Sometimes, you see a movie and you know instantly that it was one for the ages: the second that the lights comes up, the second that you leave the theater, the second you step back into daylight, you just know, deep in the pit of your being, that you have just had a transformative experience. I had that with Blood Quantum (2020), with Us (2019), with Hereditary (2018) and with Mother! (2017), times where you know right away that you’ve seen something really special. Other times, however, movies need to grow on you. Sometimes you walk out, nonplussed, and have the thing slowly burrow down beneath your skin, where it can grow and fester until – weeks, months, even years later – you wake up one day only to realize that you’re obsessed with it (have been, in fact, for some time now).

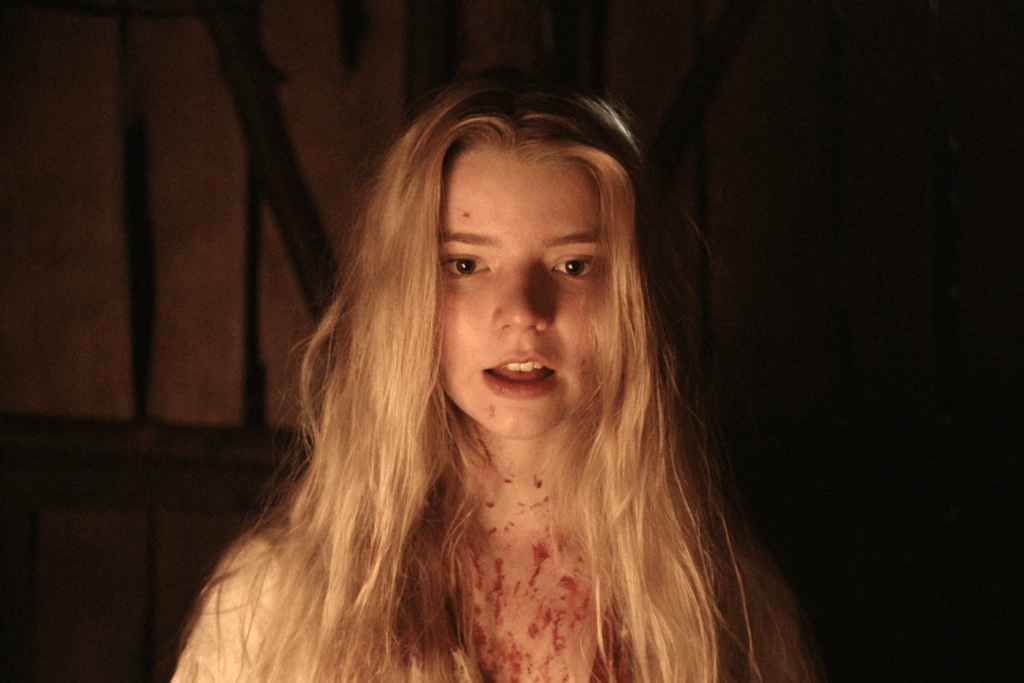

That was my experience with Robert Eggers’s The Witch, which at first left me feeling more than a little underwhelmed despite how handsomely made and authentically rendered the film was. I admired the film’s craft, certainly; Eggers had a clear command of the kind of story he wanted to tell, the cast blended seamlessly into the world he created for them (Anya Taylor-Joy being a particular standout among them) and the dialog was actually pretty spellbinding from the start. It’s just that I didn’t latch onto anything as strongly as I had in movies like, say, Doctor Sleep (2019) or Suspiria (2018) or Get Out (2017). It was a well-made, slow-burn, artisanal horror film – took up a scant 92 minutes of my day – and that was that… or so I thought.

The thing was, though, that I kept revisiting the film over the course of that year. Whether I preferred it or not, I was compelled to compare The Witch to everything else I saw that year, from A Cure for Wellness (2016) to The Neon Demon (2016) to The Void (2016) to The Autopsy of Jane Doe (2016). And whereas other movies oftentimes waned in my estimation of them over time, The Witch looked better and more interesting the more I thought about it. And when I had to decide on a master’s thesis to write, it was inevitably The Witch that stood out as its centerpiece.

Having already left England in order to experience “the pure and faithful dispensation of the gospels and the kingdom of God,” Calvinists William, Kate and their children Thomasin, Caleb, the twins Jonah and Mercy and baby Samuel are now banished from the colonial plantation in which they live as a consequence of the irreconcilable theological differences between them and their neighbors. They trek out into the surrounding wilderness, eventually raising a farm where they can continue to practice their puritanical faith in peace. Samuel, however, is taken by a witch from the nearby woods while in Thomasin’s care. He is slit open, mashed into a paste and spread gorily onto the witch’s naked body, granting the witch the newfound power of flight. And, in Samuel’s absence, the heretofore outwardly functional bonds that tie the family together rapidly begin to collapse: accusing each other of treachery and witchcraft and opening themselves to the temptations of the devil.

Now, I could go on about The Witch from here until Halloween night if I wanted to (and I have a nearly 200 page thesis to prove it). Simply, however, what is so notable about Robert Eggers’s directorial debut is that it generally lets history speak for itself, delving into the historical beliefs, realities and contexts of New England witchcraft as both the text and aesthetic of The Wtich. Characters speak in era-appropriate dialects, spout accurate cultural truism about occultism and generally attempt to recreate actual accounts of colonial witchcraft for its audience. Although it nevertheless holds true that all primary source documents on witchcraft were penned by men (and typically by the men making the accusations against alleged witched), Eggers’s film reframes the content of these persecutorial texts into a lens through witch the character of the witch can be seen as “an evergreen symbol of feminist freedom” by extension (Sollèe 2017, 116). Eggers’s witches are complex characters, coming from oppressive backgrounds, who find power in their schism from the patriarchal family unit and actively direct the courses of their own lives.

While Thomasin is insufferably constrained by the commandments of her faith and family, it is the witch of the wood that kidnaps, kills and converts Samuel into the necessary material components of her sorcery, thus exposing the inherent fragility and toxicity of the family (and, by extension, the patriarchal order under which they live). It is the witch that lures Caleb deeper into the woods – that strips, bewitches and then returns him – which further plunges the family into existential chaos. It is the witches that invade the farm at night, killing Jonah and Mercy and framing Thomasin for the crime, launching her headlong into a conflict that ends in matricide. It is the witches that Thomasin joins in the woods, performing their sabbath and ascending viciously into the heavens. Thus it is the witch, Thomasin, that relays the events of the film to the audience and comes into her own as a woman before them.

Subjected to intense critical scrutiny and scholarship since its release, one of the most fascinating developments in regards to the film is how many writers have (correctly, in my mind) begun to associate Thomasin with the slasher film archetype of the final girl (Borer and Lang 2017; Stanley 2020). Although The Witch could hardly be misconstrued as a slasher film, Thomasin nevertheless meets the criteria for Clover’s female victim-hero over the course of the film. Like more classically conceived final girls, Thomasin “is boyish [… and] not fully feminine” (Clover 1992, 40), evidenced even in her name, a trait shared by fellow classic final girls like “Stevie, Marti, Terry, Laurie, Stretch, Will, Joey, [and] Max” (Clover 1992, 40). She is, like them, chaste, sober, “intelligent, watchful, levelheaded; the first character to sense something amiss [when Samuel disappeared] and the only one to deduce from the accumulating evidence the pattern and the extent of the threat [when she confronted Black Phillip and conscripted with him as a witch]” (Clover 1992, 44). Over the course of the film, which “is so deeply about the powerless” (Subissati and West 2018), we watch Thomasin go from a meek and pious girl to someone who ventures boldly into the forest with her brother, who calls her father out on his innumerable failings as head of household and who fights, to the death, her own mother with, appropriately for a final girl, a phallic melee weapon (in this case, a cleaver). And by the denouement, when she has suffered, endured and, ultimately, triumphed. Drenched in her mother’s blood, standing amidst the carnage wrought upon her family and sluffing off her shift, she gains agency over her own life and brokered that agency into power. She is the last one standing, and now able to reap all the rewards of what that entails.

Another one of the frequently discussed aspects of the film is the various flights taken by the witches of the coven throughout the narrative; this is first done after the red-caped witch of the wood washes in Samuel’s viscera and is later accomplished by the entire coven after they dance at the witch’s sabbath. There is great indexical significance tying witches to flight. However, this supernatural feat has traditionally been accomplished via an enchanted broomstick, a deliberate inversion of “proper” domesticized femininity and another instance of the witch evoking “a ‘hurlyburly’ with its suggestion of misrule and topsyturveydom” (Clark 1980, 129). Like the sorcery performed by Samantha Stephens in the television series Bewitched (1964-1972), this appropriation of “appropriate” female iconography and domestic servitude for magical ends “thus functions as an apt metaphor for feminism – knowledge with the potential for personal empowerment and transformation that is feared and forbidden by the patriarchs” (Sollèe 2017, 113). By this tradition, the radicalized femininity of the witch is constructed in direct opposition to so-called “proper” femininity by transforming the tools of female subservience into weapons against male dominance. While oppositional, it still exists as an easily delineated off-shoot of traditional Western womanhood.

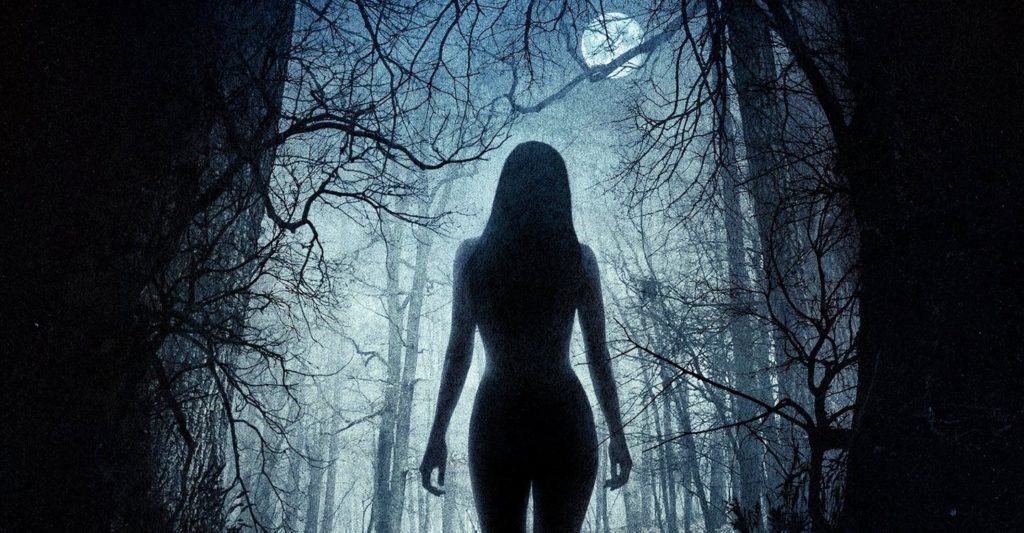

In The Witch, however, no such domestic apparatus is necessary. Through the witches’ own cunning, craft and satanic connections, they are able to propel themselves into the air of their own accord. They are liberated not just from the laws of men, but the laws of God and gravity as well. In a darkly celebratory inversion of centuries of Christian art, mythology and theological constructs like the Great Chain of Being – with God at the head of creation looking down on humanity and, beneath them, on Satan housed in Hell – the film ends with clearly constructed witches, “but they’re also ascending, not descending. They’re not hopping on their broomsticks and flying around everywhere. It is this kind of gorgeously shot ascension” (Subissati and West 2018) that “overturns Christian perceptions of hell/damnation” (Wilson 2020, 173) and counters “even the idea that you have to die to ascend” (Subissati and West 2018). These women are living “deliciously” on Earth, not endlessly toiling in fields and farms and families and wrestling with the Christian anxiety of their unknowable, predestined place in the afterlife.

More so than any other film produced in this current cycle of witch cinema, The Witch directly contends with the long and complex history of witchcraft, gendered oppression and female persecution. Whereas Lar von Trier used Antichrist to shock its audience with the extremities of misogyny and gender-directed violence, Robert Eggers uses The Witch to examine the complex matrices of patriarchal oppression and the various ways that they have historically manifested themselves within Western, specifically American, society. And in The Witch’s subversively ascendant ending, Eggers illustrates a potential path forward that serves as a radical departure from the ways in which that society through the present.

Follow Us

Follow Us