Similar to Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan (2010) and Darren Aronofsky’s Mother! (2017) – both of which have been discussed at length in previous installments of this horror review series – Lars von Trier’s incendiary Antichrist (2009) has somehow managed to avoid being discussed as a horror film per-se by the general moviegoing public. But whereas Mother! was deemed “too weird” by audiences and Black Swan was deemed “too respectable,” Antichrist falls uneasily in the crosshairs of both: a hard-hitting Cannes release that deeply divided audiences who were varyingly transported, revolted and all-around shocked by the viscerally uncomfortable narrative that transpired over the preceding 108 minutes. And, like Robert Eggers’s The Witch (2016), it is a film with which I am intimately familiar: having analyzed it in-depth for my master’s thesis and used it to track the radical development of witches in film over the past decade. And, yes, despite what it may at first appear to be, Antichrist is absolutely a witch film, although admittedly one that hides its true form under a thick veneer of relationship drama, uniquely European hyper-violence, abstract metaphors and the trappings of high-art.

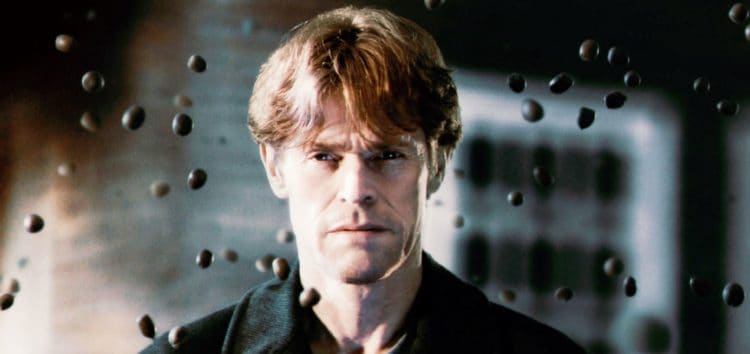

After the tragic death of their infant child, parents He (Willem Dafoe) and She (Charlotte Gainsbourg) struggle with their mounting grief and relational strife. When She grows increasingly inconsolable, He, a psychiatrist, insists on treating her himself despite not being a medical doctor, and becomes convinced that the key to her recovery is rooted in her fear of Eden: their idyllic country cabin and surrounding forest where She spent one last troubled Summer with their son while working on her thesis (a history of women’s persecution entitled Gynocide). But when they arrive, She seems to become increasingly agitated and begins to violently lash out against her dual-role husband / therapist. Her behavior, coupled with a series of distortions in nature in and surrounding their Edenic cabin, soon escalates to the breaking point.

Always known for being something of a provocateur – a feature that would culminate in his infamous expulsion from the Cannes Film Festival in 2011 and his incendiary return to in 2018 – Lars von Trier’s Antichrist catapulted his reputation for producing viscerally challenging films to even greater heights than before. Borne of the same depressive episode that would go on to inspire Melancholia (2011) and Nymphomaniac: Vol. I (2013) and Vol. II (2013), Antichrist was von Trier’s attempt to make a film “for a wider audience, a horror film . . . in the style of [1994’s] The Kingdom [… a] kind of an Antichrist . . . based on the theory that it was not God but Satan who created the world” (Badley 2010, 140). Proving to be his most contentious film to date, the film triggered “involuntary gasps, groans, yelps, laughter, and alleged fainting followed by hooting and booing amid scattered applause” (Badley 2010, 141-142) in its Cannes audience and, elsewhere, “walkouts, vomiting ([in] Toronto), a seizure ([in] New York) […] an unremitting onslaught of polarized reviews [… and] protests and calls for bans in France and Poland” (Badley 2010, 143). Throughout its storied run at and beyond film festivals, reactions to the film ran the critical gamut, from the Chicago Sun Times’ Roger Ebert praising it for its courage in documenting “our fear that evil does exist in the world, that our fellow men are capable of limitless cruelty, and that it might lead, as it does in the film, to the obliteration of human hope” (Ebert 2009, ¶10) to Hollywood Elsewhere’s Jeffrey Wells rebuking it as “an out-and-out disaster” whose dedication “to the late Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky [would quite possibly inspire his] rotted and decomposed body [to claw] its way out of the grave to stalk the earth, find an axe and slay Von Trier in his bed” (Wells 2009, ¶7), although it is perhaps perfectly encapsulated in The Guardian’s Xan Brooks’s review, whose title, delicately poised between impassioned adoration and righteous excoriation, asked “Antichrist: a work of genius or the sickest film in the history of cinema” (Brooks 2009). Thus, Antichrist’s foremost aim, to excite and polarize its audience members by way of their visceral reactions to the violent and violating extremities of its narrative, was easily achieved.

Less a taken-at-face-value chiller and more of a “psychological thriller that evolves into a horror film,” Antichrist intentionally acted as “a glimpse into the dark world of [von Trier’s] imagination: into the nature of [his] fears, into the nature of [his] Antichrist” (Badley 2010, 141). Due to its graphic depictions of violence and sex, the evident anger directed toward traditional institutions of social order (such as the church, the medical profession and the patriarchy as a whole) and the ways in which all three graphically intermingle into the bloody extremities of its climax, the film seems to stem from the same wellspring of cinematic extremism as filmmakers of the so-called New French Extremity, which have been a presence in European horror films since the late 1990s. Indeed, there are many comparisons to be made to films like 2002’s In My Skin (in which a minorly “disfigured” women becomes obsessed with freshly probing her old wounds), 2003’s High Tension (where repressed female sexuality is expressed via a sexually violent, sadomasochistic serial killer) and 2007’s Inside (where a woman who is about to give birth is gruesomely attacked by another woman trying to violently extract her child on Christmas Eve). In much the same fashion as those films did, Antichrist “sees art-house and [horror] converge to mediate on the most horrific aspects of life and what remains after those social veneers are stripped away” (West 2016, 10). Of von Trier’s expansive filmography, Antichrist is the film “that comes closest to a scream” (Romer 2009, ¶32).

Drawing upon the traditions of both “pornography as well as horror,” with graphic close-ups of unsimulated sexual penetration scored against rapturously melancholic opera music, hematospermia (bloody ejaculate) and multiple instances of genital mutilation and disfigurement, Antichrist “produced a sadomasochistic frisson intensified by Gainsbourg’s visceral, taboo-breaking embodiment of aggressive female sexuality” (Badley 2010, 147). In addition, it represented both von Trier’s “return to the dark expressionism” (Badley 2010, 140) and the “oneiric logic, hypnotic expressionism, and technical virtuosity of his earliest films” (Badley 2010, 144) as well as a “blend[ing] his early and late styles and themes and [… breaking them] down into an intricate code” (Badley 2010, 144). Unlike previous von Trier films, “‘horror’ […] offered a range and a vocabulary of understated frissons and excoriating extremes yet is capable of modulating from raw naturalism via the uncanny and the fantastic into surrealism, where all such distinctions might break down” (Badley 2010, 145). The extreme nature of Antichrist, then, is not beside the point of the film so much as it is the point of the film. From its pornographic titillation to its horrific set pieces, the very nature of Antichrist’s overriding narrative and aesthetic palette are deliberately deployed to both express and explore the violence underscoring He and She’s gendered understanding of the world around them and, by extension, our own understanding of it. By employing the conventions of genres as volatile as horror and pornography, Antichrist is able to do so much more acutely and with much greater nuance than any of von Trier’s previous films.

Although we at first are invited to view the film as one of mental derangement and relationship melodrama, as the film transitions from a “psychological thriller […] into a horror film” (Badley 2010, 141), more and more signs begin to appear that clearly demarcate it as a supernatural witch film. : After He and She leave the train, they enter the woods surrounding Eden: an earie, primordial forest wrapped in smoke-like trails of mist and viewed through a swirling distortion in the lens, whereby trees swirl and shift and spin like an illusory eddy. All the while, She becomes for visibly disturbed, more reluctant to move forward and more instinctively resistant to He’s commands to press on toward Eden. Haunted or enchanted woods is strongly evocative of the witches that traditionally dwell there: a dark, all-consuming labyrinth of primitive horrors, a natural sanctum of the supernatural and the place furthest removed from settled, ‘civilized’ land (after all, it is in the woods that Hansel and Gretel meet the witch in her delectable home; it is in the woods that Betty Parris and the other girls of Salem meet with Tituba to hold their communion with the devil; it is in the woods that Suzy Bannion must venture to find the Freiburg Dance Academy in Dario Argento’s film Suspiria). Like the isolated wooded cabin from Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead series (or the Drew Goddard’s parodic The Cabin in the Woods), He and She’s Edenic cabin is instantly recognizable as a witch’s hovel. The various violations of nature – from the three beggars (reminiscent of a witch’s familiars) to the dead chick falling down from the sky (reminiscent of The Witch’s bloody hatchling years later) to the corpse-laden tree on which the couple consummate their relationship – supply us with physical evidence of the profane powers at play in Eden. By the time she crushes her husband’s testicles, shackles him to a whetstone and castrates herself as a form of retributive penance, we understand that the sudden yet seemingly inevitable bursts of violence that we’re seeing are wholly the fault of the husband’s patriarchal hubris (his dismissal of her doctors, his insistence on treating his wife, his bulheaded decision to bring her to Eden and retraumautize her as part of his prescribed therapy).

Emerging at the end of the 2000s, Lars von Trier’s Antichrist bridges the narrative, thematic and aesthetic concerns of the cresting wave of “extreme” European cinema (typified by movies like Xavier Gens’s Frontier(s) in France and Pedro Almodóvar’s The Skin I Live In in Spain) with those of the emergent wave of recontextualized witch films in English-language cinema (typified by movies like Robert Eggers’s The Witch and André Øvredal’s The Autopsy of Jane Doe). By delving into the historical reality of how Christian doctrines were propagandistically coopted in order to legally and morally justify the persecution of witches, Antichrist delivers an unblinking portrait of the modern-day misogyny that directly descended from the European witch hunts. Although certainly not for everyone, Antichrist exists as the genre’s platonic ideal: unflinchingly horrific and viscerally evocative of the multitudinous anxieties that underwrite its characters and narrative.

Follow Us

Follow Us