitic violence of Eastern Europe for America in the early 1900s. Like millions of immigrants of that era, they arrived with nothing—no money, no English, just hope.

They settled in Amsterdam, New York, where Harry worked collecting scrap metal and rags from the streets. The family lived in crushing poverty, often in cramped, drafty rooms without heat or running water. Bryna gave birth to seven children, including the boy who would become Kirk Douglas, then called Issur Danielovitch Demsky. She raised them with fierce love and resilience, making soup from bones and bread crusts, washing clothes by hand, and pushing her children to believe they were destined for more than the world told them they were worth.

Kirk often spoke of her as the emotional center of his life—the one who taught him pride and persistence. He remembered how she went without food so her children could eat, how she saved pennies for books, and how, despite never learning to read or write in English, she carried herself with quiet dignity. When Kirk became a Hollywood star, he named his production company **Bryna Productions** after her—a way to immortalize the woman whose strength had carried him from a dirt-poor boyhood to international fame.

Bryna never lived to see the full extent of her son’s success; she died in 1958. But her story is the quintessential immigrant mother’s tale—one of endurance, sacrifice, and an unshakable belief that life could be better for her children. Kirk often said he owed everything to her. She was the real foundation beneath the glamour, the heart of the story that began long before Hollywood ever knew his name.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#21

She wore robes like a medieval priestess, draped in bold jewels and towering headpieces that made her impossible to ignore. Edith Sitwell wasn’t just a poet—she was a statement, a woman who refused to shrink to fit the world’s narrow ideas of how a woman (or a writer) should look, act, or create.

Born into aristocracy but rejecting its stifling conventions, Sitwell became a fierce champion of avant-garde art and poetry. She mentored troubled geniuses like Dylan Thomas, clashed with the literary elite (her legendary feud with Noël Coward is pure drama), and wrote verses that were as daring as her fashion.

Her life was a masterclass in unapologetic self-expression. She turned her pain—loneliness, a difficult family, critics who mocked her—into art that was strange, beautiful, and wholly her own.

“I am not eccentric. It’s just that I am more alive than most people.” — Edith Sitwell

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#22

In the soot-streaked corners of Victorian London, there were women whose pain the city refused to name, so it gave them one: “Crawlers.” These were not faceless beggars or nameless poor. They were women with stories—mothers who had buried children, widows left behind by war or disease, wives discarded like worn cloth. Hunger had hollowed out their strength until standing became a luxury. So they crawled.

They crawled between charity houses and soup lines. Crawled to avoid the jeering eyes of strangers. Crawled because the world would not give them space to walk with dignity. They wore rags that clung to their bones, slept in alleyways or under bridges, often with a child pressed to their chest—if they were lucky enough to have one still breathing. Work, when they could get it, was a patchwork of underpaid labor: hand-washing sheets for pennies, hemming until their fingers bled, selling matches in the cold. And when none of that was enough, they traded their bodies for coins. Not for vice. For survival.

They were dismissed as shameful, filthy, or immoral. But look closer, and you’ll see the truth: these women were warriors of endurance. Their crawl was not weakness—it was resistance. A body kept alive by will alone. A mother’s instinct defying the grave. They didn’t want pity. They wanted bread. Shelter. A chance.

And though the city tried to look away, their presence lingered in doorways and under gaslights, daring it to see. To acknowledge that progress built on crushed women is not progress—it is cruelty. These women mattered. Every shiver. Every tear. Every inch forward on the cold, unforgiving ground.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

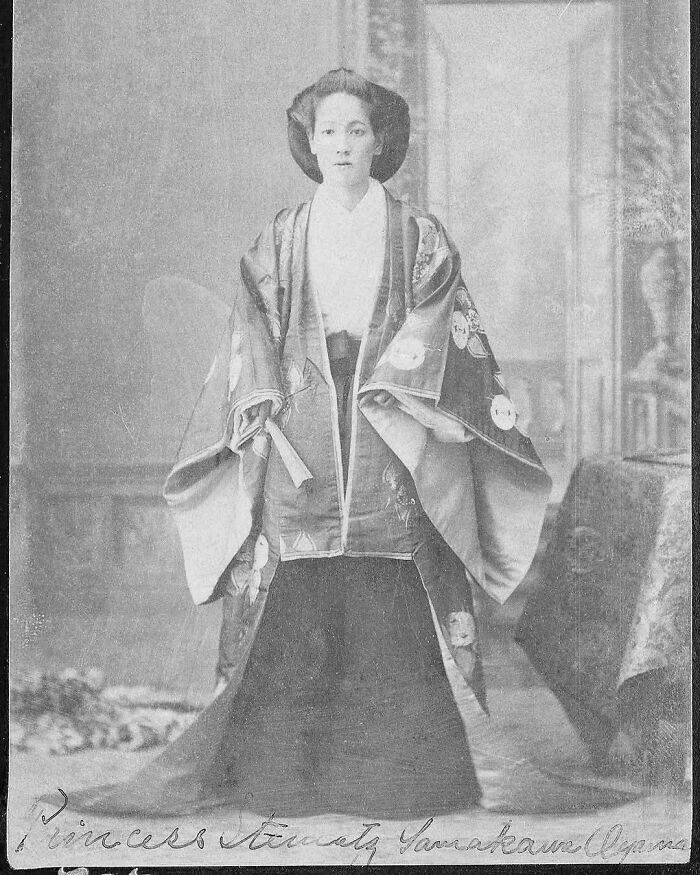

#23

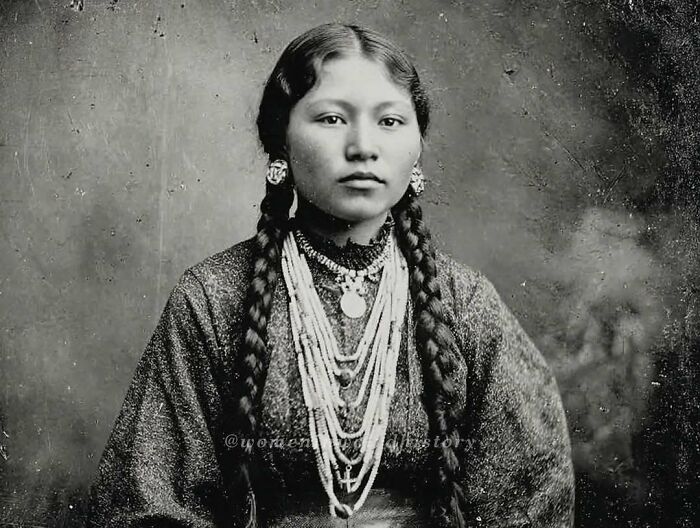

At just 11 years old, Yamakawa Sutematsu was taken from her family in Japan and sent across the ocean to the United States as part of a government mission to learn Western ways. She arrived not knowing English, not even able to read or write in her own language fully, and was thrust into a world of heavy dresses, new foods, and a culture that often saw her as a curiosity. But Sutematsu wasn’t there to simply observe. She became the first Japanese woman to graduate from an American college, finishing at Vassar in 1882, earning respect from peers who recognized her intelligence, resilience, and quiet but clear determination.

She could have chosen a comfortable life in the U.S. after graduation, but she returned to Japan, where the Meiji era was transforming society at a rapid pace. Marriage shifted her status in ways that might surprise many: she became a princess by marrying into the Kazoku aristocracy, taking the name Oyama Sutematsu. Yet she didn’t let her title or the restrictive norms of the time keep her from using her education for a purpose greater than herself.

Sutematsu became a champion for women’s education in Japan, helping to found institutions that gave young Japanese women a chance to learn in a system that had long denied them opportunities beyond domestic expectations. She encouraged girls to learn English, to pursue studies beyond what was expected, and to see themselves as worthy of education, independence, and purpose.

She also worked tirelessly during the Russo-Japanese War, organizing nurses and relief efforts, defying the stereotype of the silent, passive princess. She moved between worlds — the polite, rigid world of the Japanese court and the practical, reform-minded spaces of education and charity — using her social position to elevate the lives of other women while remaining true to the ideals of service she had cultivated during her years in the United States.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#24

Salome Alexandra, Queen of Judea, was a remarkable figure in a time when women were often marginalized. After the death of her husband, King Alexander Jannaeus, she faced dismissal from those who viewed her as weak and incapable of leading. But rather than succumb to their doubts, she stepped into her role with a blend of wisdom and strength that would define her reign.

Salome’s leadership was characterized by a commitment to stability in a tumultuous political landscape. She skillfully navigated the complex relationships between various factions, fostering peace during her time on the throne. But her most profound legacy lay in her dedication to education, particularly for women. At a time when female voices were rarely heard, she championed the expansion of Jewish education, ensuring that women had access to knowledge and could participate in the cultural and religious life of their communities.

Her actions inspired a generation of women to seek education and empowerment, challenging societal norms that sought to confine them. Salome’s reign marked a significant shift in the perception of women’s roles in Judean society, proving that they could be both leaders and scholars.

Yet, despite her successes, Salome faced relentless opposition from those who could not accept a woman in power. As her health declined, political rivals grew bolder, seizing the opportunity to undermine her authority. After her death, the very progress she fought for began to erode, and the educational initiatives she championed faced setbacks. Her tragic ending serves as a reminder of the fragility of hard-won advancements.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#25

Muriel Gardner transformed from wealthy American heiress to underground resistance fighter in 1930s Vienna. Born into Chicago’s meat-packing elite with a fortune worth over $90 million today, she initially moved to Austria to study psychoanalysis with Freud’s circle.

When fascists rose to power, Gardner witnessed a funeral procession for anti-fascist fighters that sparked her moral awakening. “They could not cancel out the feelings building up within me,” she wrote, “indignation, anger and an imperative need to continue the struggle.” Operating under the codename “Mary,” she became the only known American woman aiding the Austrian Resistance.

Gardner used her wealth strategically—purchasing safe houses, false documents, and bribes while her American passport provided crucial protection. She transformed her Vienna apartment into a clandestine waystation, helping thousands of Jews and anti-fascists escape Nazi persecution despite extraordinary personal risk.

Her story defies expectations about who becomes a resistance fighter. With every reason to flee to American safety, she chose to stay and fight, proving that moral courage can emerge from unexpected places. The lonely heiress seeking therapy became one of Austria’s most effective underground operators, using her inherited fortune not for luxury but to save lives during humanity’s darkest hours.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#26

In the summer of 1967, a young Filipina actress named Maggie de la Riva walked into a courtroom in Quezon City and did something that few women of her time—or any time—have ever done with such courage. She pointed her finger at the four men who had kidnapped and gang-raped her just five days earlier. They were not strangers from dark alleys. They were sons of powerful, wealthy families, men who expected to walk free. The room fell silent as she raised her arm, showing bruises on her skin. “Do you remember these?” she asked one of them. Her voice didn’t tremble. Theirs did.

Maggie had been a rising star in Philippine cinema—beautiful, educated, and ambitious. Her fame didn’t protect her. When the men abducted her outside her home, they assumed she would stay quiet, that shame and fear would keep her silent, as it had silenced so many women before her. But Maggie refused to disappear behind the stigma that so often punishes survivors instead of perpetrators. She chose to face her attackers in public, under the harsh glare of cameras, knowing that society would question her morality before it questioned theirs.

The trial became one of the most sensational and divisive in Philippine history. People whispered her name, debated her virtue, and speculated about whether she had “provoked” what happened to her. But Maggie never wavered. She sat in that courtroom every day, her presence a statement that what had been done to her would not be buried in secrecy or shame. The men smirked, joked, and relied on their families’ influence. Yet her testimony was unwavering, precise, and devastating. She turned her trauma into undeniable evidence.

In the end, justice came—rare and imperfect, but real. The four men were found guilty and sentenced to death, a shocking outcome in a country where the powerful were often untouchable. Maggie’s bravery broke through the myth that wealth could buy impunity.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#27

In 1894, Madeline Pollard shocked the nation by suing Congressman William C. P. Breckinridge for breaking his promise to marry her after years of a secret affair. Despite public shaming and fierce attacks on her character, she testified with clarity and courage, exposing his lies and hypocrisy. The jury sided with her, ending his political career. At a time when women had few legal rights, Pollard’s bold stand was a rare public demand for dignity and accountability.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#28

Katherine Swynford entered English history quietly, first as a young girl brought to England when her father followed Queen Philippa from Hainault, then as a lady-in-waiting. She married Hugh Swynford, a knight in John of Gaunt’s service, and lived the life expected of a minor noblewoman, managing households, bearing children, keeping the daily fabric of life stitched together while her husband was away fighting. She was widowed young, with children to raise, but it was in this period that her life shifted from duty to a story of deep, complicated love.

John of Gaunt was one of the most powerful men in England, the son of King Edward III, and his marriage to Katherine’s friend Blanche tied Katherine’s life to his household. After Blanche’s death, Katherine and John’s connection transformed into an affair that scandalized the English court. It was a relationship that endured decades, despite harsh public judgment and political tides shifting under their feet. She was his mistress openly, and while this made her the target of moral outrage, it was also a testament to the strength of her presence in his life, the loyalty they held for each other, and the endurance of their love against the expectations of their time.

Later, in a moment that no one could have predicted for the daughter of a knight and herald, John of Gaunt married Katherine, legitimizing their children and lifting her from mistress to Duchess of Lancaster. It was a rare and almost shocking move, allowing Katherine to end her life not in scandal, but in legitimacy and respect. Her children, the Beauforts, would become key players in England’s future, directly influencing the line that would become the Tudor dynasty.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#29

Imagine the horror: Lying on a beach, surrounded by the bodies of your fellow nurses, as the sound of gunfire fades and the waves wash over you. This was the reality for Vivian Bullwinkel, an Australian nurse and one of the bravest women in history.

During World War II, after the fall of Singapore, Vivian and 21 other nurses were marched into the sea on Bangka Island—and executed by Japanese soldiers. Miraculously, Vivian was shot but survived by playing dead, clinging to life as the tide carried her to shore.

But her courage didn’t end there. Despite her wounds, she hid in the jungle for 12 days before surrendering—only to endure three and a half years as a prisoner of war. Even in the brutal conditions of the camp, she continued nursing in secret, saving lives while facing starvation, disease, and cruelty.

After liberation, she became the sole survivor to testify about the massacre—ensuring the world would never forget the atrocities committed. She later dedicated her life to nursing and veterans’ welfare, proving that resilience and compassion can triumph over even the darkest evil.

Vivian’s story is a testament to the strength of women—the kind that refuses to be broken, no matter the cost. Let’s honor her memory and remember: We are capable of so much more than we know.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#30

She didn’t learn to read until age nine. Born to a strict, insular farm family in Depression-era North Dakota, Mary Sherman Morgan wasn’t even sent to school until the local authorities intervened. But once she got a taste of education, she devoured it. A scholarship took her to college in Ohio—an extraordinary leap for a young woman from such isolated beginnings—but with World War II raging, she left school early to contribute to the war effort. Her chemistry background landed her at a munitions plant, where she helped develop explosives for military use.

After the war, she applied to North American Aviation, a defense contractor where she was placed—not in secretarial work, like most women at the time—but in the engineering department. She was the only woman in the division, and the only one without a degree. Still, her coworkers quickly realized her mind was extraordinary. When America was desperate to catch up in the space race, it was Morgan they turned to with an urgent challenge: invent a rocket fuel strong enough to send a satellite into orbit.

There was a catch. The rocket’s engine had already been designed without knowing what kind of fuel it would require. This meant Morgan had to reverse-engineer a brand-new propellant—an unheard-of feat, especially with the high stakes of beating the Soviets to space. Under intense pressure, and with limited resources, Morgan created a fuel blend she called “Bagel.” It used LOX—liquid oxygen—as the oxidizer. Naturally, she thought it would be poetic to say the rocket would run on “Bagel and LOX.” But military brass didn’t appreciate the pun. The name “hydyne” was chosen instead.

Her invention worked. On January 31, 1958, Explorer I became the first successful U.S. satellite to reach orbit. The launch marked a major turning point in the Cold War-era space race. But while the moment made headlines, Mary’s name did not. In fact, her work remained largely classified, and her contributions were almost completely lost to history.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#31

Cynthia Ann Parker was just a child, around nine years old, when Comanche warriors raided her family’s settlement in Texas. She was taken from everything she knew, but within the Comanche community, she found another life. She was adopted, given the name Naduah, and raised as one of their own. She learned their language, lived their rhythms, and became part of their world in a way that was full and complete. She grew up, married the Comanche chief Peta Nocona, and became a mother to three children, including Quanah Parker, who would later become a renowned Comanche leader.

Twenty-four years after her capture, Texas Rangers stormed her village and found her, now a mother, living the life she knew and loved. They took her back, calling it a “rescue,” but for Cynthia Ann, it was a loss. She was torn from her husband, from her children, from the land and people who had become her entire world, and brought back into a society that expected her to pick up where she left off as a nine-year-old child. She did not know the English language anymore, and the customs felt foreign to her. She tried repeatedly to return to her Comanche family, grieving the separation from her children and her identity.

Cynthia Ann spent the rest of her life longing for what had been taken from her a second time. Her story is a reminder of the complexity of identity, of the different forms that family and belonging can take, and of the silent grief that many women have endured when they are denied the right to choose where they belong and who they wish to be. It is also a reminder of the many stories of women whose lives have been reshaped by conflict and whose voices often remain unheard in the larger narratives of history.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#32

When Lillian Hellman was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee, she knew the stakes. Careers were being destroyed overnight, friends turned against each other, and the pressure to conform was suffocating. But when asked to betray her colleagues and “name names,” she refused. Her words — “I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year’s fashions” — weren’t just a defiant statement, they were a lifeline for anyone watching who still believed in integrity over fear.

It was an act of courage that cost her dearly: she was blacklisted, her reputation attacked, her career derailed. Yet she stood by her principles, even when silence or compliance would have been far easier. In a time when conformity promised safety, she chose conscience. That decision turned her into more than a playwright; it made her a moral voice in one of America’s darkest political chapters.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#33

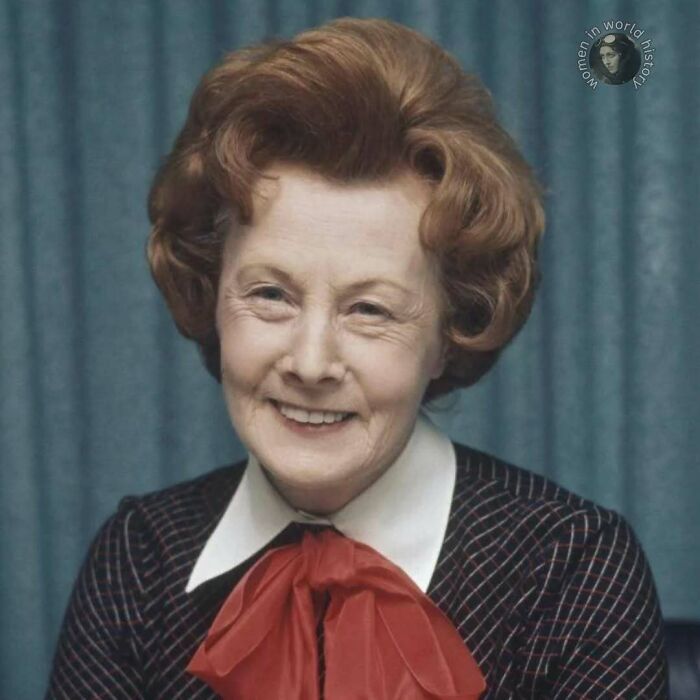

She was one of the most formidable women in British politics, known not just for her sharp intellect but for her fierce sense of justice. Barbara Castle spent decades fighting within a system that was never built for women like her—outspoken, working-class, and absolutely unwilling to be ignored.

She entered Parliament in 1945, one of only 24 women elected that year, and quickly made herself impossible to overlook. With her signature red hair and fiery speeches, she took on issues that others wouldn’t touch. She championed workers’ rights, improved conditions for the disabled, introduced seatbelt laws, and took on the powerful male unions who often dismissed her. But it was in 1970 that she pushed through one of her most lasting legacies: the Equal Pay Act.

At the time, women in Britain could legally be paid less than men for the same work—something often accepted as the norm. Castle had watched the Dagenham women strike in 1968, walking off their sewing machines at the Ford plant to demand equal treatment. While others tried to calm the situation or quietly dismiss it, Barbara listened. And then she acted. She pushed legislation through Parliament that made it illegal to pay women less simply because of their gender—a radical idea at the time, and one that faced enormous resistance.

But she didn’t stop there. As Secretary of State for Social Services, she introduced family allowances and a more generous pension system for women. She argued that women shouldn’t have to choose between motherhood and financial security, and that social policy had to reflect women’s realities, not just men’s expectations.

Barbara Castle wasn’t always liked. She didn’t care to be. She was often called strident, difficult, even dangerous. But to many women, especially working-class women, she was a lifeline—a rare figure in power who understood their struggles because she had lived them too.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#34

It’s a story that feels both astonishing and deeply relatable. In 1959, a woman named Arlene Pieper Stine did something extraordinary, almost on a whim. She was a 29-year-old mother living in Colorado, and she’d taken up running to get in shape. Not for glory, not to break barriers, but for herself. That simple, personal motivation led her to the starting line of what was then, and still is now, one of the most grueling races imaginable: the Pikes Peak Marathon.

The course goes from the streets of Manitou Springs straight up to the 14,115-foot summit of Pikes Peak, and then all the way back down. The air gets thin, the terrain is brutal, and it’s a test of sheer will for anyone who attempts it. And there was Arlene, running alongside the men, with no real precedent for what she was about to do. There was no fanfare, no special category for her. She was just a woman, running.

And she finished. She crossed that finish line, her daughter waiting for her, having accomplished this incredible physical feat. Then, she simply went home. She went back to her life, to raising her family, to her work as a physical therapist. The race became a wonderful memory, a story to tell now and then about that time she ran up a mountain. But what she never knew, for over fifty years, was that she had quietly, and without any intention, made history. She was the first woman ever officially recorded as finishing a marathon in the United States.

Can you even imagine? To hold a piece of history within you, a secret even to yourself, for half a century? It’s a thought that’s both thrilling and humbling. She wasn’t running for a place in the record books; she was running for the pure, personal challenge of it. There’s a profound beauty in that. Her achievement wasn’t about beating others; it was about answering a call to see what her own body and spirit could do.

It wasn’t until 2009 that a historian, digging through old race results, discovered the truth and tracked her down. After fifty years, Arlene learned that her personal triumph was also a landmark moment for women in sports.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#35

Imagine needing your father’s or your husband’s permission just to get a credit card. That was the reality for women not so long ago. Your financial life wasn’t truly your own. But in 1974, something quietly revolutionary happened. A new law made it illegal to deny someone credit based on their gender.

Just like that, the need for a man’s signature vanished. It was more than just a piece of plastic; it was a key. A key to an apartment lease you could sign yourself, to a car loan for the vehicle that would get you to your new job, to building a future with your own name on it. It was the freedom to build a life, not as someone’s daughter or wife, but as your own complete person. It was the first, real step toward financial independence, the moment we could finally start writing our own stories.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#36

She was barely out of her teens when the glittering salons of #Europe began whispering her name. In 1890, Clara Ward, a young American heiress from Detroit, had married into one of Belgium’s oldest noble families, becoming the Princess of Caraman-Chimay. It was the kind of fairy tale society loved—a beautiful young woman of immense fortune marrying a European prince. She wore diamonds like they were a second skin, sat for celebrated artists, and turned heads wherever she went. But Clara was not made to be ornamental. She had a wildness in her, a restless spirit that refused to be contained by gilded walls and rigid protocol.

In 1896, that spirit broke loose in the most spectacular way. At a train station in Paris, she encountered Rigo, a Hungarian Roma violinist whose music seemed to set her very soul alight. Their attraction was instant and consuming. Soon she had abandoned her palace, her title, and her husband, scandalizing high society by running off with him. The newspapers were merciless, and her name became a byword for impropriety. Yet Clara did not hide. She traveled with Rigo across Europe, sometimes performing alongside him, sometimes simply reveling in a life of freedom that had been denied her in her royal marriage.

The glamour she once wore for duty now became a form of defiance. She dined in cafés instead of palaces, appeared in public with her lover draped on her arm, and turned her notoriety into a kind of currency. Society might have exiled her, but she understood something they did not—there was a different kind of power in refusing to be respectable. Clara’s choices cost her dearly in reputation, and her life would be marked by restlessness and reinvention. Yet, to the end, she lived on her own terms, leaving behind a legacy not of dutiful compliance but of audacious self-determination.

Her story was a cautionary tale to some, a thrilling romance to others, but above all it was proof that not all princesses stay in their towers. Some set them ablaze just to see what lies beyond the smoke.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#37

At just 21, Andrée Borrel left everything she knew in France to fight back against the Nazis who had overrun her country. She joined the French Resistance, taking on the quiet, relentless work of guiding downed Allied pilots to safety, ferrying weapons, and gathering intelligence under constant threat of arrest or execution. But it wasn’t enough for Andrée to simply resist; she wanted to strike harder.

She trained in Britain with the Special Operations Executive (SOE), learning how to parachute into enemy territory, handle explosives, and move through occupied streets unnoticed. She was one of the first female agents to parachute back into France, dropping under cover of night to help build sabotage networks in preparation for the Allied invasion. Andrée didn’t hesitate to blow up power lines, disrupt railways, or help plan attacks against German supply routes, even when it meant risking capture at every turn.

She lived with the knowledge that women in resistance networks faced not only torture and execution if caught but also gendered violence from their captors. Still, she pressed on, hiding in safe houses, moving under curfew, and training others in sabotage techniques. She was described by those who worked with her as courageous, calm under pressure, and fiercely dedicated to her mission.

Eventually, Andrée was betrayed and arrested by the Gestapo. Even under brutal interrogation, she refused to give up her comrades or her mission. She was executed at Ravensbrück concentration camp at just 24, her last moments marked by the same bravery that had defined her brief but extraordinary life.

Andrée Borrel’s story is a reminder of the women who stepped into war zones not because they had to, but because they chose to fight for freedom, refusing to be passive observers of injustice. Her legacy, like that of so many women in the resistance, shows that courage is not the absence of fear but the choice to act despite it, even when the stakes are life and death.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#38

Eglantyne Jebb was a woman ahead of her time, driven by fierce compassion and moral clarity. Born into privilege in 1876, she could have easily chosen a life of comfort and quiet charity. Instead, she dedicated herself to confronting the harsh realities faced by children in the aftermath of World War I—many of whom were starving, orphaned, and forgotten. Jebb believed that no child, no matter their nationality or circumstance, should suffer because of the failures of adults.

In 1919, she founded Save the Children, an organization built not on pity but on the belief in every child’s right to survival, protection, and opportunity. Her activism was radical for its time. She was arrested for distributing leaflets protesting the British blockade that kept food from reaching children in postwar Europe, but her conviction only deepened her resolve. She didn’t just want to feed children—she wanted to give them a voice in a world that treated them as invisible.

A few years later, Jebb drafted the first-ever Declaration of the Rights of the Child, a bold document that would lay the groundwork for the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child decades later. It stated that children had the right to grow, learn, and be protected regardless of race, religion, or circumstance—a revolutionary idea in an age when children were often viewed as extensions of their parents, not as individuals with their own rights.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#39

When Britain stood on the brink of war in 1939, the country faced a terrifying truth—if supply lines were cut, it could starve. To survive, Britain had to feed itself, and to do that, it needed hands to work the land. With so many men called to fight, the government turned to women. Thus, the Women’s Land Army was born, and thousands of “Land Girls” answered the call.

They came from farms and factories, from London flats and northern mill towns—some had never even seen a cow before. They traded dresses for dungarees and lipstick for mud, working from dawn till dusk ploughing fields, milking cows, and harvesting crops. They repaired machinery, stacked hay bales, and dug ditches in all weather. It was backbreaking, filthy, and often lonely work—but it was vital. Every loaf of bread, every sack of potatoes, every egg they produced helped keep Britain alive while ships at sea were being sunk by enemy U-boats.

By 1944, more than 80,000 women were serving in the Land Army under Lady Denman’s leadership. Many lived in hostels or barns, facing skepticism and sometimes ridicule from the very farmers they’d come to help. Yet over time, they earned respect the hard way—through sheer grit. Their laughter, their songs, and their determination became part of Britain’s rural rhythm.

When the war ended, there were no parades for them. Most simply returned home, quietly resuming the lives they had paused to serve their country. The Women’s Land Army was officially disbanded in 1949, but its legacy endured. These women fed a nation under siege, proved that strength has no gender, and changed forever the way Britain saw its daughters.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#40

Ann Hopkins never set out to become a symbol of change, but her fight reshaped the way women—and later LGBTQ people—are treated in the workplace. At Price Waterhouse, she was brilliant, successful, and profitable for the firm. By every business measure, she deserved to rise. Yet when she put her name forward for partnership, she was told she was “too aggressive,” “too demanding,” and, most famously, advised to walk, talk, and dress “more femininely.” Wear make-up. Style your hair. Add jewelry. In other words: soften yourself into a version of womanhood that felt palatable to male colleagues.

She refused. And when the partnership door stayed shut, she sued. What came of her case in 1989, Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, was groundbreaking. The Supreme Court ruled that sex stereotyping is a form of discrimination under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. For the first time, the law recognized that punishing a woman for not fitting into a narrow box of femininity is just as unlawful as paying her less for the same work.

That single decision has echoed far beyond Hopkins’s own career. It has been cited thousands of times in courtrooms across the country, and it has become the foundation for cases protecting not only women, but also LGBTQ employees from discrimination. Her courage gave legal weight to the idea that who you are—and how you carry yourself—should never be grounds for denying opportunity.

Even now, the glass ceiling persists, though cracks keep spreading. Women are still measured against impossible standards: be assertive, but not intimidating; be polished, but not vain; be maternal, but not distracted. Hopkins’s case didn’t end those double binds, but it gave generations of women and allies a legal tool and a precedent to push forward.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#41

She died with her camera near her heart, and the world never forgot.

On August 6, 1937, thousands gathered in Paris to mourn a young woman who had seen too much too soon: Gerda Taro, the fearless war photographer who lost her life covering the Spanish Civil War. Just 26 years old, she had thrown herself into the brutal chaos of frontline battle—not as a soldier, but as a witness, armed with nothing but her Leica and an unflinching sense of purpose.

She wasn’t supposed to be there. Women weren’t expected—or permitted—to document war from the trenches. But Taro, with her cropped curls and rebellious spirit, refused to sit behind a desk or wait in safety. Alongside her partner Robert Capa, she captured the raw urgency of Spain’s Republican struggle against fascism. Her photographs told stories that governments wanted buried: the courage of civilians, the agony of dying soldiers, the cost of resistance.

She was crushed by a tank during the Battle of Brunete, an accident in the retreating chaos. But her death was anything but quiet. Gerda Taro became the first female photojournalist killed in action, a martyr for truth-telling under fire. At her funeral, antifascist voices from around the world called her “the first fallen star of journalism.”

She had reinvented herself from a Jewish refugee fleeing Nazi Germany into a daring visual storyteller on the front lines of revolution. She proved a woman didn’t have to pick up a rifle to fight—sometimes a camera was more dangerous.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#42

In 1871, Charles Darwin claimed women were intellectually inferior to men—and wrapped it in the authority of science. Many accepted it without question. But Antoinette Brown Blackwell, a woman already accustomed to breaking barriers, wasn’t about to let that stand.

By 28, she had already become the first woman ordained as a minister in the United States, defying centuries of tradition and theological gatekeeping. She knew firsthand how often “facts” were really just beliefs dressed up to justify excluding women.

So when Darwin published his theory, she took up her pen. In 1875, her book The Sexes Throughout Nature took his arguments apart point by point. She showed that evolution wasn’t a ladder with men at the top—it was a balance built on complementary strengths. She exposed how much of Darwin’s reasoning reflected Victorian gender norms rather than biological truth.

Her critique hit hard. Darwin never mounted a full response. And although her name isn’t as widely known, she opened intellectual doors many thought permanently closed, proving that women weren’t just capable of participating in scientific debate—they were capable of reshaping it.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#43

She arrived in New York with jet-black hair, a name no one recognized, and the determination to become unforgettable. Born Theodosia Goodman in Cincinnati, Ohio, she had grown up far from the glitter and shadows of the stage, but the theater had always called to her. By the time she reached her late twenties—an age when most women were already being passed over in the casting rooms—she was still knocking on doors, still chasing the dream.

In 1914, she was cast as a background extra in The Stain, so far from the camera she might as well have been invisible. But what set her apart wasn’t screen time—it was her precision, her ability to take direction and deliver exactly what was asked of her. That quiet professionalism landed her the lead in A Fool There Was the following year. And with that, the “Vamp” was born.

Now calling herself Theda Bara, she didn’t just step into a role—she became a myth. Studio publicists spun a web of fiction around her: she was no longer a Jewish girl from Ohio, but the child of an Egyptian concubine and a French artist, born under desert stars with powers of seduction and sorcery. Her name, they claimed, was an anagram for “Arab Death.” It was absurd, theatrical, and wildly effective.

She leaned into the fantasy, never breaking character. Photographed draped in veils, coiled with snakes, or framed by skulls, she embodied everything forbidden and fascinating. At a time when women were expected to be soft, silent, and self-effacing, Theda Bara offered a new archetype: dark, commanding, and dangerous.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#44

Beverly Cleary understood girlhood in a way few writers ever have. Through Ramona Quimby, Henry Huggins, and Ralph S. Mouse, she showed generations of girls that it was okay to be bold, emotional, curious, and imperfect. Her stories reflected real childhood — the conflicts, the fears, the tiny triumphs — and made girls feel genuinely seen. With more than 30 books and over 91 million copies sold, her impact shaped how countless young readers understood themselves. Even with her Newbery Medal, Honors, and National Book Award, her greatest legacy is the emotional refuge she built for girls who needed to feel understood. Cleary’s passing at 104 marked the loss of a quiet giant who made girlhood feel important.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#45

She was a woman who learned to read the Earth’s secrets not through sight, but through the tremors that shook its surface. Born in Denmark in 1888, Inge Lehmann had a gift for numbers and a quiet determination that carried her into the male-dominated world of geophysics.

In an era when women in science were often underestimated, she carved her path with precision and patience. While studying seismic waves from earthquakes, she noticed something others had missed—certain shockwaves were behaving differently than expected, bending and bouncing in ways that defied the accepted model of the Earth’s structure.

This subtle anomaly became her key to an extraordinary revelation: the Earth’s core was not a single molten sphere, as scientists believed, but had a solid inner core surrounded by a liquid outer layer. Her 1936 discovery fundamentally reshaped our understanding of the planet, influencing fields from geology to planetary science. She achieved this without fanfare, relying on meticulous analysis rather than bold proclamations, yet her work reverberates to this day, a reminder that persistence and clarity of thought can shift the very ground beneath us.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#46

In 1902, Beryl Markham was born in England, but it was the wild beauty of Kenya that shaped her spirit. She grew up running barefoot with local children, learning to ride horses before she could properly write her name. That same fearlessness carried her into the sky, where she became one of the world’s first female bush pilots, flying over the vast African plains delivering mail, medicine, and sometimes sheer courage.

In 1936, she did what no woman — and few men — had ever dared: she flew solo across the Atlantic from east to west, fighting headwinds and exhaustion, landing in Nova Scotia after a perilous journey that nearly ended in tragedy. Yet, as with much of her life, survival became her triumph.

Her memoir West with the Night is more than an aviation story; it’s a love letter to adventure, to independence, and to a life lived on her own terms. Ernest Hemingway once said her writing made him ashamed of his own — and that’s saying something. Beryl Markham didn’t just chart new skies; she redefined what it meant for a woman to live fearlessly, fully, and unapologetically herself.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#47

In 1991, eleven-year-old Zlata Filipović began keeping a diary in #Sarajevo, Bosnia, never imagining it would one day be compared to Anne Frank’s. At first, her entries were filled with childhood joys—school grades, piano recitals, birthday parties. But when war erupted in 1992, her world shrank to basements, ration lines, and the sound of shells outside her window. She named her diary Mimmy, confiding in it as if it were her best friend, her lifeline to normalcy as her city fell apart.

Zlata’s words captured the horror and heartbreak of the Siege of Sarajevo—neighbors turning on one another, months without electricity, and the small miracles of survival, like finding a candle or hearing a song on the radio. When her diary was published internationally in 1993, it became a voice for children trapped in war zones everywhere.

She eventually escaped to Paris with her family and later studied at Oxford, dedicating her life to humanitarian work and the fight for children’s rights. Zlata’s story is a testament to the power of a young girl’s voice—proof that truth, written in the margins of fear, can outlast the sound of bombs.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#48

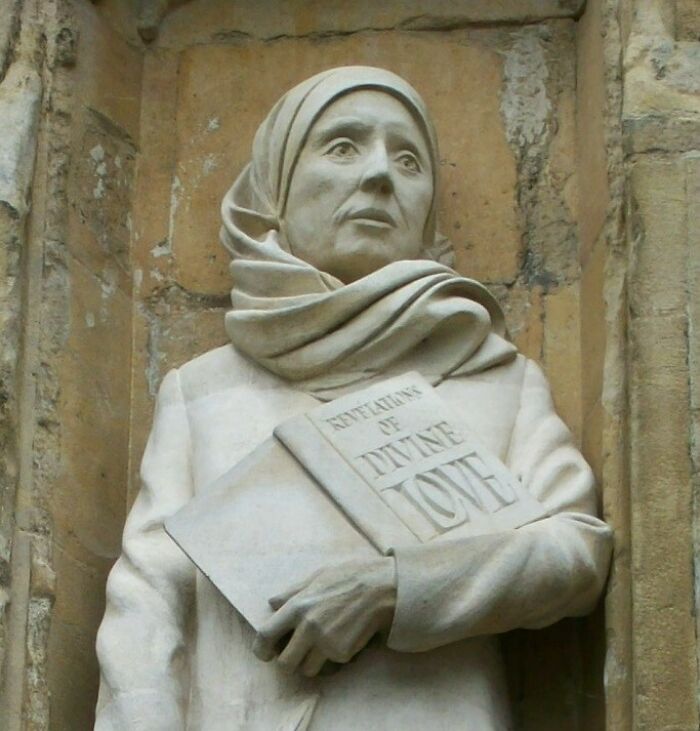

In the 14th century, a time when plague, political unrest, and religious upheaval shook every corner of Europe, a woman in Norwich, England chose to anchor herself—literally and spiritually—in a single, small cell attached to a church wall. Her name was Julian of Norwich. Born in 1342, she would become one of the most remarkable spiritual voices in Christian history, though much about her life remains a mystery. What we do know is that around the age of thirty, while gravely ill and expected to die, she experienced a series of intense visions of Christ. From this profound encounter came her life’s work: Revelations of Divine Love, the first known book written in English by a woman.

Julian lived as an anchoress—someone who withdrew from the world to live in permanent seclusion and prayer. Her cell was part of St. Julian’s Church in Norwich, and it’s from this modest room that she offered spiritual counsel to visitors through a small window, while dedicating her days to contemplation and writing. This choice was radical. In a time when women were denied nearly every form of public authority, Julian claimed a voice not only in religious thought but in authorship itself.

What makes her writings so powerful is not just that she wrote at all—but what she wrote. At a time when the Church emphasized sin, punishment, and fear of hell, Julian wrote instead of love. Not just divine love, but a maternal, tender, and all-embracing love. She described Christ with both masculine and feminine qualities, speaking of God as a nurturing mother. Her most famous line—”All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well”—has echoed across the centuries like a balm.

Julian lived through waves of the Black Death, the Peasants’ Revolt, and the burning of heretics. Yet her theology was not one of judgment, but of trust and compassion. She didn’t deny suffering—she had witnessed plenty of it—but she insisted on hope. Her manuscript was carefully copied and passed from hand to hand, surviving into modern times despite centuries of disregard for female intellect and spirituality.

Image source: womeninworldhistory

#49