The fall of the Hollywood studio system in the mid to late 1960s saw an explosive outpouring of creativity, the likes of which had never been seen prior (at least in the US) and have yet to be replicated since. It lead directly to the New Hollywood movement (sometimes referred to as the Hollywood Golden Age), which in turn saw a rise of young, fan-first directors like Steven Spielberg (Jaws), Martin Scorsese (Taxi Driver) and Francis Ford Coppola (The Godfather) and gave a much-needed second-wind to idiosyncratic filmmakers like Stanley Kubrick (2001: A Space Odyssey) that had always been far too eccentric and creatively unwieldly for the safe. Famed schlockmeister Roger Corman (Death Race 2000) launched the careers of many mean and hungry filmmakers, while genre aficionados who would have never survived under contract at “respectable” movie outlets like MGM — people like John Carpenter (Halloween), Wes Craven (Last House on the Left), Tobe Hooper (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre) and George A Romero (Night of the Living Dead) — thrived in this brave new world of grindhouse, drive-in and midnight movies.

One of the most welcome themes running through this New Hollywood was Blaxploitation. Rather than being the cheap, tawdry and racist pictures that many (myself included, at first) often think of them as, they were bold, original and deeply important films that told stories that were both familiar and meaningful to massive, Black audiences that were desperately underserved by the now-defunct studio system. Many represented the first times that Black moviegoers saw versions of themselves on the big screen (or at least versions of themselves that didn’t come part and parcel with a maid uniform) and told fiercely modern, unquestionably urban stories: the kinds of stories that not even more celebrated directors like Coppola and Scorsese were telling with their Irish-American take on American cities. And it gave rise to a great many historic and instantly fascinating characters: magnetic personalities like Youngblood Priest, Foxy Brown and, of course, Shaft.

When it debuted in 1971, Shaft was a film of unprecedented excellence: one that honestly holds up far better in the decades since than the last, flaccid vestiges of the old studio system and its tepid adherents in the changing film industry. John Shaft was a no-nonsense private eye with a shaky (though sometimes amicable) relationship with both the predominantly White NYPD and the decidedly more colorful criminal underbelly of Harlem. He was, in the film’s own words, “the black private dick that’s a sex machine to all the chicks,” someone who “would risk his neck for his brother man” and a complicated man that “no one understands […] but his woman.”

And let me tell you something: the movie didn’t lie. He was basically a Black James Bond: a shoot-from-the-hip, take-no-prisoners, ask-questions-later proto-Luke Cage who could never help but be the coolest cat in the room no matter where he was. Of all the Blaxsploitation movies, and of all the Blaxploitation heroes, Shaft was easily the best of the bunch (and trust me, there was plenty of stiff competition for him to fight off in the years to come). He did the police’s job better than they could, protected his neighborhood from organized crime (both within and without) and stood his ground unflinchingly no matter the odds.

The original spawned a pair of sequels that weren’t quite up to the task of carrying the torch for their title character. A generation later, Samuel L. Jackson starred in a Shaft (2000) all his own, as the nephew of the original Harlem-based P.I. In it, this new Shaft tried to make a go of being a cop — toing the blue line in a way that his storied predecessor never could — but in the end, he was a Shaft. He broke from the force (although the connections that he made while on-duty certainly served him in the private sector) and cracked the case that the regular cops of New York were simply incapable of doing on their own terms.

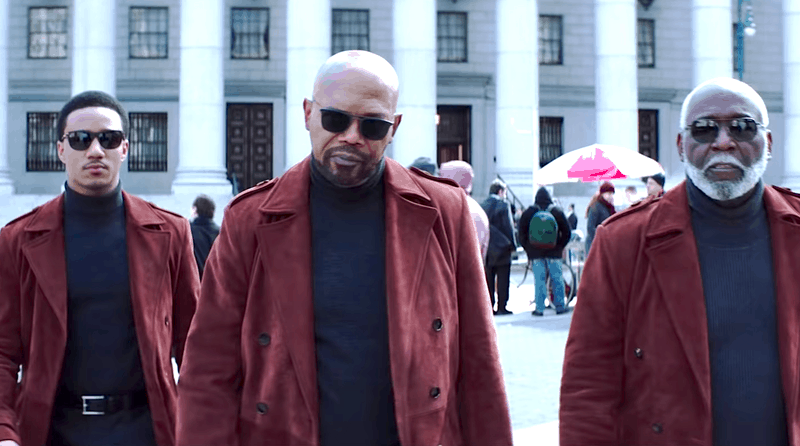

Now, another generation down the line, we have Shaft (2019): same name, different movie. This one follows the littlest Shaft — an FBI data analyst, estranged son of Jackson’s Shaft and grandson to Roundtree’s Shaft (who, it is revealed, had simply been pretending to be Jackson’s Shaft’s Uncle for most of his life). When the heat came down on (Jackson’s) Shaft and his young family in the late eighties, his wife and son left him for their own protection, leaving him to do his Shaft thing all over Harlem before, during and after his 2000-set movie. And young Shaft is more than happy to live a life separate from his grossly inappropriate father (who gave him a box of condoms for Christmas when he was 10 and a box of porn when he left for college). But when an old friend of his dies under mysterious circumstances and he proves to be unmatched to the task of taking on Harlem’s scabrous criminal underbelly, he makes the hard choice of reuniting with his father (and, later, grandfather) in order to mete out justice in the inner city.

At its core, there’s actually a lot of great ideas going on in this movie. Jackson’s Shaft living as an out-of-touch father to Usher’s Millennial sophisticate is rife with potential as a buddy-cop pairing. Shaft II is a street-wise, hard-hitting, blunt instrument who knows the city and its criminals like the back of his hand. Shaft III is a sensitive, tech-savvy and resource-rich upstart who’s able to move in the digital spaces of the twenty-first century in ways that his father never could. Despite their differences, they fall into a complimentary relationship where Jackson can confront criminals directly and Usher can hack databases and set up hidden cameras.

The problem is, however, that the film itself isn’t very interested in balancing out this extrajudicial odd-couple against each other. Either by virtue of director Tim Story’s execution or of screenwriters Kenya Barris and Alex Barnow’s script, most of the film’s rapidfire runtime is devoted to dunking on Usher and “his generation.” The film’s grotesque sexual politics are far worse than any of the shakier stances of earlier Blaxploitation films, which feel even more out of place when you consider that Shaft was never as egregious as many of the other films of its kind that came up throughout the 1970s. Older Shaft is invariably presented as the “correct” way to Shaft, no matter how much stripper-glitter he gets in his beard, and Young Shaft is generally just presented as his I.T. guy, to be dunked on, pushed around and given highly suspect life advice by his father. And the fact that Young Shaft is already an expert marksman and black-belt Capoeira fighter before he teams up with dear-old Dad means that there’s also surprisingly little he can learn from Old Shaft outside of a devil-may-care attitude and fashion. After those reveals, I honestly couldn’t figure out why he didn’t just curb-stomp the low-level drug dealers giving him grief in the first place (the ones that his repeated failure to deal with predicated the father-son team-up in the first place).

The action’s fine. The family reunion is a ton of fun. Even at his advanced age, Roundtree soundly proves himself to be the best Shaft of all. It’s an enjoyable enough romp for anybody who’s seen the first two movies, warts and all. But when push comes to shove, Shaft — this Shaft, the 2019 Shaft — simply isn’t worth the price of admission, especially for fans coming into this franchise for the first time. I think that this seriously has now been well and truly tapped out of all its potential creative juices.

Rating: 2/5

Follow Us

Follow Us