When we think of documentary movies, we typically think of true crime, nature, politics, space explorations, and everything in between. Movies that explore reality date all the way back to the earliest forms of cinema, and have grown in subject matter tenfold through the decades. Although not for everybody, even those who find documentaries boring have to admit that there are some titles that elevate the art form. Although eating popcorn and taking some much due time away from life to have fun is not really compatible with documentaries, non-fiction films are actually very important. But it’s not hard to see why some filmgoers skip nonfiction. I think the main ethical issues that have arisen in the twenty-first century for documentary filmmaking have been the types of popular documentaries that allow an agenda and perhaps a bias start to overtake the entire narrative and message of their films. Michael Moore and Morgan Spurlock are two such examples of filmmakers who are effective at driving home a message but the end result is ripe for dissection from critics who do not agree with their stance. As Patricia Aufderheide points out, “documentary filmmakers have largely depended on individual judgment, guidance from executives, and occasional conversations at film festivals and on listservs.” In some respects, this counteracts the pioneering goals and films from genre icons like Errol Morris and Steve James because contemporary filmmakers seem to execute a film’s narrative to pander to one side or to fill popular demand. But whatever problems recent documentaries may have, the history of documentary film is certainly important as there are countless titles that elevate what it means to be human and exist in the world. Let’s explore why documentaries are important.

Objective Documentaries and Biased Documentaries

Most documentary films explore a subject through interviews, and perhaps the most important aspect a documentary filmmaker needs to uphold is to protect and present their interviewees as objective accounts. I think Mark Achbar and Jennifer Abbot did a good job of striving to maintain a sense of protection for their interview subjects in The Corporation (2003)–a documentary about the rise of business corporations– even though the interviews with the executives went against the narrative angle they were seeking to achieve with the film. On the other hand, Morgan Spurlock has a slanted bias that becomes the defining feature of Super Size Me. Werner Herzog balances both views of Timothy Treadwell in Grizzly Man (2005) to great effect, even though many would likely theorize that Herzog was giving too much screen time to Treadwell’s detractors. It’s a real slippery slope for documentary filmmakers to walk across. In the twenty-first century, these ethical concerns are not really at the forefront of any field except for academia which still requires an analysis based on truths. Documentary filmmakers seem okay with becoming “stars” based on the agenda they explored that has since become sensationalized. I think this is fine with an example like Ross McElwee with what he did with Sherman’s March (1986), but there was a strong strain of this type of documentary filmmaking in the 2000s, but there are also still stellar documentaries that are compelling and not as easily geared towards sensationalism. All artists or personalities can create controversy, but when speaking about documentary filmmakers, I think it is important that any controversies should at least be based on some relation to facts and not so much opinion—but of course, they are also films, and films exist primarily to entertain and engage, therefore, sensationalism could very well be the entire point and a form of art in and of itself.

Well-Made Documentaries Can Reveal Essential Truths About Society

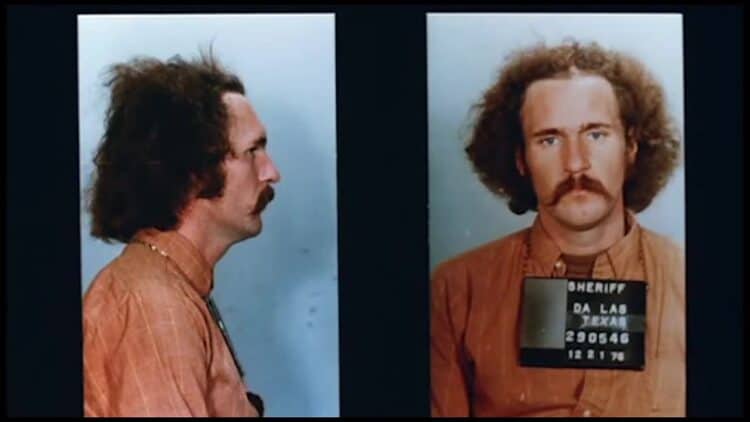

I was glad to finally get around to watching Errol Morris’ immortal classic The Thin Blue Line (1988) since it had been a film that was forever languishing on my must-watch list. The true-crime documentary phenomenon has really taken off in the past few years thanks to Netflix, but it would be remiss to not perhaps think that this film inspired this reenactment-based form of documentary storytelling in some way. While watching the film last night, I was immediately struck by how Morris arranged the interviews in the film. We first hear from Randall Dale Adams who recounts how the events of that evening unfolded from his perspective to how one of the investigating officers tried to pressure him into signing a confession at gunpoint. Then, we start to hear from the officers and their recounting of the events; holes in their argument immediately began to become apparent. Morris’ utilization of the interview aligns with what Leger Grindon referred to as the five contributions to the poetics of the interview: presence, perspective, pictorial context, performance, and polyvalence. Morris uses perspective by eliminating the standard question and answer format by allowing his subjects to speak freely. With this category, the film expands chronologically based on Morris building a narrative that exposes and contradicts some of the conflicting testimonies of all the participants. Presence and pictorial context are also heavily utilized in an intimate framing of the camera Morris. All of his subjects are filmed in an almost film noir type of atmosphere; Adams has direct lighting overhead during his interviews and the officers and witnesses have a more shadowy type of lighting when they speak. Perhaps the biggest category utilized by Morris of Grindon’s argument is pictorial context. The reenactments and clips from various films of the past exist to mock the testimonies of the officials and the witnesses based on Morris’ bias (which turned out to be rightly validated). The reenactments show various angles and different points of view of the circumstances surrounding the shooting. Dramatic effect for realism is also filmed such as the scenes where Adams recounts his and Harris’ visit to the Drive-In Theater and the close-ups of the timelines based on TV Guide entries for television shows. Morris uses performance as more of an innovative aspect of a documentary. The reenactments allow the viewer to see different aspects of the different versions of events related to Robert Woods’ murder. The interviews are more direct, and apart from the three unreliable witnesses, the law enforcement officials, as well as Adams and Harris are presented in a direct talking type of interview to the camera. Polyvalence is also heavily represented in The Thin Blue Line by allowing the interviewees to speak freely and from a range of different points of view. For me, I was convinced of Adams’ innocence about 30 minutes into the film, but Morris allows all of the subjects to speak their truth (or version of the truth) in an organic way that keeps the mystery alive until the closing credits.

It was apparent that while watching the film, Morris was utilizing some pioneering new techniques for the documentary–the reenactments, unfiltered interviews from every side, and the initially puzzling use of old film footage to heighten the drama and atmosphere or to even mock the judge and unreliable, questionable witnesses. A character witness was also interviewed who supplied viewers with additional context of the character of the couple who said they saw Adams in the driver’s seat. Additionally, the defense attorneys fill us in on the record of Dr. James Grigson, letting us know that he has a history of labeling virtually any accused suspect a sociopath beyond redemption. A filmmaker is wise to draw upon the distinctive range of cinematic qualities at work in an interview. Morris certainly fulfills that aspect with this amazing film.

Must-See Documentary: Erroll Morris’ The Thin Blue Line (1988)

The Thin Blue Line is a film that has to be seen to be believed. David Harris has the most interesting arc in the entire film. Apart from outright vilifying Harris, Morris has a lengthy interview with Harris towards the end of the film to not only confirm what we likely already know–he murdered Woods–but also to offer an insight into why Harris ended up the way he did. With this confession of sorts, we are also reminded of how the police department and even the Dallas District Attorney’s office, the judge, the witnesses, and Dr. Grigson was all quick to assign blame to and convict Adams. Morris never gets us any closer to understanding why this occurred, but I think that is not only the eternal mystery with his film but also the overriding mystery of the case in general. Randall Dale Adams is presented as direct, sensical, and passionate in his innocence. There is a point in the film in which somebody claims that Adams is not going to appear to be remorseful because he has nothing to feel remorseful for. The entire accusation against him is a scapegoat of sorts for reasons that remain unknown. It is made even more troubling when you think how this man was literally waiting to be executed…for a crime, he did not commit. What Morris is able to achieve with his subjects is a candid and open conversation that revealed holes in the theories without the participants even knowing that they are revealing the absurdity of the case in their recounting of the events. Yes, Morris does go to great lengths to use filmmaking techniques to reveal absurdity: the female witnesses’ love of old crime shows and movies, the judge’s pompous retelling of grandiose cops and robbers stories—but we as the viewers are aided in our own questions of validity by the cinematic tropes that Morris uses so well. Each participant plays a part in the story, and Morris arranges all of it expertly. It would be hard to claim that this film is the greatest documentary film ever made, but it is certainly the greatest true crime entry.

Follow Us

Follow Us