Film critics today – especially those that are generally unacquainted with the horror genre at large – love to talk about so-called “elevated horror:” a particularly infuriating term that implies that more mainstream forms of the genre are otherwise beneath their consideration and allows them to smugly justify to themselves the one horror movie every year or so that they deign to speak kindly of. Although these bad faith critics generally just apply the term to any movie made in the 2010s that used minimal jump scares or excessive gore (both of which, it warrants pointing out, are a legitimate tools in the horror filmmaker’s arsenal to shock audiences), it has also been retroactively applied to any movie that time and popularity have deemed “okay” to like by the film intelligencia – movies like Psycho (1960), The Exorcist (1973) and The Shining (1980) – without ever actually considering how transgressive, controversial and generally looked-down-upon these exact same movies were when they were initially loosed onto an unsuspecting public.

As much as I hate the incredibly patronizing and dismissive term, I would be lying if I said that there wasn’t a legitimate distinction between the films that are generally saddled with the term and those that are perpetually denied it. There is a difference between, say, something like Blood Quantum (2020) of even Crimson Peak (2015) and movies like Mother! (2017) or Hereditary (2018), only it’s not necessarily the differences implied when people start throwing around the phrase “elevated horror.” After all, there’s little qualitative difference between any of these movies: all four, in fact, are my absolute favorite horror movies of their respective years. They are all well-crafted, intelligently conceived and burrow under my skin in particularly unsettling ways. It’s just that the latter two have more arthouse sensibilities – are longer, slower paced and more interested in abstraction and metaphor – while the latter two have much more commercial sensibilities – in other words, they want to make money first and foremost and, consequently, generally present more straight-forward stories with a greater emphasis on ghastly set-pieces that play over well with audiences. One isn’t necessarily better than the other, it’s just that they are concerned with radically different things, and a certain strain of “cinema snobs” are more attuned to the one rather than the other.

Near as I have been able to tell, the first film to warrant the “elevated horror” descriptor was Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook. Coming off of a decade or so stretch where horror movies were both coming back in vogue after the 90’s fallow period and decidedly commercial in their approach to the genre, Austrialian filmmaker Jennifer Kent’s directorial debut stood starkly apart from its contemporaries. Its central gimmick (of a dark, expressionistic, storybook monster tormenting a grieving family) ensured that it found a wide audience (most surprisingly of all, within the LGBTQ+ community). At the same time, however, its fixation on monster-as-metaphor, its roots in German Expressionist cinema and its generally restrained approach to shooting meant that critics that would normally turn their noses at the genre found something that they, too, could latch onto. Consequently, it proved to be a rare crossover hit between these two disparate groups of moviegoers, and served as ground zero for emerging trends in both 2010s arthouse-style horror (e.g., The Witch, Us), medical horror (e.g., Midsommar, Relic) and metaphoric horror (e.g., Mother!, It Follows).

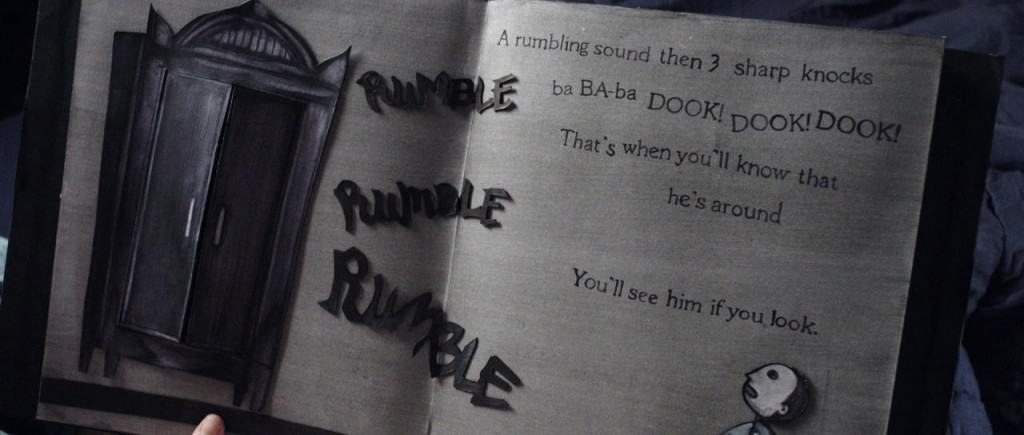

The Babadook follows a single mother (Essie Davis) struggling to manage both her debilitating grief and her rambunctious son Samuel (Noah Wiseman) in the wake of her husband’s death. While reading her son a bedtime story, she finds a sinister, red-and-black book about a creature called “The Babadook,” which shows her being stalked and later possessed by a dark, roughly man-shaped monster in her home, who makes her violently strangle her dog, then her child, then slit her own throat. Only afterwards, she becomes tormented by the Babadook (dook, dook) in her daily life, and finds herself lashing out against her friends and family in increasingly violent ways. And her son, convinced that they are being tormented by the monster from his bedtime story, arms himself against the impending tragedy promised in its pages.

It becomes increasingly clear throughout the film that the Babadook is not a literal creature that’s stalking the family from the shadows of their not-so-picturesque home. He is a metaphor: a manifestation of the mother’s mounting depression in the wake of an unthinkable family tragedy. Misunderstood by her friends and family (who just want her to suddenly “get over” the ongoing trauma that she is struggling with) and abandoned by the basic support network that she should be able to rely upon for help in this moment, the mounting pressures of being a mother, a breadwinner and a widow becomes far too much for her to bear. Her possessions by the Babadook are her inevitably lashing out at those around her when she simply can’t take the strain anymore, and her eventual “defeat” of the monster (letting him live in their basement and feeding him a bowl full of worms every day) is her everyday struggle to manage her depression against impossible odds.

The thing is, though, that the film is equally terrifying whether you view it as a literal haunting from an eccentric, turn-of-the-century monster or as a woman breaking down under the pressures of her everyday life until she becomes something wholly unrecognizable to those that love and depend on her (a thread that was clearly picked up by this years Australian genre entry, Relic). The metaphor, in other words, never gets in the way of the daily terror that the mother both lives with and is possessed by throughout the film, which perhaps explains why The Babadook was so much better received by American audiences than, say, Crimson Peak (which frustrated audiences wanting a good old-fashioned bloodbath) and Mother! (which confused them by filtering the literal horror through so many layers of kaleidoscopic abstraction). Despite its reputation as so-called “elevated horror,” The Babadook sits on the knife’s edge between commercialism and auteurism: deftly balancing between the oftentimes competing needs to frighten us with horrific set-pieces and to guide us through intellectual thought exercises.

Yet, just as Crimson Peak, ahem, gives up the ghost within its opening minutes that “the ghost acts as a metaphor,” The Babadook says the quiet part about its narrative out loud (as part of the very bedtime story that births its titular creature): “there’s no way you’re off the hook if you’re all grown up when you read this book and you snub your nose with a civilized look. You’ll appeal even more to the big Babadook.” Despite being saddled with the weight of the first “elevated horror” film – which wraps around its throat like an albatross around its neck, turning off many blood-and-guts horror fans would doubles appreciate the visceral dread it creates upfront-and-center – The Babadook plays out more like the kind of nightmarish bedtime stories that it draws its dark inspiration from. Jennifer Kent understands that otherworldly and domestic horrors are intrinsically entwined, that they are complimentary terrors that both elucidate and complicate one another. And, here, they are used to continually remarkable effect. In short, The Babadook rejects the taciturn snobbery associated with the phrase “elevated horror,” preferring to scare us good and proper upfront, while giving us something to spectrally linger in our reptilian hindbrains late at night, when we desperately lay ourselves down to sleep in the dark.

Follow Us

Follow Us